Swine Flu – Piggy in the Middle

Some researchers are even more worried about pigs than poultry. Professor Gregory Gray, an epidemiologist at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina in the US, describes pigs as ideal “mixing vessels” for flu viruses.1Willyard C. 2019. Flu of the Farm. Nature. 573 (7774) S62-S63. This, Gray says, is because pigs are susceptible to infection with flu viruses from other pigs, humans and birds.

If pigs are infected with more than one virus, the viruses can “mix and match” to produce a new strain, previously unseen. This mixing of genes is called “reassortment” and occurs commonly with flu viruses. It’s why we have a new seasonal flu vaccine every year – to keep up to date with the new strains circulating.

Reassortment led to the emergence of the viruses responsible for the 1957 Asian flu and 1968 Hong Kong flu pandemics, caused by the mixing of bird and human viruses, possibly in pigs.2Nelson MI and Worobey M. 2018. Origins of the 1918 pandemic: revisiting the swine ‘mixing vessel’ hypothesis. American Journal of Epidemiology. 187 (12) 2498-2502.

The H1N1 virus responsible for the 2009 swine flu pandemic was definitely of swine origin. It had an unusual mix of genetic sequences from birds, humans and pigs. This came about following the mixing of live pigs through international trade, creating the ideal conditions for different viruses to mix with devastating consequences. Moving live pigs between Eurasia and North America facilitated the mixing of different swine flu viruses, leading to the genesis of a completely new one, never seen before. At the time, scientists said: “Recent reports of widespread transmission of swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) viruses in humans in Mexico, the United States, and elsewhere highlight this ever-present threat to global public health.”3Shinde V, Bridges CB, Uyeki TM et al. 2009. Triple-reassortant swine influenza A (H1) in humans in the United States, 2005-2009. New England Journal of Medicine. 18, 360 (25) 2616-25.

Before the 2009 pandemic, for at least 80 years, so-called “classical swine H1N1” viruses, containing elements from birds, humans and pigs (triple-reassortant viruses), had been circulating in North American pigs.4CDC. 2009. Origin of 2009 H1N1 Flu (Swine Flu): Questions and Answers. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/information_h1n1_virus_qa.htm [Accessed 31 May 2022]. Scientists say that between the 1930s and 1990s, H1N1 underwent little change. However, by the late 1990s, multiple strains and subtypes (H1N1, H1N2 and H3N2) of triple-reassortant swine flu viruses – containing gene segments from birds, humans and pigs – had emerged and become predominant among North American pigs.3Shinde V, Bridges CB, Uyeki TM et al. 2009. Triplereassortant swine influenza A (H1) in humans in the United States, 2005-2009. New England Journal of Medicine. 18, 360 (25) 2616-25.

The 2009 so-called “quadruple-reassortant” virus included additional segments from Eurasian pigs.4CDC. 2009. Origin of 2009 H1N1 Flu (Swine Flu): Questions and Answers. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/information_h1n1_virus_qa.htm [Accessed 31 May 2022]. Once this new virus infected humans, swine flu spread quickly around the world, reaching pandemic status in just two months.1Willyard C. 2019. Flu of the Farm. Nature. 573 (7774) S62-S63. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that 150,000 to 575,000 people died from swine flu in the first year of the outbreak.5Dawood FS, Iuliano AD, Reed C et al. 2012. Estimated global mortality associated with the first 12 months of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 virus circulation: a modelling study. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 12 (9) 687-695. Unlike other seasonal flu epidemics, 80 per cent of deaths occurred in people under 65 with the highest burden of infection occurring in those aged five to 24 years old.6Le Sage V, Jones JE, Kormuth KA et al. 2021. Preexisting heterosubtypic immunity provides a barrier to airborne transmission of influenza viruses. PLoS Pathogens. 18, 17(2) e1009273.

Scientists think that most older people had some protection because they would have been exposed to similar flu viruses descended from the one that caused the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic – an old strain of H1N1 that their body still remembered. Younger people, on the other hand, may have only been exposed to H3N2 which offered no protection against the new swine flu virus. Swine flu has now become one of the seasonal flu viruses that circulate each winter. If you’ve had flu in the last few years, there’s a chance it was caused by this virus.

Reassortment occurs frequently in nature and, although it rarely results in a virus with pandemic potential, scientists say that all three pandemics of the twentieth century may have been generated by a series of multiple reassortment events in pigs or humans.

The genesis of the 2009 swine flu pandemic followed a recognised evolutionary pathway. Initial transmission to humans appears to have occurred several months before the outbreak. It may have taken years for all the elements that made up the final virus to come together, highlighting the need for the systematic surveillance of flu in pigs as a means of identifying potentially pandemic strains before they cross into human populations. Scientists say that “…despite widespread influenza surveillance in humans, the lack of systematic swine surveillance allowed for the undetected persistence and evolution of this potentially pandemic strain for many years.”7Smith G, Vijaykrishna D, Bahl J et al. 2009. Origins and evolutionary genomics of the 2009 swine-origin H1N1 influenza A epidemic. Nature. 459, 1122-1125.

The World Organisation for Animal Health, formerly the Office International des Epizooties (OIE), is an intergovernmental body that sets standards for reporting animal disease. They require that certain strains of avian influenza be declared, but pork producers do not need to report swine flu to the authorities. So, flu viruses in pigs often go undetected and unreported. According to Professor Gray: “Influenza A viruses are largely tolerated because they don’t cause a big problem, at least not in the pigs.”1Willyard C. 2019. Flu of the Farm. Nature. 573 (7774) S62-S63.

H1N1 strains continue to circulate in pigs in the US and Asia. H3N2 viruses are now endemic in pigs in southern China, where they co-circulate with H9N2 viruses with the potential of reassortment with H5N1. In Spain, H1N1, H1N2 and H3N2 viruses circulate concurrently in pigs.8Leibler JH, Otte J, Roland-Holst D et al. 2009. Industrial food animal production and global health risks: exploring the ecosystems and economics of avian influenza. Ecohealth. 6 (1) 58-70. A flu virus circulating in pigs reassorting with bird and human viruses to generate a new swine flu virus could represent a future influenza pandemic threat for humans, as highlighted by the last 2009 swine flu pandemic.9He P, Wang G, Mo Y et al. 2018. Novel triplereassortant influenza viruses in pigs, Guangxi, China. Emerging Microbes and Infections. 7 (1) 85.

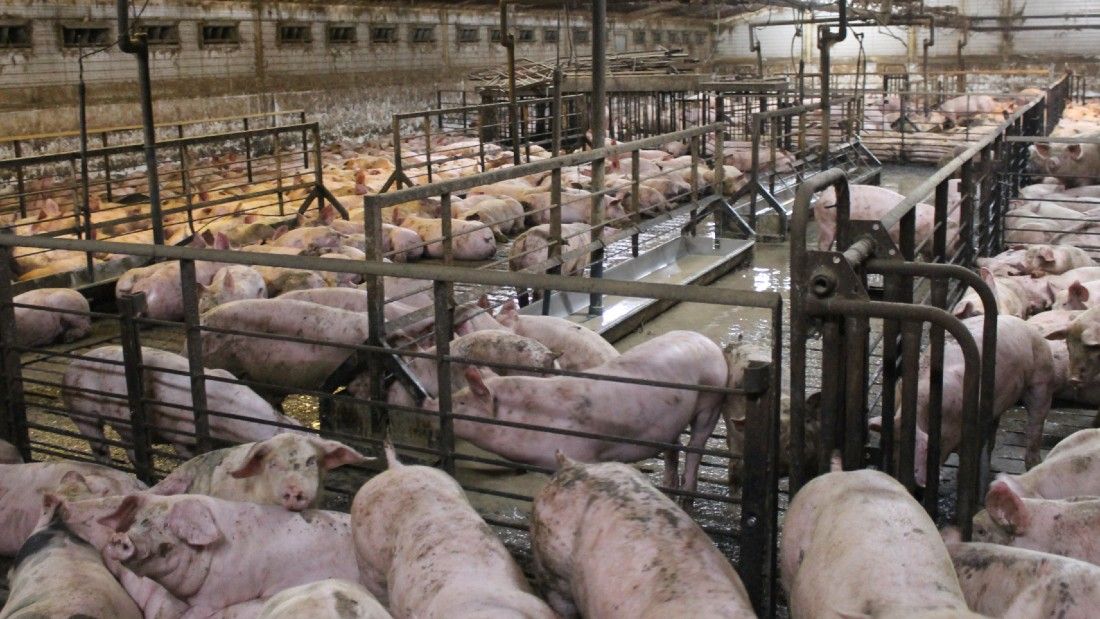

Scientists say: “The emergence of variant influenza viruses that transmit efficiently from person to person and for which little population immunity exists may increase the possibility of an influenza pandemic.”10Epperson S, Jhung M, Richards S et al. 2013. Human infections with influenza A(H3N2) variant virus in the United States, 2011-2012. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 57 Suppl 1, S4-S11. Science writer Willyard warns: “Modern farms are particularly vulnerable to devastation from influenza. A large farm might hold tens of thousands of chickens or thousands of pigs in the name of efficient protein production, and this creates an opportunity for viruses such as influenza to mutate and spread. But there is an even greater fear: that these ever-changing viruses will give rise to the next human pandemic.”1Willyard C. 2019. Flu of the Farm. Nature. 573 (7774) S62-S63. Given the potential role pigs play in the emergence of novel flu viruses, placing intensive poultry and pig farms close together could further increase the risk.8Leibler JH, Otte J, Roland-Holst D et al. 2009. Industrial food animal production and global health risks: exploring the ecosystems and economics of avian influenza. Ecohealth. 6 (1) 58-70.

The way the 2009 swine flu pandemic would occur was predicted in a review published just months before it began: “ recent events resulting in the establishment and isolation of reassorted, mammalian-adapted H2N3 viruses from pigs in the US should remind scientists, medical doctors, veterinarians and farmers that the creation of novel reassortant swine influenza viruses with zoonotic and pandemic potential could also happen in modern swine facilities in the backyard of a highly industrialised country in North America or Western Europe.”12Ma W, Kahn RE, Richt JA. 2008. The pig as a mixing vessel for influenza viruses: Human and veterinary implications. Journal of Molecular Genetic Medicine. 3 (1) 158-166. Within a few months of this review being published, the world faced an influenza pandemic for the first time in 40 years. The next one could be a lot sooner according to some scientists.

The authors of this review also warned that: “Even though pigs can generate novel influenza viruses capable of infecting humans, at present it is difficult to predict which particular virus will cause the next human influenza pandemic. The index case (patient zero) probably linking a wild bird, chicken or domestic duck with a pig and/or a person could be anywhere in the world, but a Southeast Asian ‘wet market’ is most likely to be the locale in which the next pandemic virus is generated.”11Ma W, Kahn RE, Richt JA. 2008. The pig as a mixing vessel for influenza viruses: Human and veterinary implications. Journal of Molecular Genetic Medicine. 3 (1) 158-166. The wet market scenario described is the most likely location from which the coronavirus pandemic emerged a decade later but it could just as easily have been a bird flu virus.

A new animal virus could jump to humans tomorrow and start another pandemic, which could be far worse than the 2009 swine flu or Covid-19 pandemics. We are sitting on a ticking time bomb! The best way to prevent another pandemic is to end factory farming.