Covid-19, SARS and MERS – Driven by the Hunger for Meat

The coronavirus pandemic may have originated, it is thought, in a wet market rather than a factory farm, but the risk factors in such places are very similar. The increasing global demand for meat from both wild and domesticated animals poses a serious pandemic threat – whether it comes from a wet market or a factory farm.1Cheng ZJ, Qu HQ, Tian L, et al. 2020. COVID-19: Look to the Future, Learn from the Past. Viruses. 12 (11) 1226.

Evolutionary biologist Rob Wallace of the Agroecology and Rural Economics Research Corps in St Paul, Minnesota told the Guardian: “We can blame the object – the virus, the cultural practice – but causality extends out into the relationships between people and ecology.”2Spinney L. 2020. Is factory farming to blame for coronavirus? Available: www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/28/is-factory-farming-to-blame-for-coronavirus [Accessed 1 June 2022].

Even when zoonotic diseases come from wildlife, factory farming often has a role to play. In China, for example, as industrialised farming has expanded, small scale farmers have moved over to the wildlife market. They have also been geographically pushed into remote areas inhabited by bats, for example. We’ve seen the same thing with people catching Ebola from chimpanzees caught and slaughtered as ‘bushmeat.’

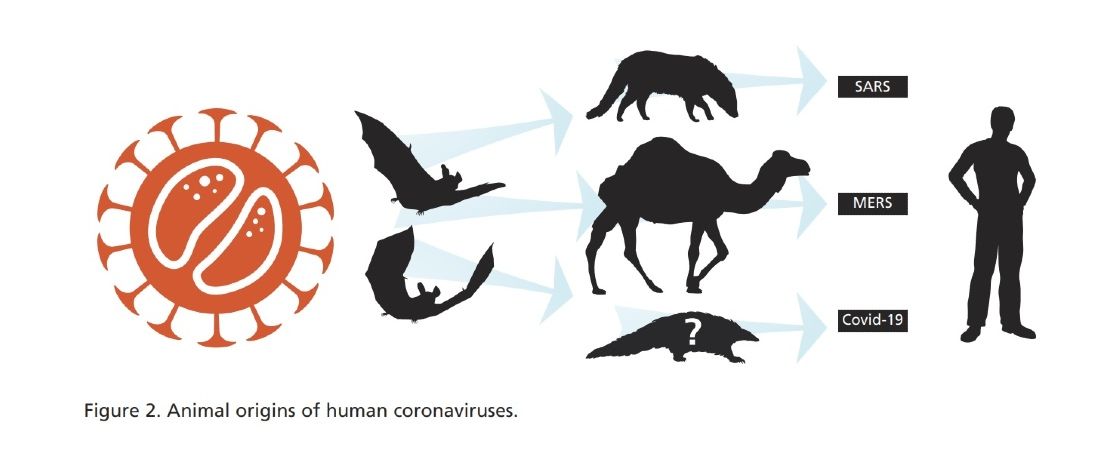

The severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, outbreak in 2002-2003 was the first global pandemic of the 21st century followed by Middle East respiratory syndrome, or MERS, in 2012. SARS, MERS and Covid-19 are all caused by coronaviruses believed to originally come from bats (the so-called natural hosts). However, it is most likely that these viruses were only able to infect humans after mutating in an intermediate host animal.

The intermediate hosts for SARS and MERS were civets and camels, respectively. Civets are captured in the wild and brought to market to be sold for their meat. Camels are raised for milk, meat, fibre (wool and hair) as well as transport and racing. For Covid-19, various candidate intermediate hosts have been proposed including pangolins, which have been illegally sold in Chinese markets3Rabi FA, Al Zoubi MS, Kasasbeh GA et al. 2020. SARSCoV-2 and Coronavirus Disease 2019: What We Know So Far. Pathogens. 9 (3)231. and are the most trafficked animal in the world. Raccoon dogs, another candidate, are farmed for their fur and housed in large numbers with more than 14 million captive raccoon dogs in China.4Freuling CM, Breithaupt A, Müller T et al. 2020. Susceptibility of Raccoon Dogs for Experimental SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 26 (12) 2982-2985.

If SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, was transmitted from bats to humans directly – there was ample opportunity. Over 100 species of bat are eaten globally, including the horseshoe bats which naturally harbour coronaviruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2.5Burki T. 2020. The origin of SARS-CoV-2. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 20 (9) 1018-1019.

Writing in The Lancet, scientists said: “Learning from the SARS outbreak, which started as animal-to-human transmission during the first phase of the epidemic, all game meat trades should be optimally regulated to terminate this portal of transmission.”6Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH et al. 2020. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. The Lancet. 395 (10223)514-523. Wet markets in China were closed temporarily after the SARS outbreak, though this ban did not last long.7Aguirre AA, Catherina R, Frye H et al. 2020. Illicit Wildlife Trade, Wet Markets, and COVID-19: Preventing Future Pandemics. World Medical Health Policy. 10.1002/wmh3.348.

In January 2020, following the outbreak of Covid-19, the Chinese government again announced a temporary ban on the sale of wild animal products at wet markets and then a permanent ban on wildlife trade in February 2020 with exceptions for fur farming and medicine. Unfortunately, these loopholes mean that many wild animals remain unprotected and could potentially lead to another pandemic caused by a zoonotic disease in the future.

By the end of March 2020, most of the wet markets in China were reopened without wild animals or wild meat. The World Health Organisation responded with the recommendation that wet markets only be reopened on the condition that they conform to stringent food safety and hygiene standards. The latest statement makes clear their belief that live animal markets pose a big risk in creating novel viruses in the future. In April 2020, the Chinese government unveiled plans to further tighten restrictions on wildlife trade.

In April 2021, the World Health Organisation, World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) and the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) joined forces to call for a complete ban on the sale of live caught wild animals in food markets across the world. They called on countries to abolish the trade of “live caught wild animals of mammalian species”8UN News. 2021. WHO and partners urge countries to halt sales of wild mammals at food markets. Available: https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/04/1089622 [Accessed 1 June 2022] in a bid to stop a repeat of the Covid-19 pandemic. They also want to see improvements in standards of hygiene and sanitation including handwashing, pest control and waste management. In a joint statement they said: “Traditional markets, where live animals are held, slaughtered and dressed, pose a particular risk for pathogen transmission to workers and customers alike.”9WHO. 2021. Reducing public health risks associated with the sale of live wild animals of mammalian species in traditional food markets. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Food-safety-traditional-markets-2021.1 [Accessed 1 June 2022].

Wet markets place people, live and dead animals in constant close contact. Animals including chickens, ducks, pigs, snakes, civets, pangolins, bats, raccoon dogs, beavers, foxes, dogs and many other animals are sold, skinned and slaughtered in front of customers, sending a cocktail of microorganisms into the air. The dreadful, cramped conditions and mix of wild and domestic creatures, alongside the throngs of people provides an ideal environment for zoonotic diseases to jump from animals to humans. Another pandemic in the making.

Most of the wild animals traded in China are live, says Chris Walzer, a veterinary physician with the Wildlife Conservation Society in New York City. “You bring all those naturally distant species to one location, so there are more chances to incubate and generate a new virus” says Qiuhong Wang, a virologist at the Ohio State University in Wooster.10Lewis D. 2021. Can COVID spread from frozen wildlife? Scientists probe pandemic origins. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/d41586-021-00495-0.

In December 2019, a cluster of cases of pneumonia were reported from Wuhan City in China. The cause was a coronavirus, similar to the SARS-CoV-1 virus that caused the SARS pandemic. Soon to be called Covid-19, the disease spread fast across Asia to the US, Europe and so on, becoming a global pandemic in less than three months.

Mink, among other animals, can act as a reservoir for coronaviruses. Farmed mink are highly susceptible to infection with SARS-CoV-2 – the virus that causes Covid-19. They can catch it from humans, pass it on to each other and spread it back to humans.

In April 2020, SARS-CoV-2 was reported from two mink fur farms in the Netherlands. Evidence suggests that the virus was transmitted to the mink via infected farm workers. Transmission from human-to-mink and mink-to-human has now been well-established. Once Covid-19 reaches a mink farm, scientists say, it spreads very rapidly among the animals and one worry is that infected mink farms can become a viral reservoir for new outbreaks in humans. More recently, infections in minks have been reported in Denmark, Netherlands, Italy, Spain, Sweden and the US.11Larsen CS and Paludan SR. 2020. Corona’s new coat: SARSCoV-2 in Danish minks and implications for travel medicine. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 38, 101922.

Mink fur farms have provided the perfect environment for the virus to mutate and then spread back to humans raising concerns that a mutated version (or variant) might be even more deadly or may hamper the development of a vaccine. Since June 2020, over 200 human cases of Covid-19 have been identified in Denmark with SARS-CoV-2 variants associated with farmed minks, including 12 caused by a mutated variant.12WHO. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 mink-associated variant strain – Denmark. Available: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2020-DON301 [Accessed 1 June 2022].

The human-mink-human transmission shows the real danger of what virologists call “reverse spillover” and demonstrates what a potential danger factory farms pose: “It is a fundamental part of viral evolution that a virus will change over time and accumulate mutations, but one should be particularly concerned when viruses pass between species, including humans and animals.”11Larsen CS and Paludan SR. 2020. Corona’s new coat: SARSCoV-2 in Danish minks and implications for travel medicine. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 38, 101922.

Credit Jo-Anne McArthur, Djurrattsalliansen

Concerned about new variants arising from mink farms, the Danish prime minister warned that in a worst-case scenario, they “could cause a second pandemic and Denmark could become the new Wuhan. In addition, vaccines under development might not be effective.”11Larsen CS and Paludan SR. 2020. Corona’s new coat: SARSCoV-2 in Danish minks and implications for travel medicine. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 38, 101922.

The Danish government ordered the country’s entire mink herd – one of the world’s biggest – to be culled in November 2020. At that time, there was no legal basis for the mass cull, however it proceeded and some 17 million mink were culled. Then, in a grim twist to the tale, some of the mink buried in mass graves resurfaced as gas from their decomposing bodies pushed them up out of the ground. Amid concerns that drinking water could become contaminated, it was decided that their bodies should be exhumed and incinerated. In May 2021, Denmark began digging up millions of the culled minks buried six months earlier. The silver lining is that the whole episode has been a death knell for one of the cruellest industries in the world, the fur industry. Denmark was the world’s biggest producer of mink fur exporting mainly to China and Hong Kong – but not anymore. The Netherlands, another top exporter, fast-tracked a plan to phase out fur farming, bringing the deadline forward from 2024 to 2020. France has announced that it will ban farming mink for fur by 2025 and Poland may follow suit. Fur farming is already banned in the UK and has been for 20 years.

It’s not just a case of banning fur farms and wet markets, although that can’t come soon enough. We need to stop factory farming too. “In the meantime, the scientific community should be vigilant about the possibility of return of another coronavirus in another one or two decades.”1Cheng ZJ, Qu HQ, Tian L, et al. 2020. COVID-19: Look to the Future, Learn from the Past. Viruses. 12 (11) 1226.