12 Farming Myths Busted

This is part three of four in this section. Read part one and two:

1. The shift to plant-based protein production will put most UK farmers out of business

Farmers for Stock-Free Farming lays out a clear, three-pronged approach that outlines a just transition for all farmers: Growing crops for human consumption; Farming carbon capture through rewilding grazing land; and Diversifying into non-traditional agricultural activities such as those related to tourism, retail initiatives, or renewable energy.

One crofter, in Sutherland, Scotland, has engaged all three of these approaches! On her 80-acre croft, deemed suitable only for grazing cattle and sheep, Gina Bates has planted an orchard of 312 hardy, hybrid, hazelnut trees from which she expects to harvest around 12 kilos of nuts per tree in 3-4 years’ time. Most of her croft, which was formerly used to graze cattle, is being left to rewild and Gina is already seeing a new abundance of flora and fauna. Meanwhile, she is building the first of several glamping pods so that she can supplement her income with tourism.

Clearly, Government support is needed to help farmers and crofters to make these shifts. Research funded by the Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures suggests that public funding is only part of the solution. They propose that private individuals and businesses could buy carbon credits, in the form of tree-planting, to offset their carbon footprints and thereby provide an alternative source of income to farmers and landowners.

2. We need to graze cattle and sheep to turn grassland into food

This is a completely unnecessary use of grassland. A 2019 study from Harvard Law School showed that if we use all current UK cropland to grow food for human consumption, we can more than feed our entire population. And, yes, that includes enough protein too. There is simply no need to make food from grassland. Instead, it can be rewilded and given back to nature.

3. Grassland is an important carbon sink and we should leave it alone

A carbon sink refers to the net annual removal of carbon from the atmosphere. Pete Smith, Professor of Soils and Global Change at Aberdeen University, and the director of the Scottish Climate Exchange Centre for Expertise, stated in his 2014 analysis that, “Simply having grassland does not result in a carbon sink…” Grassland is not a magical climate change champ. Most grassland in the UK exists because humans chopped down trees. Returning grassland to native woodland would be the ultimate way to sequester carbon and meet our climate change goals.

4. Grazing ruminants help soil-carbon sequestration which offsets any greenhouse gases the animals themselves produce.

A 2017 study by the Food Climate Research Network addressed the question of the net greenhouse gas balance of ruminant grazing. Experts in soil science, animal science, life cycle assessment, ecology, conservation and biodiversity from around the world (including Oxford, Cambridge and Aberdeen universities) studied this question for two years. Their conclusion was: “The contribution of grazing ruminants to soil carbon sequestration is small, time-limited, reversible and substantially outweighed by the greenhouse gas emissions they generate.”

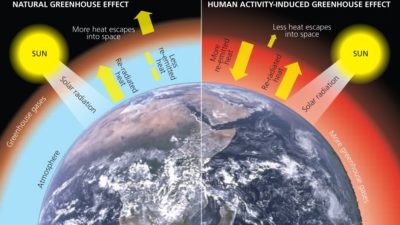

5. Methane is a short-lived greenhouse gas and therefore not a serious contributor to climate change

The power of a greenhouse gas to heat up the atmosphere is measured in terms of its Global Warming Potential (GWP); typically over a 20-year or 100-year time period. The GWP of a greenhouse gas is a function of two properties: how effective the gas is at trapping heat whilst it’s in the atmosphere, and how long it stays in the atmosphere before it breaks down. Even though methane only persists in the atmosphere for around 12 years, it still traps 72 times (GWP 72) more heat in the atmosphere than CO₂ over a 20 year time period. In other words, methane is a very potent greenhouse gas.

Globally, 44% of methane comes from livestock agriculture (including fish farming). In a year, the methane produced by a single dairy cow equates to the greenhouse gases produced by a mid-sized car driving 20,000 kilometres! As long as we continue to farm animals, methane will continue to exert its damaging warming effects on the planet.

6. Grass-fed beef is better for the environment than grain-fed, feedlot cattle

Not true. Aside from the massive destruction of habitat to provide grazing land for livestock, grass-fed cattle produce up to four times more methane than grain-fed cattle. This is due to the fact that grass is harder to digest than grain and also because pasture-fed animals take longer to reach market weight, so more time to poop and belch! Even taking into consideration all the grain that is grown and fed to livestock, grass-fed beef still requires more land than grain-fed per unit of beef produced. Even if it were true, there simply isn’t enough land for everyone to eat grass-fed beef anyway. All told, grass-feeding livestock is a very inefficient, wasteful and environmentally costly way to produce food.

7. Buying locally sourced meat and dairy is more environmentally friendly than a vegan diet that relies heavily on imports

Here we have two myths in one! The whole ‘locavore’ scene has recently undergone a revival. Covid-19 limitations, our departure from the European Union, and the escalating climate crisis have all contributed to the current obsession with local food.

In terms of carbon footprint, and according to Our World in Data, eating local is one of the “most misguided pieces of advice.” For most food products, greenhouse gas emissions from transportation form just a fraction of the total carbon footprint. Most emissions occur on the farm and from land-use change. It’s what we eat that matters, not where it is from.

For example, for the beef supply chain, transport accounts for just 0.5% of total emissions. Even for a product such as avocados, which have a reputation for being environmental hard-hitters, transporting them from Mexico to the UK still only comprises around 8% of their total carbon footprint.

For certain foods, eating locally can mean higher emissions than consuming their imported counterparts. Importing lettuces from Spain during the winter months, for example, incurs three to eight times lower emissions than growing them locally in heated greenhouses.

Concerning the myth that a vegan diet necessitates a heavy reliance on imports, please read our section on “Growing Crops for Human Consumption” to see the wide variety of crops that can be grown in the UK, including a surprising selection of protein crops. We really have no need to look beyond our own fertile and temperate part of the world to eat a healthy, balanced, vegan diet.

8. We don’t need to change what we eat; we just need to stop wasting food

Another myth propagated by those unwilling to change their diets. In their paper entitled: The opportunity cost of animal-based diets exceeds all food losses, the authors show that by replacing all animal products in the US with crops grown for human consumption (of the same approximate nutritional and calorific value), an additional 350 million people could be fed! This was significantly more than the number that could be fed by eliminating all food supply chain losses (waste) in the traditional diet.

9. As long as I buy organically farmed meat/dairy/eggs I am not harming the environment

A study by Clark and Tilman (2017) looked at 742 agricultural systems across five environmental factors: greenhouse gas emissions; land use; fossil fuel energy use; eutrophication potential; and acidification potential. The results were surprising. They found that although organic systems use 15% less energy than conventional systems, organic systems require more land, have a higher eutrophication potential (which, amongst other things, leads to aquatic dead zones), and emit similar greenhouse gases to conventional systems. Certainly, although organically farmed animals might have better feed, some access to the outdoors, and less intrusive husbandry, they still meet the same gruesome and untimely end.

10. We need some grazing ruminants in order to stimulate a diverse range of habitats and biodiversity

This is a myth that is sadly promoted even by some vegans. Ruminants do recycle nutrients, excreting them in their poo, which can make them more readily absorbable to plants. However, the disadvantages (which we have discussed fully in earlier sections) far outweigh any benefits. Ruminant meat has adverse environmental impacts approximately 100 times those of plant-based foods. Sheep are particularly problematic. Domesticated and imported from ancient Mesopotamia a few thousand years ago, sheep did not evolve with our ecosystem and have the tendency to eat just about everything in sight!

When Gina Bates first purchased her 80-acre Sutherland croft, the ground was severely poached and muddy due to the previous owner’s dozen or so cows. In certain areas, the grass was completed gone, replaced by heavy, water-logged mud. Three years later, the terrain has restored itself and is teaming with an abundance of flora and fauna. Gina reports that she now sees more wild grazers; both roe and sika deer.

Our vision for the UK is one of a restored ecosystem where wild grazers replace farmed animals, and boar, beaver and lynx once again take their place in a balanced ecosystem. This process will take time. Farmed animals will not disappear overnight so, until that time, if you are desperate for a few cows, rescue some and allow them to live out their natural lives on your land in peace. And let’s work towards ensuring the wild ancestors of farmed animals are kept safe in their natural habitats.

11. Crops can’t be grown without farmyard manure or artificial fertilisers

Several growers across the UK have proved this wrong. Tolhurst Organic Farm in south Oxfordshire is a veganic farm – no artificial fertilisers and no animal products. Ian Tolhurst employs a seven-year rotation to keep his soil healthy including two years of green manure crops (legumes, such as lucerne and various clovers) and a further over-wintering of green manure. His 17 acres supply 400 families for 51 weeks of the year with 75 per cent of their vegetable needs.

The Artisan Grower in Aberdeenshire, also veganic, amends their soil throughout the season with alalfa, rock dust (minerals come from rocks!), and seaweed! Seaweed was the traditional fertiliser used by crofters on the western isles to fertilise their crops. The kelp industry is undergoing a revival, so seaweed could once again become a key source of fertiliser.

Bridgefoot Organic Co-op, also in Aberdeenshire, supply a range of fruit and vegetables to 200 customers a week, year-round. They use a humus builder made from red clover, chicory, cox foot and ryegrass to enrich their 7.5 acres.

12. Seeing the fields full of sheep is a natural part of our landscape; it’s an important part of our culture and tradition

Pasture is widespread in Britain because our forebears cut down all the trees! Our “natural” indigenous vegetation is native forest. Sadly, only around 2% of Britain’s ancient forests remain.

Sheep, as already mentioned, were an import. In fact, in both England and Scotland, the mass influx of sheep formed a painful part of our history. In England, the greed of landowners in acquiring large numbers of sheep led to the illegal enclosure of what had been common grazing land, causing many villagers to lose their ability to survive, and whole villages to disappear.

In Scotland, a similar occurrence led to the tragedy of the Highland clearances. Landowners wanted the land for sheep and forced their tenants out of their homes. The legacy of the clearances can be seen in the deserted and ruined villages all over the Highlands.

So, sheep are by no means a part of our cultural tradition, no more than green fields are a part of our natural heritage.

The growing of crops was much more prevalent prior to the explosion of livestock. Even in the Highlands and Islands, crops such as barley, oats, and potatoes were cultivated widely and harvested by hand. Hemp was a staple crop grown all over the UK from 1000 AD and used for food, clothing, fuel, and shelter.

Our ancestors would never have dreamed of growing food to feed to livestock! They ate over 800 varieties of fruits and vegetables and very little, if any, meat. Animal products were for the wealthy who, coincidently, had ‘exotic’ illnesses such as cancer, arthritis, diabetes and gout. Up to the early 20th century, heart disease was not even included in medical textbooks.

We have become lazy and unhealthy. Just seven crops are grown on 91 per cent of UK cropland and they are crops that are mostly fed to livestock.

Going back to our roots means just that: using our cropland to grow food for human consumption and giving the rest back to Mother Nature.

See our “Revisioning Britain” map for an idea of how this might look.