Lice-nsed to kill

Salmon and trout are held captive in underwater cages and doused with pesticides and antibiotics. Diseased, genetically weakened and stressed, they are a perfect captive meal for deadly parasites – sea lice.

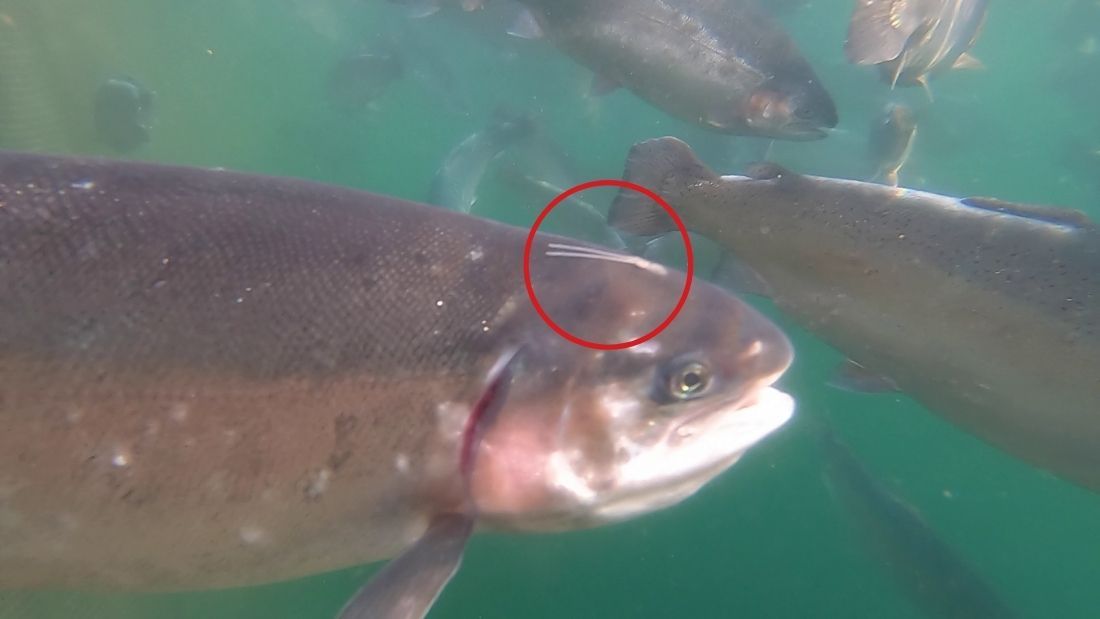

Lice attach themselves to unsuspecting fish to gorge on their skin and blood, eating them alive and wiping out entire fish farms. Even the use of deadly pesticides, multiple water treatments, and the introduction of cleaner fish, have failed to stop the rampant lice in their tracks. So persistent are they that some may still be hanging on to the prepared fish when you buy it.

See what the public had to say on our 2022 UK tour!

- Sea lice are ecto-parasitic copepod crustaceans that naturally occur in the marine environment

- They have exoskeletons – an external hard shell that supports and protects their bodies – and so to grow, they must shed this outer layer. In most cases females are bigger than males – an exception being the cod louse, Caligus curtus

- There are approximately 560 different species of sea lice

- They have been around for millions of years and have eight life stages; the first three are free-swimming, the next two are sessile (fixed in one place) and the final three are mobile – they attach themselves to a host in the third life stage

- Infective larvae are less than one millimetre long, which means finding a host in the wild is difficult; if the lice larvae cannot locate a host fish in time, they will die from starvation or predation

- Once attached to a fish host, they graze on their mucus, skin and blood – the Lepeophtheirus salmonis variety exclusively feed on salmonids such as Atlantic salmon, sea trout and Arctic char

- Adult females grow up to 12 millimetres in length (up to 29 mm including egg strings) and adult males, six millimetres

- Infestations of sea lice can cause physiological stress and significantly increase fish mortality rates

- They have a large ability to develop a tolerance to various treatments – particularly chemical-based where resistance to delousing compounds is a widespread problem

- Although mass mortality events caused by the parasites do happen outside of captivity, they are extremely rare in nature

Over the last 50 years, the global production of seafood has more than quadrupled, with the average person eating almost twice as much seafood as they did in the 1960s. Inevitably, wild fish populations have faced increasing pressure and nearly 90 per cent of the world’s fish ‘stocks’ (for which assessment information is available) are now reported as fully exploited, overexploited or depleted.

Yet overfishing – when more fish are caught than can be replaced through natural reproduction – is just one of the many threats the world’s oceans are facing. Habitat destruction, plastic waste, chemical pollution, ocean acidification, coral bleaching, oil drilling and global heating are all other major contenders that together equate in a bleak future for our marine wildlife. The idea of an inexhaustible ocean is a fallacy and the current rate of exploitation is completely unsustainable.

In response to the dwindling supply of ‘natural resources’ to meet the growing demand for seafood, the food industry has turned to modern farming practices for a solution. Aquaculture – the collective term used to refer to the farming of aquatic animals – is on the rise, rearing fish under controlled conditions for human consumption. It includes both salt and freshwater species and has become the world’s fastest-growing food production sector, generating over half the fish lining our supermarket shelves today.

Proponents of aquaculture argue that the rapid development of industrial fish farming eliminates the wasteful practice of catching, killing and throwing non-target fish species back out to sea (otherwise known as bycatch) and offers greater traceability in the food chain. But it will never be a cure-all and presents far more problems than it solves. The majority of farmed fish are carnivorous species and therefore rely on fishmeal and fish oil in their feed. Rather than alleviating pressure on wild fish populations, aquaculture instead helps increase it as wild fish are being caught to feed farmed fish! As with all industrial forms of farming, there are also huge animal welfare implications and other major consequences, creating a recipe for disaster.

Visit our fish page to read more.

Naturally, successful lice attach to salmonids whilst at sea. Since the lice cannot survive in fresh water, they generally fall off the adult fish as they return to their freshwater spawning streams. The problem for farmed salmonids, confined in filthy sea cages by their thousands, is that they’re unable to migrate to fresh water and are therefore unable to shed the lice without treatment (a range of which are outlined below).

Fish farms typically pack fish together in extremely high numbers to prioritise profit over welfare. This ultimately increases the density and occurrence of sea lice, creating a breeding reservoir that produces huge numbers of mobile juvenile sea lice, spoilt for choice in terms of finding a host fish. It’s a catastrophic direct consequence of the intensive aquaculture system.

In manufacturing the perfect environment for lice to rampantly reproduce, these factory farms lead fish to unnecessarily suffer from severe scale damage, reduced growth rates and a loss of their physical and microbial protective function as the lice graze on their skin, mucus and blood. The result is that farmed fish are increasingly susceptible to disease, secondary infection and premature death.

As if that isn’t bad enough, huge concentrations of sea lice also escape to the local marine environment and impact wild populations. A single salmon farm can increase the sea lice burden on migrating juvenile salmonids by as much as 73 times above normal levels. Clouds of lice will attach themselves to passing salmon and sea trout smolts, whose young fragile skin is not yet adapted to cope with infestations of parasites, and they are literally eaten alive. The lice can also be carried and spread to other wild fish, threatening the survival of entire species.

Frequent infestations of parasitic sea lice are devastating and widespread. Traditionally, the industry has relied on chemical feed additives that once ingested and absorbed into the fish’s tissues kill off the attached lice. These treatments have their own complications, however, as an abundance of waste feed is another inherent problem in aquaculture that negatively impacts the surrounding environment. Moult inhibitors for example halts the lice moulting cycle but cannot be used on a mass scale without altering the gene expressions of other crustaceans such as shrimp and lobsters.

Some treatments, like hydrogen peroxide, have also been linked to increased stress levels in Atlantic salmon, which is a significant welfare issue that cannot be ignored. By overusing such chemicals, the treatments are becoming less effective and have created growing concerns about drug-resistant sea lice – just as excessive antibiotic use in all forms of factory farming leads to antimicrobial resistance.

The search for alternative non-medicinal techniques for tackling sea lice outbreaks has been motivated by the growing market and opportunity for profit. These include lice skirts (tarpaulin sheets that are mounted around the top portion of fish cages that act as a shield), snorkels, laser pulses that detect lice on the fish and fire a short laser pulse at the louse and bubble curtains, as well as cleaner fish, fresh water flushing systems and thermal treatments.

There are several species of cleaner fish used in aquaculture – most commonly the lumpfish and ballan wrasse. Between 2010 and 2016 the commercial breeding programme for lumpfish escalated from thousands to well over 30 million. Generally, cleaner fish prefer to eat parasites in their later lifecycle stages, meaning that they are a more effective method of continuous delousing on farms already plagued with lice than a preventative measure to avert an outbreak.

In the winter, wrasse tend to become inactive whereas lumpfish continue to feed at low temperatures. They’re not immune to lice themselves either and can act as host fish – leading to increasing concerns over the welfare of cleaner fish and the notion that they may act as a vector for transmitting disease.

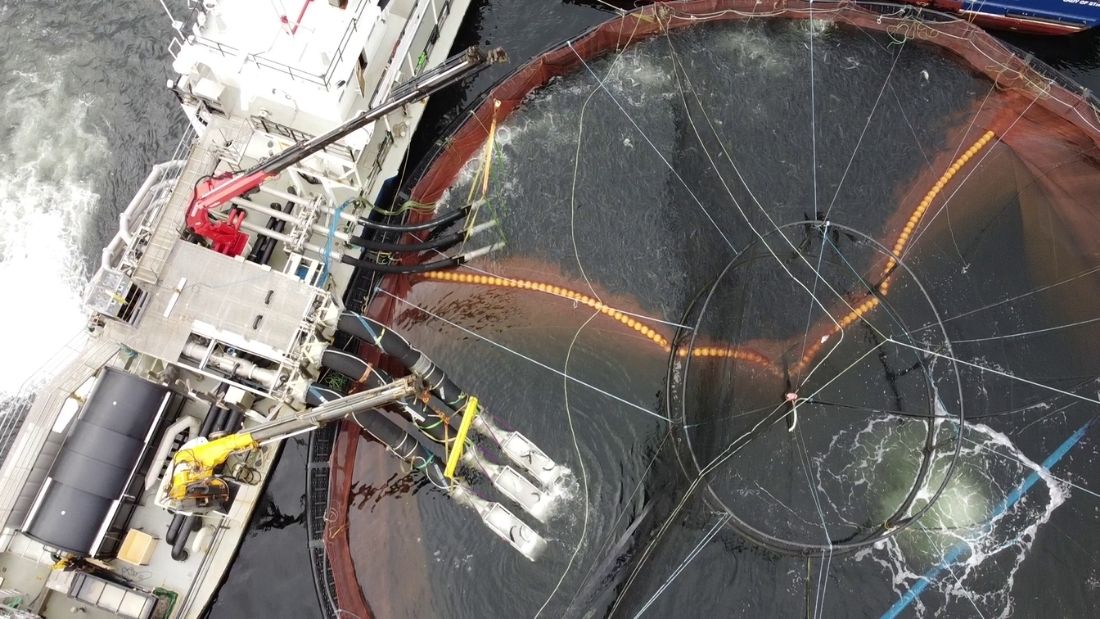

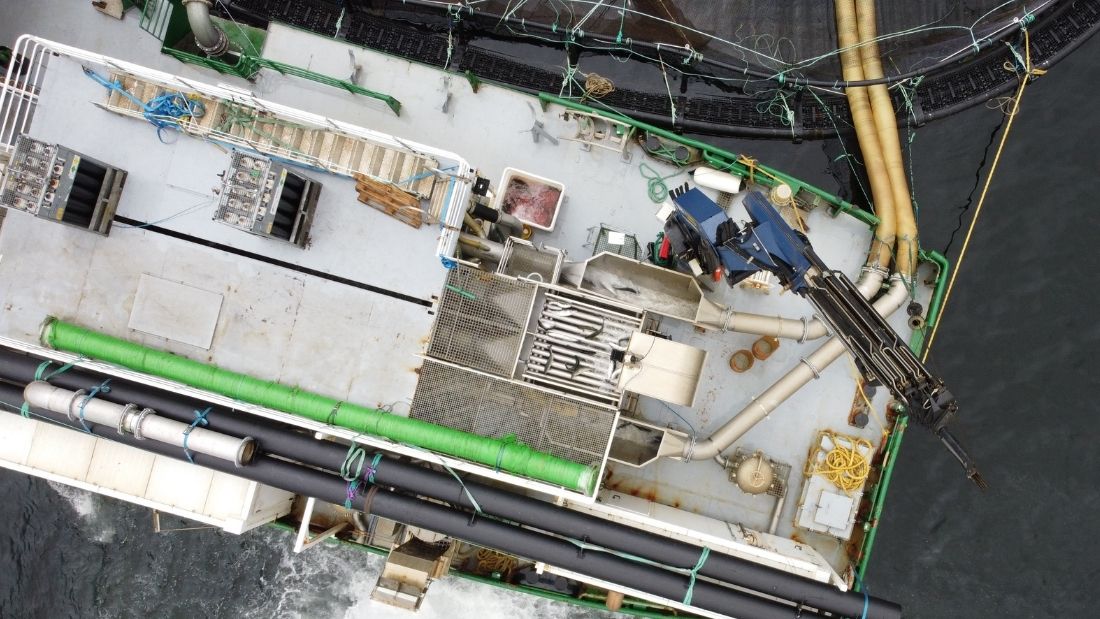

More recent technological developments for treating sea lice are called hydrolicers and optilicers or thermolicers. Both systems work by pumping the fish through a network of fresh water jets (hydrolicers) or passing them through heated water baths (optilicers and thermolicers) fitted to a boat or barge. Both treatments take advantage of the low tolerance sea lice have for fresh water or sudden changes in temperature. Once dislodged they are collected and destroyed.

These treatment processes are harsh and fish suffer from a range of injuries, heightened stress levels and death. According to the Scottish government, an average of 112,000 fish die every year in these devices and recent scientific research has also found that salmon exposed to water temperatures above 28 degrees Celsius behaved as if they were in pain – swimming faster, crashing into tank walls and shaking their heads.

More often than not, farmed fish undergo multiple lice treatments during their unnaturally short lifespans and fish for sale on supermarket counters have even been found with lice still attached. So, if you’ve always wanted to know what’s eating the fish you’re eating, the answer is parasitic sea lice.

Easy Vegan Swaps for Fish

End Factory Farming

Host a street action

Host a Lice-nsed to Kill stall of your own to warn fish-eaters they may be getting more than they bargained for when buying fish… a side of lice! Viva! will provide you with a complete stall pack full containing everything you need to run a successful event.

Door-drop our leaflet

V7 – Try Veganism for One Week

Switching from animal products to plant-based ingredients can have huge benefits for the planet, the animals and your health. That’s why we’ve launched V7 – our brand new ‘one week’ food challenge.

Vegan Recipe Club

Get inspired by hundreds of vegan recipe ideas with pictures, hints and tips for all different tastes and budgets