Antibiotic Resistance – Superbugs on the Rise

During his 1945 Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Alexander Fleming, who discovered penicillin, warned of the danger of an over-reliance on antibiotics and the threat of bacteria developing antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Antibiotics have been helping us fight infection since the 1940s. Before they were developed, even a small scratch could be fatal. Giving birth and having surgery were a lot riskier and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as syphilis and gonorrhoea, caused untold misery and could be a death sentence.

We now rely heavily on antibiotics to treat and prevent infection but what many people don’t realise is that they are also widely used in agriculture and aquaculture. The overuse of antibiotics in humans and animals has led to the emergence of multidrug-resistant “superbugs.” The UK government says: “As in humans, the sub-optimal use of antimicrobials in agriculture and veterinary practice contributes to the rise and spread of AMR all over the world.”3HM Government. 2019. Tackling antimicrobial resistance 2019-2024 – the UK’s five-year national action plan. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-5-year-action-plan-for-antimicrobial-resistance-2019-to-2024 [Accessed 1 June 2022].

Some types of bacteria that cause serious infections in humans have already developed resistance to most or all of the available treatments, and there are very few promising options in the research pipeline.4WHO. 2017. Stop using antibiotics in healthy animals to prevent the spread of antibiotic resistance. Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/07-11-2017-stop-using-antibiotics-in-healthy-animals-to-prevent-the-spread-of-antibiotic-resistance [Accessed 1 June 2022].

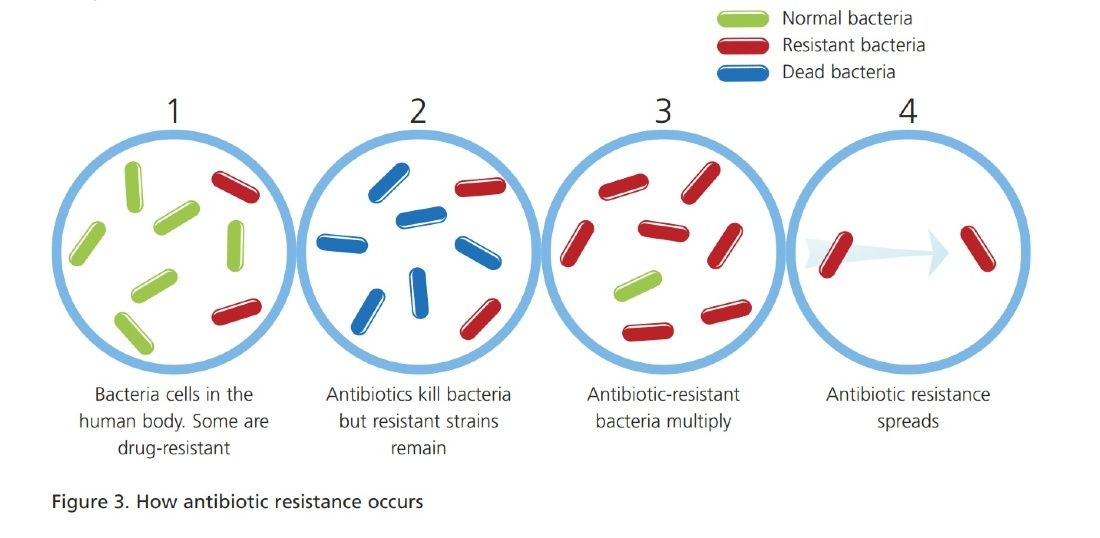

AMR happens because rapid and random DNA mutations occur naturally in bacteria – these may help them to prosper or have no effect. If a mutation helps a single bacterium survive antibiotic treatment while all the others die, that one will go on to reproduce, spreading and taking its new resistance gene with it like an accessory, enabling it to survive the hostile environment – the genetic equivalent of a stab-vest!

While the proper therapeutic use of antibiotics in animals is essential for treating infection, much of the use of antibiotics in livestock is not therapeutic. Soon after they were first introduced, it was found that antibiotics could promote growth when fed to farmed animals at low (sub-optimal) levels. This led to their widespread use and abuse to help fatten animals for the table. Antibiotic use in livestock now outweighs human consumption in many countries and in the US, for example, some 80 per cent of all antibiotics are used as growth supplements and to control infection in farmed animals.9Martin MJ, Thottathil SE, Newman TB. 2015. Antibiotics Overuse in Animal Agriculture: A Call to Action for Health Care Providers. American Journal of Public Health. 105 (12) 2409-2410.

Some countries have acted to reduce the use of antibiotics in livestock. In 2006, the European Union banned the use of antibiotics for growth promotion. However, mass medication of healthy animals is still used to prevent disease (metaphylaxis) when an infectious disease is present within the group, flock or herd.10Baptiste KE and Kyvsgaard NC. 2017. Do antimicrobial mass medications work? A systematic review and metaanalysis of randomised clinical trials investigating antimicrobial prophylaxis or metaphylaxis against naturally occurring bovine respiratory disease. Pathogens and Disease. 75 (7) ftx083. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) say that metaphylaxis is frequently used in intensively reared animals and that: “There should be an aim to phase out preventive use of antimicrobials, except in exceptional circumstances.”11EMA and EFSA. 2017. EMA and EFSA Joint Scientific Opinion on measures to reduce the need to use antimicrobial agents in animal husbandry in the European Union, and the resulting impacts on food safety. EFSA Journal. 15 (1) 4666.

Significant volumes of antibiotics continue to be used either prophylactically amongst healthy animals, to stop the development of an infection within a flock or herd, or simply for growth promotion, to speed up the pace at which animals gain weight. Both uses are particularly prevalent in intensive agriculture, where animals are kept in confined conditions.12O’Neill J. 2016. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. London, UK: review on antimicrobial resistance. 1-84. In 2017, the World Health Organisation recommended that farmers and the food industry stop using antibiotics routinely to promote growth and prevent disease in healthy farmed animals.2WHO. 2017. Stop using antibiotics in healthy animals to prevent the spread of antibiotic resistance. Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/07-11-2017-stop-using-antibiotics-in-healthy-animals-to-prevent-the-spread-of-antibiotic-resistance [Accessed 1 June 2022].

Factory farms are the most disease-ridden places on Earth. They are used to confine hundreds, sometimes thousands, of genetically identical animals with no access to outdoor space or natural light. This highly stressful, barren environment can lead to severe behavioural problems including repetitive and aggressive behaviour like cage biting, feather pecking and cannibalism. So, antibiotics are frequently used in such places to prop up this cruel and deeply flawed system of animal food production.

Antibiotic-resistant superbugs from factory farms can spread in manure sludge from the farm into the environment, contaminating surface water, groundwater and soil. From there, they may infect people swimming, drinking or washing with contaminated water or consuming contaminated crops.

People can also get infections from handling or eating meat, seafood, milk or eggs that are raw or undercooked and contaminated with resistant bacteria.15CDC. 2021. Antibiotic / Antimicrobial Resistance. Where Resistance Spreads: Food Supply. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/food.html [Accessed 1 June 2022]. In 2018, a UK Foods Standards Agency survey looking at chicken and pork for sale in Britain’s supermarkets found record levels of superbugs resistant to some of the strongest antibiotics.16FSA. 2018. Surveillance study of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria isolated from chicken and pork sampled on retail sale in the United Kingdom. Available: https://www.food.gov.uk/research/antimicrobial-resistance/surveillance-study-of-antimicrobial-resistance-in-uk-retail-chicken-and-pork [Accessed 1 June 2022]. A quarter of all chicken samples tested were infected with Campylobacter. Of these, almost half were resistant to ciprofloxacin and more than half to tetracycline. Multidrug resistance was found in 8.9 per cent of the Campylobacter coli from chicken. The official line is that the risk of acquiring AMR bacterial infections from foods is low provided that they are cooked and handled hygienically, but thousands of people are still infected with these food poisoning bugs every year.

There have been some improvements in the UK with antibiotic sales for use in animals falling by 35 per cent (six per cent in humans) between 2013 and 2017.19UK-VARSS. 2019. UK Veterinary Antibiotic Resistance and Sales Surveillance Report (UK-VARSS 2018). New Haw, Addlestone: Veterinary Medicines Directorate. In 2017, 36 per cent of antibiotics in the UK were sold for use in animals (the majority going to farmed animals with a smaller amount used in horses and companion animals), while 64 per cent were for human use (Veterinary Medicines Directorate, 2019). A lower proportion than in many other countries, but still a considerable amount weighing in at 226 tonnes in 2018.9UK-VARSS. 2019. UK Veterinary Antibiotic Resistance and Sales Surveillance Report (UK-VARSS 2018). New Haw, Addlestone: Veterinary Medicines Directorate.

However, the Advisory Committee on Antimicrobial Prescribing, Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infection (APRHAI), the expert scientific advisory committee providing independent advice to the Department of Health and Social Care, says that during the same period, the number of antibiotic-resistant bloodstream infections in the UK increased by 35 per cent and continues to rise.20APRHAI. 2019. APRHAI 9th annual report. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/aprhai-annual-report-2017-to-2018/aprhai-9th-annual-report [Accessed 1 June 2022]. It could be that the action being taken is too little, too late.

The World Health Organisation now says that AMR is one of the top ten global public health threats facing humanity.24WHO. 2020. Antimicrobial resistance. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance [Accessed 1 June 2022]. It could be the cause of the next pandemic the world faces. When antibiotics fail, chest infections, urinary tract infections (UTIs), cuts, insect bites and even small scratches can develop into sepsis (blood-poisoning) which can be fatal if not treated quickly. In the UK, five people die from sepsis every hour and the numbers are rising.25UK Sepsis Trust. 2020. About sepsis. Available: https://sepsistrust.org/about/about-sepsis/ [Accessed 1 June 2022]. The UK Sepsis Trust CEO, Dr Ron Daniels, says: “…nearly 40 per cent of E. coli – the bacteria that causes a huge number of infections – is now resistant to antibiotics and these organisms account for up to one third of episodes of sepsis, showing the vital need for responsible use of antimicrobial drugs.”26UK Sepsis Trust. 2020a. Sepsis and antimicrobial resistance. Available: https://sepsistrust.org/sepsis-andantimicrobial-resistance/ [Accessed 1 June 2022].

The idea of dying from a paper-cut or an insect bite is unthinkable but is fast becoming a possibility, thanks to the overuse and abuse of antibiotics. Professor Colin Garner, chief executive of Antibiotic Research UK, says:

“We have been warning for some time that our antibiotics are so ineffective that we could reach the situation where people will once again die from an infected scratch or bite. That tragic moment may just have come. I personally got bitten recently by a horsefly and it is very painful. I am self-medicating with creams and an oral antihistamine tablet to ensure the bite site does not become infected.”28Antibiotic Research UK. 2018. News Release: Horsefly bite death threat wings its way to Britain. Available: https://www.antibioticresearch.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Horsefly.pdf [Accessed 1 June 2022].

Across Europe alone, an estimated 25,000 people die each year because of hospital infections caused by the following five resistant bacteria:

- E. coli

- Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Enterococcus faecium

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)35Public Health England. 2015. Health matters: antimicrobial resistance. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-antimicrobial-resistance/health-matters-antimicrobial-resistance [Accessed 1 June 2022].

E. coli bloodstream infections are increasing in the UK and internationally. The number of infections that were voluntarily reported to Public Health England increased by 44 per cent between 2003 and 2011, and after the introduction of mandatory reporting in July 2011, a further 28 per cent increase was seen by July-September 2016.36Vihta KD, Stoesser N, Llewelyn MJ et al. 2018. Trends over time in Escherichia coli bloodstream infections, urinary tract infections, and antibiotic susceptibilities in Oxfordshire, UK, 1998-2016: a study of electronic health records. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 18 (10) 1138-1149. Between 2014 and 2018, the number of people affected in England rose from 53 to 70 per 100,000 population. An increasing trend in antibiotic resistance was also observed.37Public Health England. 2019. Laboratory surveillance of Escherichia coli bacteraemia in England, Wales and Northern Ireland: 2018. Laboratory surveillance of Escherichia coli bacteraemia in England, Wales and Northern Ireland: 2018 (publishing.service.gov.uk) Scientists suggest that E. coli bacteraemia rates have risen due to rising rates of antibiotic resistance.38Schlackow I, Stoesser N, Walker AS et al. 2012. Increasing incidence of Escherichia coli bacteraemia is driven by an increase in antibiotic-resistant isolates: electronic database study in Oxfordshire 1999-2011. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 67 (6) 1514- 1524.

Public Health England’s antimicrobial resistance (AMR) report, published at the start of World Antimicrobial Awareness Week in 2020, says that 21 out of every 100 people in England with bloodstream infections caused by a number of key bacteria are infected with antibiotic-resistant strains. This, they say, led to an estimated 65,000 antibiotic-resistant severe infections in 2019; equivalent to 178 new antibiotic-resistant infections per day.39Public Health England. 2020. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) data: 2018. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/escherichia-coli-e-coli-o157-annual-totals [Accessed 1 June 2022].

Some of these infections come from animals. Lord Jim O’Neill’s 2016 government-commissioned review on AMR describes the ways in which resistant bacteria in animals, created by the selective pressures of antibiotic use, could be transferred to humans. Transfer may occur, O’Neill says, through direct contact with animals, from undercooked or unpasteurised animal foods, or via the spread of resistant bacteria into environmental reservoirs, which may then transmit resistance genes to human bacteria, or come into contact with humans directly. Thus, explaining the link between the use of antibiotics in agriculture and resistant infections in humans. The report says: “In light of this information, we believe that there is sufficient evidence showing that the world needs to start curtailing the quantities of antimicrobials used in agriculture now.”6O’Neill J. 2016. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. London, UK: review on antimicrobial resistance. 1-84.

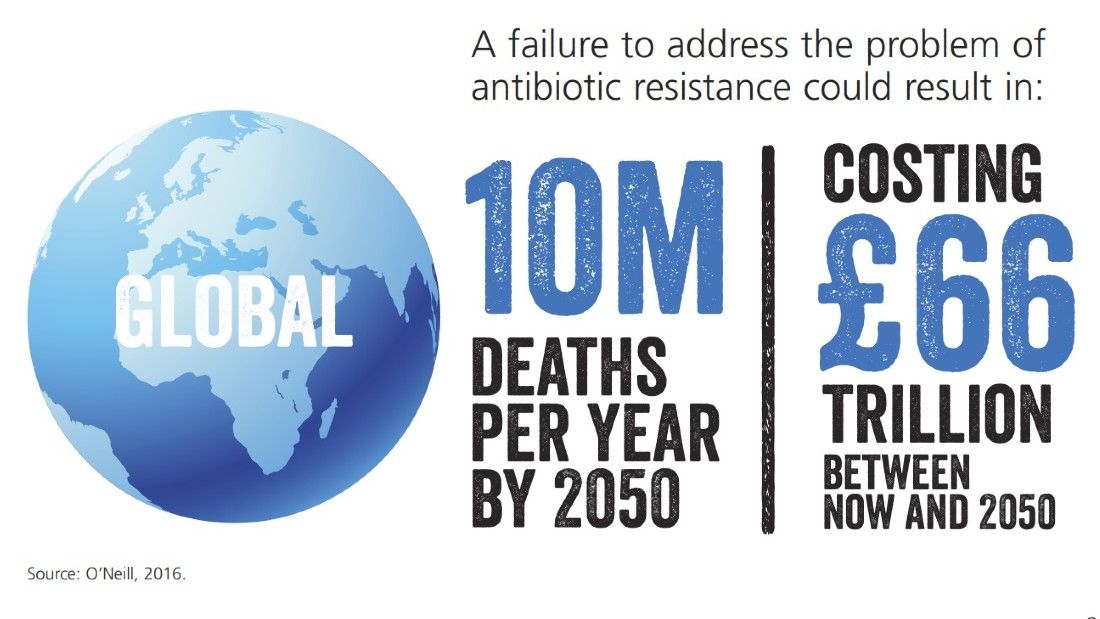

O’Neill warns that the 700,000 global deaths caused by AMR each year will rise to 10 million by 2050 if no action is taken. This would mean antibiotic-resistant superbugs killing more people than cancer. The cost in terms of lost global production between now and 2050 would be an enormous £66 trillion if no action is taken.6O’Neill J. 2016. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. London, UK: review on antimicrobial resistance. 1-84.

In July 2018, O’Neill became Chair of Chatham House, the international think tank. With the eyes of the press on him, he said that antibiotic resistance should be listed as a cause of death on official certificates to help raise awareness of the growing superbug crisis. O’Neill describes himself as a “resistance fighter” and says: “We need modern technology to discipline all seven billion of us to stop pressuring our medical practitioners to prescribe antibiotics when they aren’t necessary, and the food industry needs to stop fattening animals and fish with antibiotics, in order to permanently reduce our excessive dependence on the few drugs that work and the new ones we hope to have in the future. Because all of us need to be resistance fighters.”40Antimicrobial Resistance Fighter Coalition. 2021. Resistance Fighter’s story: I’m a resistance fighter. Available: https://antimicrobialresistancefighters.org/stories/story-lord-jim-o-neill [Accessed 1 June 2022].

Dr Kazuaki Miyagishima, Director of the Department of Food Safety and Zoonoses at the World Health Organisation, says: “Scientific evidence demonstrates that overuse of antibiotics in animals can contribute to the emergence of antibiotic resistance.” Miyagishima says: “The volume of antibiotics used in animals is continuing to increase worldwide, driven by a growing demand for foods of animal origin, often produced through intensive animal husbandry.”2WHO. 2017. Stop using antibiotics in healthy animals to prevent the spread of antibiotic resistance. Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/07-11-2017-stop-using-antibiotics-in-healthy-animals-to-prevent-the-spread-of-antibiotic-resistance [Accessed 1 June 2022].

Due to this increasing global demand for meat, it’s predicted that antibiotic use in cattle, chicken and pigs worldwide will increase by 67 per cent by 2030 and nearly double in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. This rise, scientists say, is likely to be driven by the growth in consumer demand for livestock products in middle-income countries and a shift to large-scale farms where antibiotics are used routinely.42Van Boeckel TP, Brower C, Gilbert M et al., 2015. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 112 (18) 5649-5654.

Colistin is regarded as a “last resort” antibiotic for humans but is still used widely in livestock, especially pigs, in some parts of the world. In 2015, bacteria carrying colistin-resistance genes were identified in China. The genes are carried in such a way that resistant bacteria are able to transfer them to different species of bacteria, something not seen before. This so-called ‘horizontal gene transfer’ rang alarm bells among the scientific community everywhere as it not only heralded the breach of the last group of antibiotics available to humans but opened up the possibility of AMR spreading even faster.48Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR et al. 2016. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 16 (2) 161-168.

Screening in areas of China, where colistin had been routinely given to pigs, revealed resistant E. coli in more than 20 per cent of animals, 15 per cent of raw meat samples and one per cent of hospital patients.22Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR et al. 2016. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 16 (2) 161-168. In Bangladesh, E. coli with resistance to colistin have been found in water, street food, hand rinse samples of street food vendors and healthy human gut samples. The authors of this study say that this is alarming and sheds light on the potential health risk that colistin-resistant E. coli could pose to millions of people.49Johura FT, Tasnim J, Barman I et al. 2020. Colistin-resistant Escherichia coli carrying mcr-1 in food, water, hand rinse, and healthy human gut in Bangladesh. Gut Pathology. 12, 5.

Colistin-resistant bacteria have now been identified in over 50 countries, including the UK.50Liu Y and Liu JH. 2018. Monitoring Colistin Resistance in Food Animals, An Urgent Threat. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 16(6) 443-446. The use of this antibiotic to treat infection in animals has since been voluntarily restricted by livestock industries in the UK, decreasing by 99 per cent between 2015 and 2017.51Veterinary Medicines Directorate. 2019. UK One Health Report – joint report on antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance, 2013-2017. New Haw, Addlestone: Veterinary Medicines Directorate. The EMA suggests that substances which are of last resort for treatment of life-threatening disease in humans should be excluded from veterinary use.52EMA. 2016. CVMP strategy on antimicrobials 2016-2020. Available: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/cvmp-strategy-antimicrobials-2016-2020_en.pdf [Accessed 1 June 2022].

It’s unclear why there hasn’t been a total ban on the use of this last resort antibiotic and the UK’s policy to accept voluntary initiatives and farm assurance schemes contrasts with other countries, such as Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands, where antibiotic use in animals is controlled through government legislation. China has now banned the use of colistin in animals as a growth promoter, falling in line with the EU, US, Brazil and, more recently, India. Scientists are unsure if this late action can curb the spread of resistance genes.

From January 2022, the EU banned the importation of all meat and dairy produced with antibiotic growth promoters, but it is still not clear whether the UK will implement this legislation too. The majority of meat and dairy imports in the UK come from the EU. However, the Government is keen to negotiate new trade deals with several countries, including the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. All four countries allow farmers to feed antibiotics routinely to livestock to make them grow faster (this practice is banned in the UK and the EU). In the US and Canada, for example, farm antibiotic use is about five times the level in the UK.55Alliance to Save Our Antibiotics. 2018. Government must ban all use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics in poultry as new FSA survey reveals record levels of resistance. Available: https://www.saveourantibiotics.org/news/press-release/government-must-ban-all-use-of-fluoroquinolone-antibiotics-in-poultry-as-new-fsa-survey-reveals-record-levels-of-resistance/ [Accessed 1 June 2022].

In their report Farm antibiotics and trade deals – could UK standards be undermined? The Alliance to Save Our Antibiotics says: “A failure to maintain and improve standards, coupled with a shift from importing EU-produced meat to importing cheaper meat from countries such as the US, Canada or Australia may have significant consequences for the levels of antibiotic resistance being spread via the food chain.”56Alliance to Save Our Antibiotics. 2020. Farm antibiotics and trade deals – could UK standards be undermined? Available: https://www.saveourantibiotics.org/media/1864/farm-antibiotics-and-trade-could-uk-standards-be-undermined-asoa-nov-2020.pdf [Accessed 1 June 2022]. This would be a huge step backwards!

The World Health Organisation says that AMR is one of the main threats to modern medicine, with growing numbers of infections, such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, gonorrhoea and salmonellosis becoming harder to treat: “Without urgent action, we are heading for a post-antibiotic era, in which common infections and minor injuries can once again kill.”11WHO. 2020. Antimicrobial resistance. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance [Accessed 1 June 2022].

There are stark parallels between the AMR crisis and climate change – both driven by the increasing global demand for cheap animal-based foods. The World Health Organisation talks about a ‘One Health’ solution because AMR does not recognise geographic or human-animal borders – we all share one planet.58WHO. 2017a. One health. Available: https://www.who.int/newsroom/q-a-detail/one-health [Accessed 1 June 2022]. The most effective way to tackle AMR and achieve optimal health for people, animals and our environment is to change the way we eat, reducing antibiotic use in humans and animals.

AMR is a problem of our own making – a direct consequence of the inappropriate use of antibiotics in humans and animals, in a drive to produce cheap meat, fish and dairy foods on an industrial scale. Failure to act may result in the chilling prospect of an apologetic doctor saying to you: “Sorry but there’s nothing we can do for you.”

The contribution to AMR from agriculture is significant and may be growing. Of course, livestock industries are inevitably resistant to change but the obvious solution is to stop producing animal-based foods and go vegan. The widespread adoption of a vegan diet would remove the factory farms that are the breeding grounds for these superbugs.