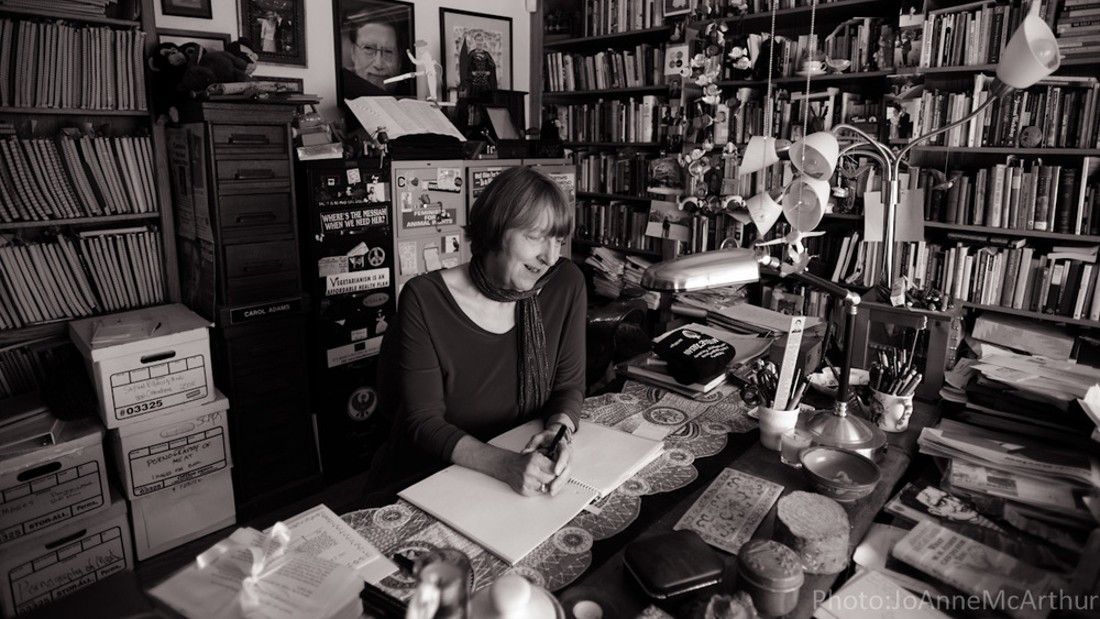

Carol J Adams

Carol J Adams is an American feminist vegan activist and author. Her books include: The Sexual Politics of Meat, The Pornography of Meat and Protest Kitchen, a vegan activist guide and cookbook which she co-authored with Virginia Messina.

She has a Masters of Divinity from Yale University.

Her ground-breaking work in the animal rights movement has been instrumental in making links between our patriachal society and the exploitation and objectification of animals.

Carol became a vegetarian and then vegan when a beloved pony was shot and killed. Later that night, when she went to eat a hamburger, she recognised her hypocrisy and decided to make a change.

As well as advocating for animals, Carol does a lot to help female victims of domestic abuse, having written several books on the subject and starting a helpline for women in the 1970s.

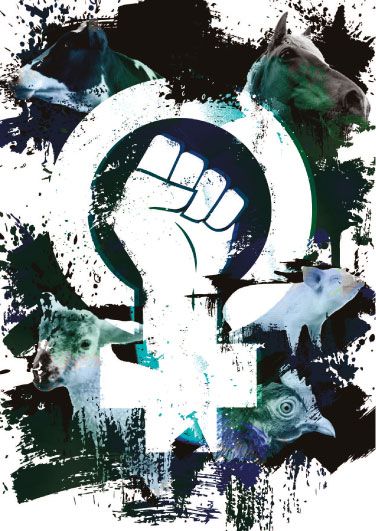

The Sexual Politics of Meat

An interview with author Carol J Adams

There have been many feminist writers over past decades whose work has helped society to understand the pernicious impact of male

There have been many feminist writers over past decades whose work has helped society to understand the pernicious impact of male

dominance while encouraging and enthusing other women (and some men) to demand change. Some of their names are familiar – Alice Walker and Doris Lessing, Margaret Atwood and Germaine Greer. In 1990, one academic and author broadened our understanding by adding a new and previously ignored layer to the feminist story. She was Carol J Adams and her book was The Sexual Politics of Meat.

The way in which it came about was not unusual as many vegetarians and vegans have become so through relating the life of a loved companion animal with what is on their dinner plate. But Carol’s perception went one step further than most, as she explained to Viva!.

“I was already a feminist in the early 70s when a beloved pony was shot and killed. That night, when I went to eat a hamburger, I stopped mid-bite and realised that I was eating a dead animal. I would not eat my pony as she would be buried so why was I eating a cow? I knew I was a hypocrite and had to become vegetarian.

But that self-questioning, I think, sprang out of a feminist consciousness. I began reading biographies of women – suffragettes and feminists – reading novels and history and one day it hit me that there was some kind of connection. I then spent the next 15 years figuring out what it was. The result was The Sexual Politics of Meat.”

Carol J Adams was born in New York state in 1951. From an early age she was influenced by her mother, who was both a feminist and a civil rights activist. Her lawyer father championed environmentalism and was involved in an early lawsuit against the pollution of Lake Erie. You can almost see Carol’s consciousness being formed by her committed parents.

She left her hometown village of Forestville to attend university in Rochester, on the southerly shores of Lake Ontario, where she read English and History but she was also instrumental in bringing women’s study courses to the university’s catalogue. She graduated with a BA in 1972 and obtained a Master of Divinity degree from Yale Divinity School in 1976. She is married to the Rev Dr Bruce Buchanan.

In 1974, Carol moved to Boston to study with Mary Daly, an American radical feminist philosopher, academic, and theologian who described herself as a ‘radical lesbian feminist’. Carol recalls this period as: “… a fascinating time of conversation and mutual critique, my evolving feminist-veganism and her evolving biophilic philosophy (architectural design that links people and buildings more closely with nature) bumping up against each other at times. Usually, at least in the beginning, she had the last word.”

The vegan whirlwind that is now swirling around us may – just may – be changing attitudes but for 40 years, Carol had identified both a feminist perspective on veganism and also a racist one.*

“The problem has been that veganism has been represented in a certain way that skews it from the vast majority of people who are vegans and therefore loses some of these interconnected insights. About 70 per cent of people in the vegan movement are women when the movement is often seen as being led by men. There’s no logical reason why 30 per cent of the vegan community is over-represented in leadership. You have to ask why. They have helped to define the movement as single issue because they’re the ones being listened to. I want to know that the movement I’m part of is pro-choice and recognises reproductive freedom.”

Anyone who has campaigned for veganism knows that men are usually the hardest nuts to crack. That is no coincidence, according to Carol.

“Meat started operating as a way of reinforcing masculinity and male values and their culture protects that. These gender stereotypes prove the sexual politics of meat. People try to disprove them by promoting male vegan bodybuilders and manly male athletes without recognising the context in which that happens. In trying to align with men’s anxiety about manhood and saying ‘no you don’t have to worry, you’ll still be a man if you’re vegan’ it reinforces that. It’s as if manhood is part of a patriarchal world that uses the oppression of animals to maintain itself.

“Every part of the cow’s life, from birth to death, is in a sense a unique oppression”

“Why don’t we deal with male anxiety and say there’s a reason for it; that white men especially are finding out that they don’t rule the world and they don’t have the right to interrupt women. The healthier thing would be to deal with what created the gender dynamics that create this anxiety, not fill them up with reassurances.”

It’s extremely difficult to tie down exactly what the UK spends on meat advertising as there is direct meat promotion and then a hundred other sources – Nando’s, Mcdonalds, KFC etc – and supermarket flyers that arrive almost daily. The figure is huge. Industry spend on dairy alone in the UK is £137 million annually. There is, of course, a feminist perspective on this.

“Meat advertisements are not just using sex, they’re using double entendres. Women are shown stuffing

their mouths with huge pieces of burger or lying under a burger that’s the size of a body, or half a woman, half a burger. There are different ways in which women are humiliated and the double entendres imply that women want to be consumed. It’s a form of hate speech, because the woman is being substituted for the animal or the animal being substituted for the woman. And that’s what’s deadly about it.”

The link between human mothers and female cows is obvious and it is tempting when campaigning to say to women that dairy is rape. A big mistake, according to Carol.

“A feminist insight into ‘Why Vegan?’ is much more complex than that. What happens to cows is a very important part of how we think as feminists but I would never lead with that. Dairy is definitely a feminist issue but I would always put it in the context of a feminist critique of the whole system. We’ve already got a feminist critique of the use of bodies, a feminist critique of the ends justify the means, a feminist critique of violence, a feminist critique of reproduction.

“Within that framework, let’s talk about the cow. Every part of the cow’s life, from birth to death, is in a sense a unique oppression. Separated from her mother, forcibly made pregnant, milked in a way that is so terrible for them, so depleting of their minerals and exhausting their bodies. Often mistreated on the way to the slaughterhouse and then killed. All these are part of the cow’s experience and as vegans we should be talking about the entirety of the cow’s life. Reproductive exploitation is a part of that but it’s not the only part.”

There’s a term from literary criticism called the absent referent and Carol J Adams came to the realisation that animals are absent referents. They disappear as living beings by being killed, they then disappear conceptually because the meat that’s taken from them, the flesh, is renamed to ‘hamburger’ or ‘pork’ or ‘bacon’.

“We use the phrase ‘I was treated like a piece of meat’ when we feel like our will was extinguished. That’s the absent referent, we’ve disappeared from mattering, but by not mattering we become a matter of reference.

Women are also absent referents in a patriarchal society where our will doesn’t matter. We might not disappear through death – although women are killed every day through domestic violence – but women’s will is ignored. Women are often portrayed in very clichéd ways sexually so that who we are as living beings doesn’t matter and are fitted into certain stereotypes – and become absent referents.”

I know that in our early years, Viva! frequently used the word ‘veggie’, even though we meant vegan and it was done so people would, we thought, more readily identify with it. We were not on our own it seems.

“In 1990, vegan wasn’t a common term and even in 2000, when I wanted to call something vegan, my publisher said that no one would recognise it. That has changed but with the good comes the bad. You look up ‘vegan women’ on Google and you get sexy vegan women. This is not progress, this is not how vegan women should have to be defined. It misses the whole plurality of veganism and excludes vegans who might have cancer or acne or a colostomy bag.

“Single issue veganism, as it’s come to be expressed, is dangerous because it mischaracterises veganism as being about health when it has always been about ethics. We should be talking about healthy ethics and not body size or appearance.”

I know that many vegans struggle to understand how a woman who calls herself a feminist can still eat meat and dairy. They are not on their own as Carol J Adams thinks similarly – but with a very big caveat.

“I can’t be a feminist and still consume meat and dairy and that’s why I’m vegan. However, I would never pose that to another feminist. It’s taking something that should be about consciousness changing and making it a rule. As feminists we have been trying to redefine how rules work so, to enter a conversation by saying ‘you can’t be a feminist and still eat meat and dairy’ would completely violate the spirit of feminism.

You look up ‘vegan women’ on Google and you get sexy vegan women. This is not progress, this is not how vegan women should have to be defined.

“I have staked my whole writing career on that argument and would like to see it made not in a confrontational way but as invitational – ‘this is why it matters, this is why it works, this is why I’m at peace, let me share some food with you’, rather than: drawing a line in the sand.”