Climate Crisis

Foreword by Brendan Montague, Editor, The Ecologist

We need to reinvent luxury. We need a better understanding of high quality. We need to treat ourselves, but treat ourselves well. Or to rediscover. The ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus was a hedonist, and spent a considerable amount of time pondering what made for a good life. When it came to food, he advised only bread and water which, he argued, always tasted sublime to a person experiencing real hunger.

For hundreds of years meat has occupied the territory of luxury. The old kings of England used the country as a hunting ground and paintings of the era show feasts resplendent with dead animals. Indeed, the foundation myth of our origins as humans is that we were apes rolling around in the forest undergrowth eating leaves until the desertification of the Savanna. Then we became man, upstanding, a hunter, an eater of meat. There is actually no evidence to support this, the prevailing hypothesis about what makes us human. And yet, if it is true, what does it tell us about ourselves? That we are a contented beast, a great animal surrounded by an abundance of food. The African forest contained all the wealth we early humans could possibly need – it was this environment rich in foods including plant proteins that allowed us to develop such a powerful mind. The transition to meat was in fact the act of desperation. The effective suckling of goats and cows in this story does not seem luxurious but really quite grim. The bleeding of cattle, and eventually the slaughtering of our fellow living creatures seems utterly dreadful. Yet this is the myth that is supposed to make eating meat a natural part of who we are.

So what does this mean for us today? I think we need to evoke the deep emotional relationship we have with food in order to influence behaviours towards what is healthy for us as human beings and also what is sustainable for our planet. We need to celebrate plant food, and build customs and myths that place the beetroot and the potato at the centre of our celebrations, of our identities. Luxury, when one really digs into its meaning, is simply that which is not affordable to everyone. We show off by eating meat. But meat is cheap, and dirty, and everywhere. Real luxury is organic foods, locally sourced foods, home grown foods, plant based food. These foods need to be rich with stories – grown by those we love, only for us, over time and with great care. Meat in turn needs to be treated with disgust. As a journalist, I have seen the new mega farms spreading into British agriculture like mould. The cows are chained, clearly in pain, barely able to suffer the weight of their bloated udders. Thousands of them. Living within the rivers of slurry they produce. It’s not luxury, it is despair, and it is disgusting.

The publication of this second edition of the Envirocidal report could not be more timely. Sir David Attenborough has finally taken the message to middle England that climate change is an existential threat. The inspiring and innovative manifestation of Extinction Rebellion, with more than a thousand people willing to be arrested peacefully protesting in London, and the direct actions simultaneously taking place in cities around the world, show that people of all ages are determined to act on climate change – and also biodiversity loss. Veganism is becoming the new normal. I became vegan this year after holding a vote of readers of The Ecologist asking whether its editor could have a pescatarian diet without some level of hypocrisy. The answer was resounding. And as this report makes clear, eating fish and foregoing other meat is not sufficient if we want to significantly reduce our personal climate impacts – and lead in our communities and in our countries on carbon reduction.

This report is most valuable because it provides a comprehensive review of the current scientific literature. While it is an appeal to emotion and identity that will influence behaviour, we really do need to be confident about our claims before we go into the world making demands of other people. We need to be clear about the rational arguments, as well as the emotional appeal. This report sets out beyond reasonable doubt that continuing to eat meat is irrational, and dangerous. It reveals exactly how livestock farming is linked to all the main areas of concern including global warming and climate change, land and water use, overfishing, biodiversity loss, deforestation, desertification, air pollution, antibiotic resistance, world hunger and food waste.

Those of us who are already committed to environmentalism now have to face up to the fact that the vegan diet (perhaps peppered with the occasional supplement) is the only truly green diet. The best solution to the compound crises of climate, biodiversity, soil depletion is to simply stop eating animals. A global switch to diets that rely less on meat, fish, dairy and eggs and more on fruit and vegetables could make a huge difference to us and future generations.

I am also encouraged that this report talks about government action. We can only do so much as individuals and fundamental change will come only through changes in how we eat, how we farm, how we produce at a national and international level. We need to lobby, transform and replace many of the institutions that form our civil society. Our schools can no longer have any ethical authority while serving meat based meals to our children. Our hospitals cannot serve meat that, in time, will make patients sick. The government needs the Green Pea Marketing Board, sending free food into our schools just as when I was young we were given free milk. But ultimately, we need to change our feelings about food. Plants are healthy, rich, plentiful and tasty – they are luxurious. Spice is very obviously the spice of life. Animals bring us tremendous joy especially as companion animals – but the idea that they should be minced and ground down to form part of our diets is macabre and grotesque.

This report explains the many benefits of moving to a plant-based diet. But this is not about sacrificing meat, it’s about discovering that we can and must do so much better.

Brendan Montague, Editor, The Ecologist

Summary

Global warming isn’t a prediction, it’s happening around us right now and livestock farming lies at the heart of it.

It has happened naturally, millions of years ago, but this time it’s man-made. Greenhouse gas emissions from animal agriculture come from enteric fermentation (cows burping and farting methane), gases from animal manure (methane again), deforestation for grazing land and soya-feed production, soil carbon loss in grazing lands, energy used in growing animal feed, processing and transporting animal feed and meat and nitrous oxide releases from nitrogenous fertilisers – all contribute to the production of gases responsible for global warming.

Governments have joined together to try to limit global temperature rise to less than 2°C, or ideally 1.5°C, above pre-industrial levels – a critical threshold above which scientists believe it would have devastating effects.

We’re not doing very well – we have already broken through the 1°C barrier as the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere reached an all-time high. So, we are now already halfway to the 2°C and very close to reaching 1.5°C. If we are going to avert an environmental disaster, we must take urgent action.

Some experts warn that current trends could lead to a 4-5°C increase in global temperatures by the end of this century. If the warnings are ignored, human-induced climate change will lead to a whole new range of health risks, the like of which we have never seen before: polar ice melting, rising sea levels, flooding, drought, water shortages, loss of biodiversity, mass extinctions, hurricanes, tornadoes, starvation, infectious disease outbreaks, conflict and warfare.

This may sound like science fiction but some scientists say if we don’t act soon to curb climate change, we could be heading towards a situation resembling the world ravaged by drought and hardship seen in the futuristic film Mad Max: Fury Road.

As food production expands to meet the world’s growing appetite for meat, emissions from livestock farming continue to rise. The only way to stop this is to change the way we eat, drastically reducing animal food production. Simply using energy-efficient light bulbs or switching to an electric car will make little difference if you continue tucking into steak and eating burgers.

Our oceans are being decimated, ancient coral reefs destroyed and marine ecosystems are collapsing as industrial bottom-trawlers plough through sea beds with no consideration of the consequences. This is unprecedented in the history of animal life and may disrupt ecosystems for millions of years to come.

Three-quarters of the world’s food comes from just 12 plants and five animal species. Massive livestock populations have profound consequences for biodiversity due to deforestation, change of land use, overgrazing, degradation of grasslands and desertification. Loss of habitats and species extinction are taking place at an alarming rate. Human activity has pushed us into the sixth mass extinction and natural ecosystems are degrading at an unprecedented rate.

Deforestation remains alarmingly high in many parts of the world. Part of the problem is food imports – it may look like we are improving matters on our own doorstep but really the problem is just being moved elsewhere. This is known as ‘carbon leakage’ and of course, it does not reduce global emissions.

Desertification and land degradation are being driven by the expansion of livestock farming and the production of animal food. Drastic action is required immediately if we are to attempt to halt and reverse it.

The alarming rise in antibiotic-resistant superbugs is a problem of our own making, a direct consequence of the inappropriate use of antibiotics in livestock farming. Many farmers routinely use antibiotics to promote growth and prevent disease in healthy animals. In some countries, the vast majority of antibiotics is used in this way.

Most people assume that industry and traffic are the main causes of air pollution. However, agriculture is the single biggest cause in Europe, contributing more than residential energy use or power generation. Reducing air pollution could mean the difference between life and death for millions of people every year.

One in nine people in the world today are undernourished yet we feed a third of all crops to animals. Growing food for human consumption, without first feeding it to animals, could nourish an additional four billion people – more than enough for everyone for years to come! We all know how wasteful old gas-guzzling cars are – how long before livestock farming is viewed the same way?

Animal foods require far more precious water than most plant foods. Half a billion people in the world face severe water scarcity all year round. We have already seen how severe drought contributed to the conflict in Syria. There is a direct path leading from climate change to drought, agricultural collapse, mass human migration and conflict. It looks like Yemen may be the first country to actually run out of water. Which countries will follow? Pakistan, Iran, Mexico or Saudi Arabia? Will future conflicts be fought over water rather than oil? Scientists believe so.

A shift towards a plant-based diet would help preserve water and reduce global hunger and malnutrition. We may have a global economy, but the huge disparities between rich and poor, and the persistent depletion of environmental resources used in food production on land and at sea, prevent us from reducing the very basic public-health problem of world hunger. On top of this, we throw a huge amount of food away! If food waste were a country, it would be the third-largest emitting country in the world. In the UK, the average family throws away £700 worth of food a year.

The global demand for animal foods will continue to rise unless governments actively promote a change of diet. There is a clear need for a strategic, integrated approach to agriculture, forestry and other policies linked to how we use the planet’s natural resources.

The best solution is to stop eating animals. A global switch to diets that rely less on meat and more on fruit and vegetables could save eight million lives by 2050 and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by two thirds. We talk the talk with sustainable energy and electric cars – let’s walk the walk with diet!

Global warming is happening around us right now. It’s happened before, millions of years ago, when a burst of carbon dioxide raised Earth’s temperature by 8°C. It had major impacts on plants and wildlife and took 200,000 years for the planet to recover.

This time it’s caused by human activity and livestock farming lies at the heart of it. Large volumes of greenhouses gases are being released into the atmosphere, from the huge numbers of livestock around the world, from manure, fertilisers, deforestation and from fossil fuel energy used by the meat and dairy industries. This is how livestock farming is driving the climate crisis. If we are going to avert an environmental disaster, we have to take urgent action drastically reducing animal food consumption. A global switch to a vegan diet could save eight million lives by 2050 and reduce food-related greenhouse gas emissions by two thirds. Using energy efficient light bulbs or switching to an electric car just won’t cut it if you continue tucking into steak and eating burgers.

“Global warming isn’t a prediction. It is happening.” James Hansen – former NASA Scientist.

According to scientists, we have now entered a new geological period in history, the Anthropocene epoch, where human activities are directly responsible for global environmental changes.1Steffen W, Crutzen J and McNeill JR. 2007. The Anthropocene: are humans now overwhelming the great forces of Nature? Ambio. 236 (8) 614-621.

Animal agriculture lies at the heart of the problem; greenhouse gases come from huge numbers of cows burping and farting methane (enteric fermentation), from manure (methane again) and carbon dioxide from mass deforestation making way for grazing land and animal feed production. Energy from fossil fuels is used to grow, process and transport animal feed and meat, while nitrous oxide is released from fertilisers used to grow animal feed. This is how animal agriculture is driving the climate crisis.

Governments, and the United Nations, have joined together to try and limit global temperature rise to less than 2°C, ideally, 1.5°C, above pre-industrial levels – a critical threshold above which scientists say would take us into unchartered territory.

We’re already dangerously close having exceeded 1°C emissions above pre-industrial levels in 2015. Current trends could lead us to a 5°C increase by the end of this century. If ignored the crisis will lead to polar ice melting, rising sea levels, flooding, drought, water shortages, loss of wildlife, mass extinctions, hurricanes, tornadoes, starvation, infectious disease outbreaks, conflict and warfare. We are already seeing some of these effects.

If we are going to avert an environmental disaster, we have to take urgent action and drastically reduce our consumption of animal foods. A global switch to a vegan diet now could save millions of lives by 2050 reducing greenhouse gas emissions substantially. Using energy-efficient light bulbs, or switching to an electric car, just won’t cut it if you continue tucking into steak and eating burgers.

What is global warming?

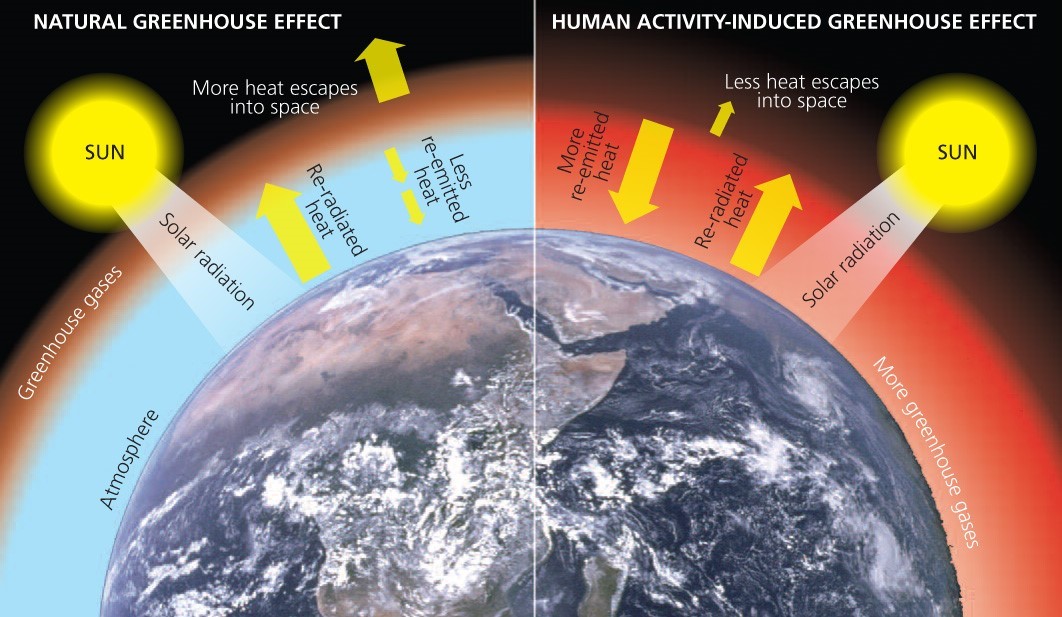

The term ‘global warming’ refers to the rising temperature of Earth’s climate system caused by greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide. It’s also known as climate change or the climate crisis.

The Earth’s atmosphere acts as a protective layer, letting sunlight in and retaining heat. The gases in the atmosphere act a bit like the glass walls of a greenhouse, trapping the sun’s heat and stopping it from escaping back into space. Think of greenhouse gases like throwing an extra blanket on the bed, then another one, then another one! Many of these gases occur naturally, but human activity is increasing the concentrations of them in the atmosphere.

All activities involving the combustion of fossil fuels contribute; electricity generation, heating, transport, industry and agriculture – including livestock farming. Human activity is adding enormous amounts of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, increasing the greenhouse effect leading to global warming.

Greenhouse gases

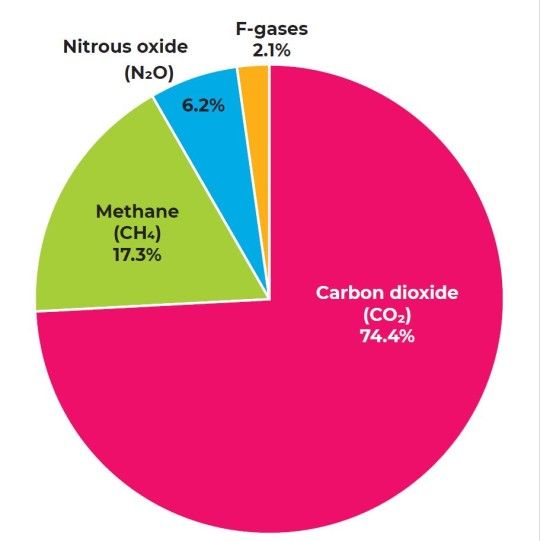

The largest contributor to global warming is carbon dioxide. Other greenhouse gases are emitted in smaller quantities, but trap heat far more effectively and can be many times stronger.

The main three greenhouse gases are:

- carbon dioxide (CO2)

- methane (CH4)

- nitrous oxide (N2O)

In 2016, carbon dioxide contributed around three-quarters (74.4%) of all greenhouse gases, methane contributed 17.3%, nitrous oxide, 6.2% and fluorinated (F) gases made up the remaining 2.1%.2Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/greenhouse-gas-emissions This is a slight shift compared to 2010 levels with a small reduction in carbon dioxide and a small increase in methane, possibly reflecting the move to more sustainable energy sources but no such move to reduce livestock numbers – the major driver of methane levels.

GLOBAL GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS BY GAS (2016)

Carbon dioxide (CO2)

Carbon dioxide is the greenhouse gas most commonly produced by human activity. Fossil fuel burning and industrial processes are the main sources, responsible for 65% of all anthropogenic (caused by human activity) greenhouse gas emissions.2IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, RK Pachauri and LA Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/

Carbon dioxide emissions can also be attributed to deforestation, land clearing for agriculture and degradation of soils.3EPA. 2017. Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-data In other words, chopping down trees increases the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. During the natural process of photosynthesis, trees remove (sequester) carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to build carbohydrates that are used in their physical structure, they release oxygen back into the atmosphere. When land is cleared, there are fewer trees to sequester carbon from the atmosphere, and if trees are burned or left to rot, additional carbon is released into the atmosphere. This type of activity accounts for around 11% of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.2IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, RK Pachauri and LA Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/

The level of carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere is now 40% higher than it was when industrialisation began in the late 19th century.4European Commission. 2017. Climate action, Causes of climate change. https://ec.europa.eu/clima/change/causes_en

Methane (CH4)

Agriculture is the main contributor of methane, which is responsible for 16% of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.2IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, RK Pachauri and LA Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/ The large volume of emissions from ruminants (cows, goats, sheep, giraffes, yaks, deer and antelope) comes mainly in the form of methane from enteric fermentation.5Carlsson-Kanyama A and González AD. 2009. Potential contributions of food consumption patterns to climate change. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 89 (5) 1704S-1709S.

Ruminants have a specialised stomach called a rumen in which tough plant fibres called cellulose and complex carbohydrates are digested or broken down by bacteria into simple molecules that the animal can absorb into their bloodstream. This is called enteric fermentation and it produces substantial amounts of methane in the form of burps and farts! Cows produce the most methane, so because of their immensely huge numbers, beef and dairy cows, contribute significantly to global warming.

Rotting liquid manure (faeces and urine) in lagoons, ponds and tanks, also produces significant quantities of methane. So vast amounts arise from dairy farms, cattle feedlots and intensive pig farms.5Carlsson-Kanyama A and González AD. 2009. Potential contributions of food consumption patterns to climate change. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 89 (5) 1704S-1709S.

Nitrous oxide (N2O)

Agriculture is also the main contributor of nitrous oxide emissions, which are responsible for 6% of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.2IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, RK Pachauri and LA Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/ 4European Commission. 2017. Climate action, Causes of climate change. https://ec.europa.eu/clima/change/causes_en Fertiliser is the primary source, but manure lagoons associated with large-scale pig farms emit a substantial amount too.

| What are CO2-equivalents? Carbon dioxide equivalents or ‘CO2e’ is a way of describing the global warming potential (GWP) of different greenhouse gases in a common unit. The idea is to express the impact of any greenhouse gas in terms of how much carbon dioxide would produce the same amount of global warming. Over a 100-year period, methane is 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide is 265 times more potent. So one ton of methane has the same effect as 28 tons of carbon dioxide.

The GWP values provided here do not include climate-carbon feedbacks (which would increase the figure for methane to 34 and nitrous oxide to 298).6IPCC. 2013. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, TF, D Qin, G-K Plattner, M Tignor, SK Allen, J Boschung, A Nauels, Y Xia, V Bex and PM Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1535 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1/ |

How fast is global warming happening?

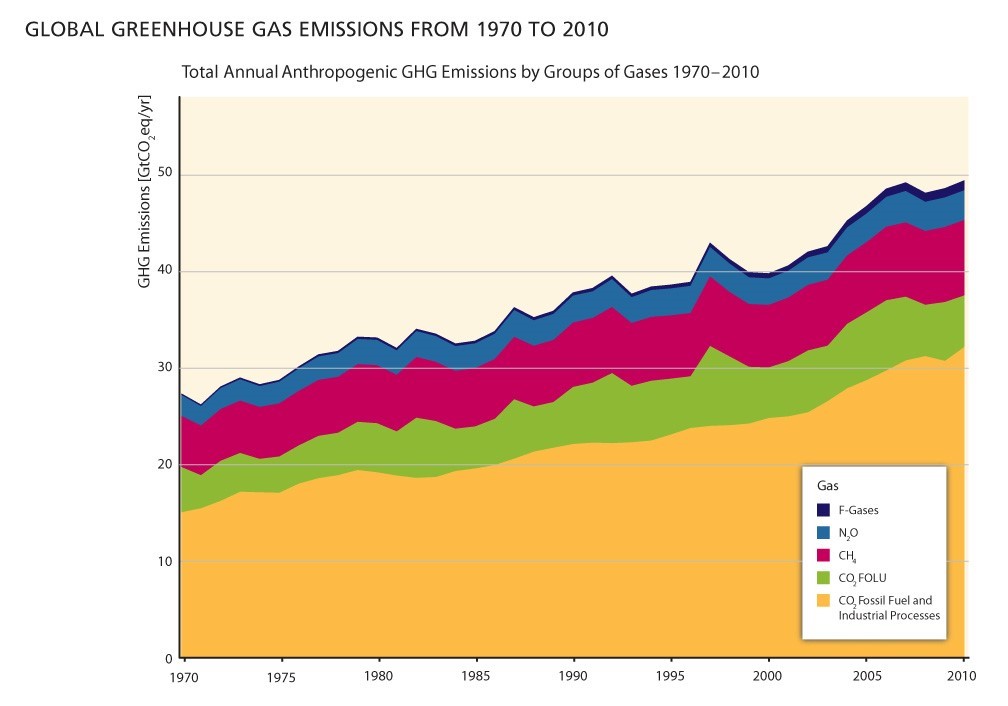

Since the industrial revolution, humans have been producing greenhouse gases in ever-increasing amounts. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the United Nations body for assessing the science related to climate change, say that between 1970 and 2000, anthropogenic greenhouse emissions grew, on average, by 1.3% a year, but between 2000 and 2010, they increased by 2.2% per year.2IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, RK Pachauri and LA Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/

So we are producing increasing amounts year on year, a substantial proportion of this is attributable to animal agriculture. Between 1961 and 2010, emissions coming specifically from livestock increased globally by 51% because of the increased demand for animal foods.7Caro D, Davis SJ, Bastianoni et al. 2014. Global and regional trends in greenhouse gas emissions from livestock. Climatic Change. 126, Issue 1, 203-216.

Source:2IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, RK Pachauri and LA Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/

The amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is now higher than at any time in human history and each of the last three decades has been successively warmer since records began in 1850.2IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, RK Pachauri and LA Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/

Warming of the climate system is unequivocal and since the 1950s, many of the observed changes are unprecedented over decades to millennia. The IPCC says that the atmosphere and ocean have warmed, snow and ice have diminished and sea levels have risen.2IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, RK Pachauri and LA Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/ The effects are escalating in such a way that we may soon reach a critical tipping point beyond which the future looks very uncertain.

It’s happened before

Around 56 million years ago, a large burst of carbon dioxide raised the Earth’s temperature by 5-8°C. This had major impacts on plants and wildlife, scientists think that during this time the poles were ice-free and the Arctic was home to palm trees and crocodiles. It took 200,000 years for the planet to recover from this event, known as the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum (PETM).

Scientists say the PETM was preceded by a more gradual release of greenhouse gases that warmed Earth’s atmosphere by 2-3°C.8Bowen GJ, Maibauer BJ, Kraus MJ et al. 2015. Two massive, rapid releases of carbon during the onset of the Palaeocene–Eocene thermal maximum. Nature Geoscience. 8, 44-47. They suggest that when this heat reached the ocean floor, it melted methane ices called clathrates, releasing huge bursts of methane into the ocean and then the atmosphere.

As methane is many times more potent than carbon dioxide, sudden spikes in emissions could cause huge climate change.9McInerney FA and Wing SL. 2011. The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum: a Perturbation of Carbon Cycle, Climate, and Biosphere with Implications for the Future. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 39, 489-516. It’s unclear what caused the initial release, but scientists say it may have warmed Earth’s atmosphere to similar to levels predicted by the end of this century.

The PETM is an example of catastrophic global warming triggered by the build-up of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. We are currently pumping similar levels of gases into the atmosphere right now, raising concerns that this may also destabilise the Earth’s climate, triggering an environmental disaster.

- Steffen W, Crutzen J and McNeill JR. 2007. The Anthropocene: are humans now overwhelming the great forces of Nature? Ambio. 236 (8) 614-621.

- IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, RK Pachauri and LA Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/

- EPA. 2017. Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-data

- European Commission. 2017. Climate action, Causes of climate change. https://ec.europa.eu/clima/change/causes_en

- Carlsson-Kanyama A and González AD. 2009. Potential contributions of food consumption patterns to climate change. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 89 (5) 1704S-1709S.

- IPCC. 2013. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, TF, D Qin, G-K Plattner, M Tignor, SK Allen, J Boschung, A Nauels, Y Xia, V Bex and PM Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1535 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1/

- Caro D, Davis SJ, Bastianoni et al. 2014. Global and regional trends in greenhouse gas emissions from livestock. Climatic Change. 126, Issue 1, 203-216.

- Bowen GJ, Maibauer BJ, Kraus MJ et al. 2015. Two massive, rapid releases of carbon during the onset of the Palaeocene–Eocene thermal maximum. Nature Geoscience. 8, 44-47.

- McInerney FA and Wing SL. 2011. The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum: a Perturbation of Carbon Cycle, Climate, and Biosphere with Implications for the Future. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 39, 489-516.

Governments around the world have joined together in various treaties and agreements to try and limit global temperature rise to less than 2°C above pre-industrial levels – a critical threshold above which scientists say an increase would take us into unchartered territory.

Many scientists say that the only way we can achieve the emission targets that would help us prevent a climate crisis is to join together globally to combat global warming, most warn that time is running out.

The Kyoto Protocol

The Kyoto Protocol was the first agreement between nations attempting country-by-country reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. The treaty extended the United Nations’ Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) setting mandatory targets for reducing emissions for countries that signed up.1UNFCCC. 2017. The Paris Agreement. http://unfccc.int/paris_agreement/items/9485.php

Under the treaty, 38 developed countries agreed to reduce their annual greenhouse gas emissions from 2008 to 2012 by an average of 5% below 1990 levels. For all three greenhouses gases – carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide – 1990 is used as the baseline year so that all participating nations in agreements such as the Kyoto Protocol share at a common starting point.

Although it was finalised in Kyoto, in Japan, in 1997, owing to the complex ratification process, the Kyoto Protocol didn’t come into force until 2005. During negotiations, the US objected to significant cuts in greenhouse gas emissions and insisted on the trading of carbon allocations being a key element of the treaty. While the US never ratified the Kyoto Protocol, the legacy of its negotiating position made carbon trading a central pillar of international climate policy.2FERN. 2010. Designed to fail? The concepts, practices and controversies behind carbon trading. https://fern.org/designedtofail

Carbon trading

Carbon trading is the process of buying and selling quotas that permit set amounts of greenhouse gas emissions. So if a country’s emissions are lower than its quota, it can sell its surplus, but if it exceeds its limits, it will have to buy an additional quota or cut emissions. Put simply, carbon trading is the process of buying and selling permission to pollute.2FERN. 2010. Designed to fail? The concepts, practices and controversies behind carbon trading. https://fern.org/designedtofail

Some countries only achieved their targets by buying carbon credits and others from carbon leakage – shifting emissions by moving production to developing countries. Emissions released during the production of goods are assigned to the country where they are produced, rather than the country in which they are consumed. This allows rich countries to claim they are reducing or stabilising their emissions when they may be simply sending them elsewhere.

Carbon trading does nothing to reduce global emissions, it simply moves them around. So while emissions from participating nations fell, those in the rest of the world increased sharply – especially in China and other emerging economies, who then exported goods to richer countries.

The US had promised a 7% reduction in emissions under the Kyoto Protocol, but as stated, they did not ratify the agreement. US emissions increased by 17% between 1990 and 2008. If you factor in imports and exports, that figure rises to 25%. For the same period in the UK, emissions fell by 6%, but when outsourcing is considered, that number falls to just a 1% reduction.3Peters GP, Minx JC, Weber CL et al. 2011. Growth in emission transfers via international trade from 1990 to 2008. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (21) 8903-8908.

Glen Peters, from the Centre for International Climate and Environmental Research in Oslo said: “Our study shows for the first time that emissions from increased production of internationally traded products have more than offset the emissions reductions achieved under the Kyoto Protocol.”4Clark D. 2011. Carbon cuts by developed countries cancelled out by imported goods. The Guardian www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/apr/25/carbon-cuts-developed-countries-cancelled So it’s not enough to just consider your own country’s emissions if your consumption is pushing up levels in other countries.

A second period, called the Doha Amendment, ran from 2013 to 2020. During this time, countries committed to reducing emissions by at least 18% below 1990 levels, the European Union (EU) agreed to cut theirs by 20% below that level.5European Commission. 2017. Climate action, 2020 climate & energy package. https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/strategies/2020_en Whilst 136 countries notified their acceptance of the Doha Amendment, it was not formally ratified.

The Kyoto Protocol may not have achieved the substantive success that was hoped for, but it helped pave the way for the Paris Agreement in 2016. At the COP21 sustainable development summit held in Paris, all UNFCCC participants signed the Paris Agreement effectively replacing the Kyoto Protocol. It marked a historic turning point for global climate action, as world leaders came together with a consensus aimed at combating climate change.

The Paris Agreement

The 2016 Paris Agreement did not set legally binding targets, countries that signed up, including the UK, agreed to try and keep the increase in global average temperature to less than 2°C above pre-industrial levels, but ideally, trying to limit the increase to just 1.5°C.

The agreement came into force after the ‘double threshold’ was met when 55 countries accounting for at least 55% of global emissions had signed up.1UNFCCC. 2017. The Paris Agreement. http://unfccc.int/paris_agreement/items/9485.php At present, 191 countries have adopted the Paris Agreement.6UNFCCC. 2020. Paris Agreement – Status of Ratification. https://unfccc.int/process/the-paris-agreement/status-of-ratification Other countries have signed but not ratified the agreement. In 2019, Donald Trump began the process of withdrawing the US from the agreement, and in November 2020, the day after the presidential election, the US was set to become the only country in the world not participating. Within hours of becoming president, Joe Biden moved to recommit to the Paris Agreement and the US has now rejoined.

The 2°C limit is a critical level above which climate scientists believe an increase in global temperature would lead to extreme weather and climate feedbacks that could accelerate the melting of polar ice, which would no longer be able to deflect solar radiation and would also cause dangerously high sea levels. Sea ice reflects about 50% of solar radiation back into space, by contrast water reflects less than 10%. So if you replace ice with water, which is darker, much more solar heat will be absorbed by the ocean and the planet will heat up more rapidly. We simply don’t know what the consequences of this would be. The 1.5°C lower limit offers the planet a better chance of preventing a catastrophe.

From 2023, governments will come together every five years for a global stocktake based on the latest science and progress to date.

The 2008 Climate Change Act

The UK also has its own legislation aimed at combating climate change. The 2008 Climate Change Act set a legally binding target to cut greenhouse gas emissions to 80% below 1990 levels by 2050.7Climate Change Act 2008. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2008/27 This target was based on international ambitions to limit warming to no more than 2°C above pre-industrial levels.

The Paris Agreement moved the goalposts with an aspirational target of limiting warming to 1.5°C. Correspondingly, the 2008 Climate Change Act was amended with a new target of 100% of 1990 levels (net zero) by 2050.7Climate Change Act 2008. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2008/27

The act forms the basis for the UK’s long-term goals of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and ensuring steps are taken towards adapting to the impacts of climate change. In terms of food production, this should mean relying less on imports, which effectively transfer the emissions of food to other countries.

The UK currently imports over 50% of its food and animal feed, so the environmental impact of our food supply is largely displaced overseas. If Europe reduced its livestock production by 50%, then the use of imported soya bean meal would drop by 75% and the EU would become a large net exporter of basic food commodities.8de Ruiter H, Macdiarmid J, Matthews RB et al. 2016. Global cropland and greenhouse gas impacts of UK food supply are increasingly located overseas. Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 13 (114) 20151001.

A word of warning

When people describe ‘direct emissions’ from livestock, they are excluding land-use change emissions, such as deforestation driven by agricultural expansion. Land-use change emissions are a hugely important source of greenhouse gas emissions attributable to global food production that account for 40% of the emissions embedded in UK-consumed food.9Audsley E, Brander M, Chatterton J, et al. 2009. How low can we go? An assessment of greenhouse gas emissions from the UK food system and the scope to reduce them by 2050. FCRN-WWF-UK. http://assets.wwf.org.uk/downloads/how_low_report_1.pdf

Animal foods generate much greater amounts of greenhouse gases than plant foods. UK meat consumption is more than twice the world average and nearly three times that of developing countries.9Audsley E, Brander M, Chatterton J, et al. 2009. How low can we go? An assessment of greenhouse gas emissions from the UK food system and the scope to reduce them by 2050. FCRN-WWF-UK. http://assets.wwf.org.uk/downloads/how_low_report_1.pdf Going vegan is the obvious solution if we are to seriously try and achieve the goals set by the Paris Agreement.

Emission impossible?

Is it possible to keep below a 1.5°C or 2°C global temperature rise, or is it already too late? Scientists say that we can still stop global warming, but right now, the world is failing badly at reaching its climate goals.

In 2015, average global temperatures broke through the 1°C increase barrier, as the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere reached an all-time high.10Met Office. 2016. Global climate in context as the world approaches 1°C above pre-industrial for the first time. www.metoffice.gov.uk/research/news/2015/global-average-temperature-2015 Human activity has now warmed the world by around 1°C higher than pre-industrial levels and the impacts have already been felt in many parts of the world.11IPCC. 2019: Summary for Policymakers. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte V, P Zhai, H-O Pörtner, D Roberts, J Skea, PR Shukla, A Pirani, W Moufouma-Okia, C Péan, R Pidcock, S Connors, JBR Matthews, Y Chen, X Zhou, MI Gomis, E Lonnoy, T Maycock, M Tignor and T Waterfield (eds.)]. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/06/SR15_Summary_Volume_Low_Res.pdf

Writing in the Observer in 2016, Stanford University’s Professor Chris Field, co-chair of the IPCC working group on adaptation to climate change said: “From the perspective of my research I would say the 1.5°C goal now looks impossible or at the very least, a very, very difficult task. We should be under no illusions about the task we face.”12McKie R. 2016. Scientists warn world will miss key climate targets. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2016/aug/06/global-warming-target-miss-scientists-warn

We are now more than halfway to the 2°C temperature rise threshold and the IPCC says that without societal transformation and rapid implementation of ambitious greenhouse gas reduction measures, pathways to limiting warming to 1.5°C and achieving sustainable development will be exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, to achieve.11IPCC. 2019: Summary for Policymakers. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte V, P Zhai, H-O Pörtner, D Roberts, J Skea, PR Shukla, A Pirani, W Moufouma-Okia, C Péan, R Pidcock, S Connors, JBR Matthews, Y Chen, X Zhou, MI Gomis, E Lonnoy, T Maycock, M Tignor and T Waterfield (eds.)]. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/06/SR15_Summary_Volume_Low_Res.pdf

If we want to avert global environmental disaster, we need to take urgent action. We may already be in a situation where we will overshoot targets and then have to attempt to bring the temperature back down using negative emissions technologies that suck carbon dioxide out of the air – like planting trees where they have been cut down (reforestation) and where there were previously none (afforestation).

Cut emissions by how much?

In 2016, a report by the United Nations’ Environment Programme (UNEP) said that the world must cut a quarter from predicted 2030 emissions to keep global warming below the crucial 2°C increase threshold. They warned that without swift reductions, the world is on track for a temperature rise of 2.9-3.4°C this century, even if the pledges agreed in Paris are met.13United Nations. 2016. Report: World must cut further 25% from predicted 2030 emissions. www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2016/11/report-world-must-cut-further-25-from-predicted-2030-emissions/

Erik Solheim, head of UNEP said: “If we don’t start taking additional action now… we will grieve over the avoidable human tragedy. The growing numbers of climate refugees hit by hunger, poverty, illness and conflict will be a constant reminder of our failure to deliver.”

A stark warning, echoing his call from the report’s foreword, where he said: “None of this will be the result of bad weather. It will be the result of bad choices by governments, the private sector and individual citizens. Because there are choices… The science shows that we need to move much faster.”14UN News Centre. 2016. ‘Dramatic’ action needed to cut emissions, slow rise in global temperature – UN Environment report. www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=55464#.WQH4ro-cEhc

Over the last decade, UNEP has tracked where greenhouse gas emissions are heading against where they need to be and highlighted the best ways to close the gap. In their 2019 Emissions Gap Report, they said: “On the brink of 2020, we now need to reduce emissions by 7.6 per cent every year from 2020 to 2030. If we do not, we will miss a closing moment in history to limit global warming to 1.5°C. If we do nothing beyond our current, inadequate commitments to halt climate change, temperatures can be expected to rise 3.2°C above pre-industrial levels, with devastating effect.”15UNEP. 2019. 10 things to know about the Emissions Gap 2019. https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/10-things-know-about-emissions-gap-2019UNFCCC, 2017. Kyoto Protocol. http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/items/2830.php

Other experts paint an even grimmer picture, the IPCC warns that global temperature increases of around 4°C or more above late 20th century levels, combined with increasing food demand, would pose large risks to food security globally.16IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, RK Pachauri and LA Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/

There may still be time to turn things around and the benefits of certain actions could be felt relatively quickly. Professor Peter Stott, Acting Director of the Met Office Hadley Centre said: “It is necessary to reduce greenhouse gas emissions rapidly to help avoid the most dangerous impacts of climate change, but it had been thought that most of the benefits of this early mitigation would be felt only much later in the century. This new research shows that many people alive today could see substantial benefits of efforts to reduce emissions thanks to a greatly reduced risk of heatwaves in as little as two decades.”17Met Office. 2017. Early ‘payback’ with higher emission reductions. https://beta.metoffice.gov.uk/about-us/press-office/news/weather-and-climate/2017/early-payback-from-aggressive-mitigation

Given that animal agriculture contributes at least 14.5% of all anthropogenic greenhouse gases, according to the IPCC, reducing meat and dairy consumption should be a top priority – it could slow global warming very rapidly.

- UNFCCC. 2017. The Paris Agreement. http://unfccc.int/paris_agreement/items/9485.php

- FERN. 2010. Designed to fail? The concepts, practices and controversies behind carbon trading. https://fern.org/designedtofail

- Peters GP, Minx JC, Weber CL et al. 2011. Growth in emission transfers via international trade from 1990 to 2008. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (21) 8903-8908.

- Clark D. 2011. Carbon cuts by developed countries cancelled out by imported goods. The Guardian www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/apr/25/carbon-cuts-developed-countries-cancelled

- European Commission. 2017. Climate action, 2020 climate & energy package. https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/strategies/2020_en

- UNFCCC. 2020. Paris Agreement – Status of Ratification. https://unfccc.int/process/the-paris-agreement/status-of-ratification

- Climate Change Act 2008. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2008/27

- de Ruiter H, Macdiarmid J, Matthews RB et al. 2016. Global cropland and greenhouse gas impacts of UK food supply are increasingly located overseas. Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 13 (114) 20151001.

- Audsley E, Brander M, Chatterton J, et al. 2009. How low can we go? An assessment of greenhouse gas emissions from the UK food system and the scope to reduce them by 2050. FCRN-WWF-UK. http://assets.wwf.org.uk/downloads/how_low_report_1.pdf

- Met Office. 2016. Global climate in context as the world approaches 1°C above pre-industrial for the first time. www.metoffice.gov.uk/research/news/2015/global-average-temperature-2015

- IPCC. 2019: Summary for Policymakers. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte V, P Zhai, H-O Pörtner, D Roberts, J Skea, PR Shukla, A Pirani, W Moufouma-Okia, C Péan, R Pidcock, S Connors, JBR Matthews, Y Chen, X Zhou, MI Gomis, E Lonnoy, T Maycock, M Tignor and T Waterfield (eds.)]. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/06/SR15_Summary_Volume_Low_Res.pdf

- McKie R. 2016. Scientists warn world will miss key climate target. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2016/aug/06/global-warming-target-miss-scientists-warn

- United Nations. 2016. Report: World must cut further 25% from predicted 2030 emissions. www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2016/11/report-world-must-cut-further-25-from-predicted-2030-emissions/

- UN News Centre. 2016. ‘Dramatic’ action needed to cut emissions, slow rise in global temperature – UN Environment report. www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=55464#.WQH4ro-cEhc

- UNEP. 2019. 10 things to know about the Emissions Gap 2019. https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/10-things-know-about-emissions-gap-2019UNFCCC, 2017. Kyoto Protocol. http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/items/2830.php

- IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, RK Pachauri and LA Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/

- Met Office. 2017. Early ‘payback’ with higher emission reductions. https://beta.metoffice.gov.uk/about-us/press-office/news/weather-and-climate/2017/early-payback-from-aggressive-mitigation

Experts warn that current trends could lead to an increase in global temperatures of as much as 5°C above pre-industrial levels by the end of this century. If the warnings are ignored, this human-induced climate change will escalate environmental catastrophes to a whole new level: polar ice melting, rising sea levels, flooding, drought, water shortages, loss of biodiversity, mass extinctions, hurricanes, tornadoes, starvation, infectious disease outbreaks, conflict and warfare.

Despite the clear lack of political will to address the role of diet in the climate crisis, consumers appear to be voting with their wallets.

If we don’t control climate change now some or all of these changes will happen:

- Sea levels will rise

- Glaciers and sea ice will melt

- Coastal cities will flood

- Places that get lots of rain and snowfall will get hotter and drier

- Lakes and rivers will dry up

- Droughts will make it hard to grow crops

- There will be water shortages

- Less reliable and predictable seasons will threaten food security

- Many plants and animals will become extinct

- Hurricanes, tornadoes and storms will become more common

- The likelihood of conflict will increase

- Ocean acidification will destroy marine life

- The loss of wildlife will increase threatening important ecosystems

- Certain diseases will increase, eg malaria and dengue fever1EKOenergy. 2020. Climate change: causes and consequences. https://www.ekoenergy.org/extras/climate-change/

The sea has been rising at a rate of 1.7 millimetres a year since 1900, but this has almost doubled to 3.2 millimetres a year since the end of 20th century.2Mimura N. 2013. Sea-level rise caused by climate change and its implications for society. Proceedings of the Japan Academy Series B Physical and Biological Sciences. 89 (7) 281-301. When described in millimetres, it doesn’t sound like much to worry about, but if the speed at which sea levels are rising continues to accelerate, we can expect a large rise in sea levels this century.

In their report The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, the IPCC investigate how oceans, glaciers and ice sheets will react to global warming. They warn that, if emissions are not reduced, extreme sea-level events such as flooding caused by high waves or storm surges that used to happen once a century will occur every year in many parts of the world by the middle of the century and sea levels will increase by between 61 centimetres and 1.1 metres by 2100.3IPCC. 2019. The ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate. https://report.ipcc.ch/srocc/pdf/SROCC_SPM_Approved.pdf

This could lead to floods in New York, London, Sydney, Vancouver, Mumbai and Tokyo and leave the surrounding areas vulnerable to storm surges (a coastal flood or tsunami-like phenomenon of rising water). Dr Andra Garner, of Rutgers University in New Jersey, fears that if we don’t reduce greenhouse gas emissions, New York could be facing storm surges of 4-5 metres above current sea levels by 2100 and of more than 15 metres above the current sea level by 2300.4Garner AJ, Mann ME, Emanuel KA et al. 2017. Impact of climate change on New York City’s coastal flood hazard: Increasing flood heights from the preindustrial to 2300 CE. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (45) 11861-11866. The coastal flood risk was illustrated in 2012, when Hurricane Sandy’s storm surge of just 2.8 metres above sea level caused an estimated $50 billion worth of damage in New York City.

The ice is melting

Some say the IPCC’s estimates of sea level rises of one metre by 2100 are too conservative as they don’t factor in the disintegration of polar ice sheets. In 2017, a huge ice shelf in Antarctica called Larsen C developed a rift 175 kilometres long and half-a-kilometre wide and a giant iceberg, a quarter of the size of Wales, broke off and drifted into the Weddell Sea.

Shelves like this act as a barrier, holding back glaciers that feed them and following the collapse of the more northerly Larsen A ice shelf in 1995 and Larsen B in 2002, all eyes have been on Larsen C for some time.

The Greenland Ice Sheet (GIS) and West Antarctica Ice Sheet (WAIS) contain ice equivalent to about seven metre and 3-5 metre sea-level rises respectively.5IPCC. 2013: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1535 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1/ The GIS alone could cause a seven-metre sea-level rise if a 3°C increase in global average temperature above pre-industrial levels occurs.6Church JA, Gregory JM, Huybrechts P et al. 2001. Changes in sea level. In Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds. Houghton JT, Ding Y, Griggs DJ, Noguer M, van der Linden PJ, Dai X, Maskell K and Johnson CA). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 639-693. If this higher temperature persists, an irreversible condition, where the GIS never recovers, will be triggered even if the temperature returns to lower values later.7Robinson A, Calov R and Ganopolski A. 2012. Multistability and critical thresholds of the Greenland ice sheet. Nature Climate Change. 2, 429-432.

Potential sea-level rises pose significant threats to coastal areas around the world. Almost two-thirds of the world’s cities with populations of over five million are located in areas at risk of sea-level rise. More than 600 million people (around 10 per cent of the world’s population) live in coastal areas that are less than 10 metres above sea level and about 40% of the world’s population lives within 100 km (about 63 miles) of the sea.8UN Ocean Conference. 2017. Factsheet: People and Oceans. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Ocean-fact-sheet-package.pdf

Continued growth in greenhouse gas emissions could trigger an unstoppable collapse of Antarctica’s ice, raising sea levels by more than a metre by 2100 and more than 15 metres by 2500.9DeConto RM and Pollard D. 2016. Contribution of Antarctica to past and future sea-level rise. Nature. 531 (7596) 591-597. Scientists warn that while atmospheric warming will soon become the dominant driver of ice loss, prolonged ocean warming could delay its recovery for thousands of years.9DeConto RM and Pollard D. 2016. Contribution of Antarctica to past and future sea-level rise. Nature. 531 (7596) 591-597.

Counting the cost of global warming

The Stern Report discussed the effect of global warming on the world economy. They said cutting greenhouse gas emissions would cost a lot of money (about 1% of the world’s GDP), but doing nothing will cost the world a lot more, anything from five-20 times more. They warned that we face losing up to a fifth of the world’s wealth from unmitigated climate change that if unchecked, will devastate the global economy on the scale of the Great Depression or the 20th century’s world wars. Written more than a decade ago, the report said: “So prompt and strong action is clearly warranted.”10Stern N. 2006. Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change Executive Summary. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100407172811/http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/stern_review_report.htm

Climate change will have a devastating impact on food yields around the world. Many areas, for example, sub-Saharan Africa, are likely to be affected in terms of both nutrition and incomes.11McMichael AJ, Powles JW, Butler CD et al. 2007. Food, livestock production, energy, climate change, and health. Lancet. 370 (9594) 1253-1263. Severe crop losses are predicted in areas that already struggle with poor food security, such as South Asia and southern Africa. Scientists predict that over just two decades, Southern Africa could lose more than 30% of its main crop, maize, by 2030 and in South Asia, losses of many regional staples, such as rice, millet and maize could be as high as 10%.12Lobell DB, Burke MB, Tebaldi C et al. 2008. Prioritizing climate change adaptation needs for food security in 2030. Science. 319 (5863) 607-610.

These are just some of the reasons why climate change will affect the lives and safety of large numbers of people around the world.

The true cost of cheap meat is becoming more and more evident. Today, animal agriculture is one of the top contributors to serious environmental problems including the emission of greenhouse gases and global warming.

A 2017 landmark study found that the top three meat firms – JBS, Cargill and Tyson – emitted more greenhouse gases in 2016 than all of France, and the top 20 meat and dairy companies emitted more greenhouse gases in 2016 than all of Germany – Europe’s biggest climate polluter by far. It’s clear that that the world cannot avoid a climate catastrophe without addressing the staggering emissions from the meat and dairy industries.13GRAIN, IATP and Heinrich Böll Foundation. 2017. Big meat and dairy’s supersized climate footprint. www.grain.org/article/entries/5825-bigmeat-and-dairy-s-supersized-climate-footprint

A central problem is the clear lack of transparency in the animal agriculture industries. In 2019, the FAIRR Protein Producer Index ranked 60 of the largest global meat, dairy and fish producers by looking at sustainability risk factors including greenhouse gas emissions, the use of antibiotics and deforestation. Their report said that in stark contrast to the transport sector, only one in four meat, fish and dairy producers even measure their greenhouse gas emissions, let alone act to reduce them.14FAIRR. 2018. Coller Fairr protein producer index. https://www.fairr.org/index/

These 60 producers are the hidden suppliers to household names such as McDonald’s, Burger King and Marks & Spencer. Together, they make up around one-fifth of the global livestock and aquaculture market – that’s one in every five burgers, steaks or fish.

The FAIRR report says: “We now know processing 70 billion animals for 7 billion humans every year produces more than 14% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions – more than the whole transport sector. We know the livestock industry is the single largest driver of habitat loss worldwide. We also know that 73% of all antibiotics are used in factory farming, in many instances to help animals grow faster, accelerating the development of superbugs.”14FAIRR. 2018. Coller Fairr protein producer index. https://www.fairr.org/index/

The Paris Agreement, the FAIRR report says, is impossible to achieve without tackling factory farm emissions.

Put your money where your mouth is!

Ultimately, what the livestock industries produce ends up on the plates of consumers around the world. High-street restaurants, supermarkets and food manufacturers have begun making commitments to reduce or avoid using products associated with deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions. But it seems unlikely they will be able to meet these commitments if their suppliers continue refusing to disclose the information needed.

The FAIRR report notes that plant-based investments are booming with a quarter of animal protein producers (15 out of 60 companies, including traditional meat companies like JBS, Tyson and Marfrig) investing in plant-based proteins such as mock meats.14FAIRR. 2018. Coller Fairr protein producer index. https://www.fairr.org/index/ As the plant-based market is booming, we can only assume, consumers are voting with their wallets.

- EKOenergy. 2020. Climate change: causes and consequences. https://www.ekoenergy.org/extras/climate-change/

- Mimura N. 2013. Sea-level rise caused by climate change and its implications for society. Proceedings of the Japan Academy Series B Physical and Biological Sciences. 89 (7) 281-301.

- IPCC. 2019. The ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate. https://report.ipcc.ch/srocc/pdf/SROCC_SPM_Approved.pdf

- Garner AJ, Mann ME, Emanuel KA et al. 2017. Impact of climate change on New York City’s coastal flood hazard: Increasing flood heights from the preindustrial to 2300 CE. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (45) 11861-11866.

- IPCC. 2013: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1535 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1/

- Church JA, Gregory JM, Huybrechts P et al. 2001. Changes in sea level. In Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds. Houghton JT, Ding Y, Griggs DJ, Noguer M, van der Linden PJ, Dai X, Maskell K and Johnson CA). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 639-693.

- Robinson A, Calov R and Ganopolski A. 2012. Multistability and critical thresholds of the Greenland ice sheet. Nature Climate Change. 2, 429-432.

- UN Ocean Conference. 2017. Factsheet: People and Oceans. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Ocean-fact-sheet-package.pdf

- DeConto RM and Pollard D. 2016. Contribution of Antarctica to past and future sea-level rise. Nature. 531 (7596) 591-597.

- Stern N. 2006. Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change Executive Summary. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100407172811/http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/stern_review_report.htm

- McMichael AJ, Powles JW, Butler CD et al. 2007. Food, livestock production, energy, climate change, and health. Lancet. 370 (9594) 1253-1263.

- Lobell DB, Burke MB, Tebaldi C et al. 2008. Prioritizing climate change adaptation needs for food security in 2030. Science. 319 (5863) 607-610.

- GRAIN, IATP and Heinrich Böll Foundation. 2017. Big meat and dairy’s supersized climate footprint. www.grain.org/article/entries/5825-bigmeat-and-dairy-s-supersized-climate-footprint

- FAIRR. 2018. Coller Fairr protein producer index. https://www.fairr.org/index/

As food production expands to meet the world’s growing appetite for meat, emissions from animal agriculture continue to rise. The only way to stop this is to change the way we eat, we need to drastically reduce animal food production.

Simply using energy efficient light bulbs or switching to an electric car will make little difference if you continue tucking into steak and eating burgers.

The United Nations’ ground-breaking report, Livestock’s Long Shadow surprised some people when it revealed how livestock farming is responsible for more greenhouse gas emissions than all the world’s transport – cars, buses, trucks, trains, ships and planes – put together.1FAO. 2006. Livestock’s Long Shadow. www.fao.org/docrep/010/a0701e/a0701e00.HTM Henning Steinfeld, Chief of the Food and Agriculture Organisation’s Livestock Information and Policy Branch and senior author of the report said: “Livestock are one of the most significant contributors to today’s most serious environmental problems. Urgent action is required to remedy the situation.”2FAO. 2008. Livestock a major threat to environment. www.fao.org/Newsroom/en/news/2006/1000448/index.html

The report estimated that livestock accounts for around a fifth (18%) of all man-made greenhouse gas emissions.1FAO. 2006. Livestock’s Long Shadow. www.fao.org/docrep/010/a0701e/a0701e00.HTM This figure was based on comprehensive analysis that included the production of draft power (animals used for pulling heavy loads), eggs, wool and dairy products. A later estimate, and the one most widely used currently, puts the figure at 14.5%, but only includes meat, poultry, eggs and dairy production.3Gerber PJ, Steinfeld H, Henderson B et al. 2013. Tackling climate change through livestock – A global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAO, Rome, Italy. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3437e.pdf

However, the situation may be even worse than previously thought. Revised calculations show that global livestock methane emissions in 2011 were 11% higher than estimates made by IPCC in 2006.4Wolf J, Asrar GR and West TO. 2017. Revised methane emissions factors and spatially distributed annual carbon fluxes for global livestock. Carbon Balance Management. 12 (1) 16. The reason the figure may be so much higher is that breeding and feeding methods have changed, so earlier estimates were based on out-of-date data. Dr Julie Wolf, of the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Research Service said: “In many regions of the world, livestock numbers are changing, and breeding has resulted in larger animals with higher intakes of food. This, along with changes in livestock management, can lead to higher methane emissions.”5BMC. 2017. Global methane emissions from agriculture are larger than reported, according to new estimates. www.biomedcentral.com/about/press-centre/science-press-releases/29-09-17

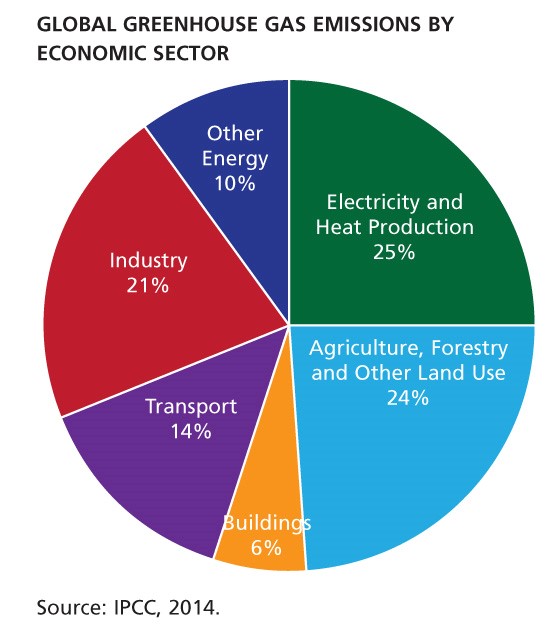

In 2014, the IPCC said that around a quarter (24%) of all global greenhouse emissions came from agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) – more than from either transport or industry.6IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, RK Pachauri and LA Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/ Writing in the Lancet, Australian public health researcher Professor Anthony J. McMichael said “Greenhouse-gas emissions from the agriculture sector account for about 22% of global total emissions; this contribution is similar to that of industry and greater than that of transport. Livestock production (including transport of livestock and feed) accounts for nearly 80% of the sector’s emissions.”7McMichael AJ, Powles JW, Butler CD et al. 2007. Food, livestock production, energy, climate change, and health. Lancet. 370 (9594) 1253-1263.

The figures vary, but the general consensus is that animal agriculture is responsible for around a fifth of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.

Emissions from livestock production are calculated based on the following:

- Deforestation for grazing land and soya-feed production

- Soil carbon loss in grazing lands

- Energy used in growing feed-grains

- Energy used in processing and transporting grains and meat

- Nitrous oxide releases from the use of nitrogenous fertilisers

- Gases from animal manure (especially methane)

- Enteric fermentation7McMichael AJ, Powles JW, Butler CD et al. 2007. Food, livestock production, energy, climate change, and health. Lancet. 370 (9594) 1253-1263.

McMichael suggests that livestock production accounts for around 9% of all carbon dioxide emissions, 35-40% of methane emissions and 65% of nitrous oxide emissions.7McMichael AJ, Powles JW, Butler CD et al. 2007. Food, livestock production, energy, climate change, and health. Lancet. 370 (9594) 1253-1263.

Methane emissions

Methane is the second greatest contributor to anthropogenic climate change and emissions from ruminant livestock have more than tripled since pre-industrial times and continue to rise rapidly.8Dangal SR, Tian H, Zhang B et al. 2017. Methane emission from global livestock sector during 1890-2014: magnitude, trends and spatio-temporal patterns. Global Change Biology. 23, 10, 4147-4161. Over the last decade, emissions from agriculture in the UK have not fallen. In 2017, agriculture in the UK was the source of 50% of methane emissions.9Defra. 2019. Agricultural Statistics and Climate Change 9th Edition July 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/agricultural-statistics-and-climate-change

Methane is produced from enteric fermentation and from the decomposition of manure under anaerobic conditions. When manure is stored or treated as a liquid in a lagoon, pond or tank it decomposes anaerobically (without air) and produces significant quantities of methane. When manure is deposited on pastures, it tends to decompose aerobically (with air) and little or no methane is produced. Hence, how manure is dealt with or managed affects emission rates.9Defra. 2019. Agricultural Statistics and Climate Change 9th Edition July 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/agricultural-statistics-and-climate-change

The meat and dairy industries suggest that improving efficiency and developing technologies could be used to reduce emissions. The Agriculture Industry GHG Action Plan: Framework for Action, published in February 2010, outlined how reductions could be made through greater resource efficiency, generally involving changes in farming practice such as improving nutrient management through the efficient use of fertilisers or slurry/manures for example.9Defra. 2019. Agricultural Statistics and Climate Change 9th Edition July 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/agricultural-statistics-and-climate-change

However, the 2019 Farm Practices Survey found that when asked how important it is to consider greenhouse gases when taking decisions about crops, land and livestock, just 13% of farmers said ‘very important’, 42% thought it ‘fairly important’, 29% thought it was ‘not very important’, 8% said ‘not important at all’ and a further 8% thought their farm did not produce greenhouse gases.9Defra. 2019. Agricultural Statistics and Climate Change 9th Edition July 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/agricultural-statistics-and-climate-change It’s difficult to imagine the industry taking a lead on action to reduce emissions with these attitudes among farmers!

Some factory farms use methane digesters to produce electricity. This technology may reduce methane emissions but doesn’t eliminate solid waste and typically requires large subsidies to remain economically viable. So, despite being touted as a ‘clean’ energy source, methane digesters effectively serve to further entrench the environmentally destructive model of industrial livestock production.

Scientists have said that available technologies for reducing emissions from livestock would reduce them by less than 20%.7McMichael AJ, Powles JW, Butler CD et al. 2007. Food, livestock production, energy, climate change, and health. Lancet. 370 (9594) 1253-1263. Current trends in yield improvement will not be sufficient to meet projected global food demand by 2050. Changing the way we farm animals will not be enough, a decrease in agriculture-related emissions can only be achieved by a reduction in demand for animal foods. Switching to improved diets and reducing food waste will be essential if we are to reduce emissions and to provide enough food for the global population of 2050.10Bajželj B, Richards KS, Allwood JM et al. 2014. Importance of food-demand management for climate mitigation. Nature Climate Change. 4, 924-929.

If nothing changes, greenhouse gas emissions from livestock will continue to rise as food production expands to meet the increasing demand from the world population which is expected to reach 8.6 billion by 2030 and 9.8 billion by 2050.11UN DESA. 2017. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables. Working Paper No. ESA/P/WP/248. https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/publications/files/wpp2017_keyfindings.pdf

Writing in the Lancet, scientists say: “Assuming a 40% increase in global population by 2050 and no advance in livestock-related greenhouse gas reduction practices, global meat consumption would need to fall to an average of 90g per person per day just to stabilise emissions from this sector.” This would mean a substantial drop in meat consumption in wealthy countries (90g is less than half the average intake in the UK) and restricted growth in demand in developing countries, especially of red meat from ruminants.7McMichael AJ, Powles JW, Butler CD et al. 2007. Food, livestock production, energy, climate change, and health. Lancet. 370 (9594) 1253-1263.

Greenhouse gas emissions from livestock production warrant the same scrutiny as those from driving and flying. The solution isn’t just dropping meat alone from your diet – after beef, dairy is the most emission-intensive livestock product accounting for 20% of the total greenhouse gases emitted by animal agriculture; more than pig meat, poultry and eggs combined.3Gerber PJ, Steinfeld H, Henderson B et al. 2013. Tackling climate change through livestock – A global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAO, Rome, Italy. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3437e.pdf In the EU, the situation is reversed with the dairy sector producing the most greenhouse gases, closely followed by beef.12Lesschen JP, van den Berg M, Westhoek HJ et al. 2011. Greenhouse gas emission profiles of European livestock sectors. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 166-167, 16-28.

Emissions from the global dairy sector account for 4% of the total global greenhouse gas emissions.13Gerber PJ, Vellinga T, Opio C et al. 2010. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from the Dairy Sector, a Life Cycle Assessment. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Animal Production and Health Division, Rome, Italy. www.fao.org/3/k7930e/k7930e00.pdf This is a significant amount, especially when you consider that dairy foods are only produced for a quarter of the world’s population – 75% of people in the world are lactose intolerant and do not consume milk or dairy products.

The beef with beef

Beef production is one of the most environmentally damaging industries worldwide. In terms of efficiency rates of converting animal feed into human food, when you look at the amount of carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e) produced per kilogram of food in the EU, beef is the worst at 22.6 kg CO2e per kg followed by pork (3.5), eggs (1.7), poultry (1.6) and milk (1.3).12Lesschen JP, van den Berg M, Westhoek HJ et al. 2011. Greenhouse gas emission profiles of European livestock sectors. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 166-167, 16-28.

Beef is responsible for the release of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide, vast losses of carbon sinks in land-use changes, biodiversity loss, rainforest destruction, water pollution and excessive water wastage. It’s one of the most inefficient foods you could possibly eat – as much of the food cows consume is excreted when humans could have consumed those calories directly. ‘But humans don’t eat grass’ we hear the industry cry, well neither do vast numbers of cattle. A third of the world’s cereal harvest is fed to livestock and the vast majority of soya grown, especially in areas like the Amazon, is fed to animals raised for meat, which is another reason why beef tops the charts.

Importing meat and dairy foods is not the answer. Whilst livestock production in the UK may have declined since 1990, some domestic production (in particular meat) has been replaced with imports. Therefore, any reduction of emissions in the UK will have been at the expense of increases overseas. This type of carbon leakage does not reduce global emissions: “…agricultural activity in UK emissions has to be viewed in the broader policy context, including the demand for food. Failure to take action to reduce emissions in the UK could result in “carbon leakage”, where production moves abroad. This would not reduce overall global GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions and could put pressure on sensitive landscapes or habitats overseas.”9Defra. 2019. Agricultural Statistics and Climate Change 9th Edition July 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/agricultural-statistics-and-climate-change

The best solution is to stop eating meat, fish, dairy and eggs, mirroring the widely supported strategy proposed for greenhouse gas emissions in general. We talk the talk with sustainable energy and electric cars – let’s walk the walk with diet!

- FAO. 2006. Livestock’s Long Shadow. www.fao.org/docrep/010/a0701e/a0701e00.HTM

- FAO. 2008. Livestock a major threat to environment. www.fao.org/Newsroom/en/news/2006/1000448/index.html

- Gerber PJ, Steinfeld H, Henderson B et al. 2013. Tackling climate change through livestock – A global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAO, Rome, Italy. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3437e.pdf

- Wolf J, Asrar GR and West TO. 2017. Revised methane emissions factors and spatially distributed annual carbon fluxes for global livestock. Carbon Balance Management. 12 (1) 16.

- BMC. 2017. Global methane emissions from agriculture are larger than reported, according to new estimates. www.biomedcentral.com/about/press-centre/science-press-releases/29-09-17