Farming for a vegan future – why?

The vegan movement is undoubtedly growing at a fast pace. Sainsbury’s Future of Food Report forecasts that, by 2025, vegans and vegetarians will make up a quarter of the UK population.

Much of the vegan campaign to date has centred around our food choices. Clearly though, veganism isn’t just about what we choose to consume, but also about what we choose to produce. In this regard, British agriculture is noticeably in need of a makeover!

Sadly, the relationship between farmers and vegans is tense. Farmers perceive vegans as a threat to their way of life. Vegans perceive farmers as people who remorselessly exploit animals.

The fact is, farmers will always be the people who produce our food, so a way to bridge this gap must be found.

At a conference hosted by the Farm Advisory Service in early 2020, the emphasis of the day was on diversification. It was pointed out to attendees that amidst chaos and disruption – from the climate crisis, our departure from the EU, and now Covid-19 – there is opportunity.

Change can be perceived as a threat or an opportunity. It’s important to remember that: “it’s not the strongest of the species that survives; nor the most intelligent; but the one most adaptable to change”.

Viva! Farming

We are at a crossroads as a species and our food and farming systems must change to meet the challenges ahead. Viva! Farming wants to transform our food system by helping farmers transition away from using animals in agriculture.

Visit the Viva! Farming website for more information.

To Protect Public Health

The Covid-19 pandemic has served to confirm something we already suspected – the food we produce and consume is killing us. As far back as 2004, the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, the World Health Organisation, and the World Organisation for Animal Health reported that our increasing demand for animal protein is one of the main risk factors of a pandemic. Flying in the face of that warning, we continued to increase production. Between 1961 and 2018, global meat production more than quadrupled.

What, exactly, is the connection between animal agriculture and a global pandemic such as the one we have just experienced and, according to experts, we should fully expect to experience again?

Covid-19, along with three out of four new or emerging infectious diseases, is a zoonotic disease meaning that it comes from an animal. Zoonotic diseases can be viral, bacterial, parasitic, or fungal. Often, the original host of the disease is a wild animal such as a bird, a bat, a pangolin, a badger, a chimpanzee, a rat or a deer.

Animal agriculture has brought us into close proximity with wild animals by destroying much of their natural habitats to create grazing land, to grow feed for farmed animals, or to construct concentrated animal feeding operations. Since 1960, animal agriculture has caused 65 per cent of global land-use change.

The natural world, that once formed a preventative barrier against disease, is rapidly shrinking. When nature is destroyed, the species that survive are those best at transmitting disease; for example: rats, bats, ticks, fleas, and mosquitos!

Zoonotic diseases are athletic and versatile! Many can jump directly from wild animals to humans either through the air or by direct or indirect contact – including exposure to their habitats. Others prefer to travel via an intermediary host. Because there are just so many of them around, farmed animals make perfect intermediary hosts. Of the six major zoonotic disease events that have impacted our country over the past one hundred years, the top three involved poultry, pigs, and cattle as intermediary hosts.

As our human population has increased, so has our demand for cheap animal products, causing a surge in the number of factory farms. Currently, there are 1,786 industrial-sized pig and poultry farms in the UK. These “intensive” farms house more than 40,000 birds or more than 2,000 fattening pigs. The largest UK mega farms hold 1.7 million and 1.4 million chickens respectively. Sadly, 84 per cent of all UK farmed animals are now housed in factory farms.

It is not just the cramped, unnatural, filthy conditions, and the stress that this causes the animals, that make factory farms a breeding ground for pandemics. The demand for higher and faster yields has resulted in huge numbers of genetically similar animals being housed together. Genetic diversity is a critical factor in disease resistance; its absence, known as the monoculture effect, adds to the animals’ susceptibility to disease.

The United Nations Environment Programme, in its investigation of emergent and neglected zoonotic diseases concludes: “logic and experience suggest that zoonoses can be best tackled through interventions involving the livestock hosts of the disease pathogens.”

We could not agree more! Given that we do not need to consume animal products, livestock-free farming is the best way to minimise the risk of a zoonotic pandemic.

Aside from the risk of zoonoses, there are many other health risks inherent in the production and consumption of animal products.

Although farm antibiotic use decreased by around fifty percent between 2014-2018, “last-resort” human antibiotics are still given to farm animals in the place of good husbandry.

Alarmingly, bacteria resistant to these life-saving antibiotics are now being discovered in raw meat and in farmed animals in disparate parts of the world. We are entering an era when, “many common infections will no longer have a cure and, once again, kill unabated”.

For more information on why an animal-based diet is “the number one killer of its consumers” see Viva! Health.

To Mitigate Climate Change

This year, a global threat to our survival upturned life-as-we-know-it: the Covid-19 pandemic. The virus, and its repercussions, temporarily overshadowed an even more devastating predicament: the climate crisis.

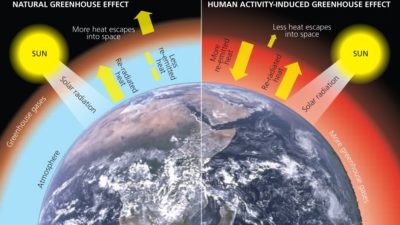

In 2018, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued a special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C degrees above pre-industrial levels, and potential mitigation measures. They found that a global shift to plant-based diets would reduce food’s greenhouse emissions by up to 70 per cent.

A comprehensive, independent study by Oxford University supported these findings. They surveyed almost 40,000 farms in 119 countries which represented approximately 90 per cent of everything we eat. They found that in countries with high meat consumption, shifting to diets that exclude animal products would reduce food’s greenhouse gas emissions by up to 73 per cent.

Interestingly, the researchers found that even the lowest-impact animal products caused more environmental harm than their vegetable protein substitutes.

A study published in IOPScience in 2017 found that, when analysed across five environmental factors (greenhouse gas emissions, land use, fossil fuel energy use, eutrophication-potential and acidification-potential), ruminant meat has impacts 20-100 times greater than plant-based foods. Dairy, eggs, pork, poultry, and seafood were found to have impacts 2-25 times higher than plants per kilocalorie of food produced.

In the UK, red meat, milk, and white meat, respectively, are the three highest food groups per capita in terms of the greenhouse gas emissions that they generate.

Clearly, if we are to reach our climate change mitigation goals, the shift to plant-based production and consumption is essential.

To Optimise Land Use for Planetary Health

Agriculture in Britain currently works against our planetary health goals. Between 2014 and 2019, greenhouse gas emissions from the sector failed to diminish. Without radical changes to how and what we farm, by 2030 animal agriculture is set to use almost half of the carbon budget permitted to keep us within a 1.5°C rise in temperature.

Conversely, farming in Britain also holds the lasting solution to meeting our climate change goals.

Currently, we do not use land well, neither for food production nor for environmental benefit. Almost half (48 per cent) of Britain’s total land area is used for animal agriculture. In arable areas, 55 per cent of UK cropland is used to grow animal feed. This is a waste of resources, perpetuates a cycle of environmental degradation, and, is completely unnecessary.

A 2019, ground-breaking study from Harvard Law School, showed that if all current UK cropland was used to grow crops for human consumption, we could more than provide for the calorific, protein and nutrient needs of the entire population.

This would mean that all UK grazing land (permanent pasture and rough grazing) could be released from animal agriculture and used for another purpose. The study shows that if all current grazing land (~84,000 km2) were to be restored to native forest cover, this would remove 3,236 million tonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere; the equivalent to offsetting nine years of total current UK emissions.

Trees are the most readily deployable method we have of removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and reaching our climate mitigation targets. When we shift to plant-based production, the vast amounts of land that will be released will mean that we can do this at scale.

To Restore Ecosystems and Biodiversity

It goes without saying that restoring native forest habitats would not only be a massive win for climate change mitigation, but also for ecosystems and biodiversity.

According to the Royal Forestry Society, woodland once covered most of our country. Today, just 2.4 per cent of the UK is ancient woodland with it’s rich, complex habitat that provides a home for more threatened species than any other habitat we have.

The Amazon rainforest has received a lot of attention for the devastating deforestation, mostly in the name of animal agriculture, that has taken place there. However, ancient woodland in the UK has been destroyed at an even faster rate than the Amazon; more than half of it has vanished in the past 80 years.

It’s not only woodland habitats that have been lost. Since World War II, 97 per cent of our wildflower meadows, 75 per cent of our ponds, 200,000 miles of hedgerows, 75 per cent of our heaths, and 98 per cent of lowland raised peat bogs have disappeared. This massive loss in habitat has led to the disappearance of 150 species in the UK in the past 100 years.

When ecosystems break down in this way, the planet’s life-support system, upon which we all depend, comes under threat. Habitat loss affects our very existence.

The image of England’s “green and pleasant land” with sheep grazing peacefully on hillsides may bring us a familiar comfort, but these iconic features signal a nature-depleted landscape. The climax vegetation of the UK– in other words, our indigenous vegetation that the land will regenerate to over time – is not pasture; it is trees, and all the wonderful flora and fauna that live amongst them. Lynx, wolf and wild boar once lived here, and beavers and cranes made their homes in our wetlands.

Conservationists believe that the next 30 years – the time for a tree to reach full maturity – will be crucial for biodiversity. Saving isolated pockets and fragments here and there is no longer enough, we have to see the big picture.

Ending animal agriculture would clear the main obstacle to rewilding Britain, permitting diverse habitats and species, including apex predators, to return thereby beginning to restore the natural balance of our life-giving ecosystems.

To Improve Food Security and Food Self-Sufficiency

There is adequate, existing cropland in the UK to provide for the calorific, protein and nutrient needs of our entire population. The problem is that we are currently using 55 per cent of that cropland to grow animal feed – a unnecessary and environmentally damaging waste of our natural resources. Using all UK cropland to grow food for human consumption would greatly augment our food self-sufficiency and our food security. With trade uncertainties due to our departure from the European Union, this becomes increasingly important.

Professor Tim Lang, the UK’s leading expert on food policy, points out that we have always expected someone else to feed us, which has made us dependent on an uncertain and fragile supply chain. By value, Britain imports more than 50 per cent of the food it consumes, including over 90 per cent of its fruit and veg.

Currently, only 2.8 per cent of UK cropland is used to grow fruit and vegetables. If we expand on this – even modestly – we can significantly increase food production. Take a crop such as strawberries that is grown widely in the UK. The amount of strawberries that could be produced on 1/100th of the cropland currently used to grow animal feed could provide 1.9 million adults their “5 a day” for an entire year; or 1.3 million, 2.4 million, and 2.1 million, respectively, for raspberries, apples and tomatoes.

It’s not just about fruits and veggies. It’s about expanding the potential of some of the other crops that we already grow – such as peas, beans, wheat and oats – and resurrecting some of the oldies – such as hemp – to feed us whilst cashing in on innovative and expanding markets. (See our section on Growing Crops for Human Consumption for more details.)

To Combat Sector Uncertainty

Changes in Subsidies

Making a living from farming is not easy at the best of times. Agriculture is an industry dependent on support. In England, 62 per cent of farm business income is from tax-payer supported subsidies; in Scotland, where farmers make an average loss of £14,600 from agricultural activities, subsidies form 84 per cent of farm business income.

Farmers who graze livestock (sheep and beef) make the biggest losses. In England, these losses average £18,650 a year (up to £21,500 in Less Favoured Areas); with Scottish farmers in Less Favoured Areas making estimated losses of £27,400 without support. These figures boost the case for ending unsustainable, uneconomic livestock farming and repurposing grazing land to meet our climate goals.

With Britain’s departure from the European Union, and the subsequent end of the Common Agriculture Policy, the future of farm subsidies is uncertain. Agricultural business advisors are recommending that farmers review what percentage of their income is from subsidy, and how low these subsidies could drop for their farm still to be viable and financial commitments met.

Surprisingly, the farmers who are thriving without support are those engaged in horticulture. Horticulturists (fruits, vegetables, nuts, herbs, flowers and ornamental plants) only derive around 8 per cent of their incomes from subsidies.

In other areas of farming, it is encouraging to see farmers increasingly taking their financial futures into their own hands. In both England and Scotland, revenue from diversification enterprises forms a significant part of farm income. In Scotland, farms that diversify beyond traditional agricultural practices have, on average, incomes around £19,600 a year higher than farms that don’t; in England the figure is £13,000. According to the NFU Mutual’s Diversification Report, 65 per cent of farmers in England have already diversified to the tune of £740 million in additional income in 2018-2019. (See our section on Starting Diversification Enterprises for more information.)

Our governments have said that future funding will support green initiatives and public payments will be awarded for public goods. Clearly, the time to move away from environmentally burdensome animal agriculture is here. Whether through growing crops for human consumption; farming carbon capture through native tree and ecosystem restoration; or diversifying into new ventures that support rural, green economies, the time to change is now!

Changes in Consumer Preferences

Subsidy uncertainty is not the only reason for farmers to shift to stock-free farming. Public preferences are changing. The number of vegans in Britain increased by 400 per cent from 2014 to 2019. A survey by supermarket giant, Waitrose, found that one in three Brits have stopped or reduced their meat consumption and Sainsbury’s Future of Food Report predicts that vegans and vegetarians will make up 25 per cent of the population by 2025.

It’s interesting that our large supermarket chains are performing these surveys. That tells us that they plan on changing their offerings to match changing consumer demands. Their supply chains, therefore, which include the farmers, must change too.

As we’ll see in our next section, many innovative farmers are already embracing these inevitable changes. At a Farm Advisory Service meeting in Scotland last year, one farmer with 45 acres of vegetables was heard to say, “I love vegans!”.

Advances in Biotechnology

New advances in biotechnology pose a further threat to the livestock sector. Independent think tank, RethinkX, describes an advancement in biotechnology that can create high quality protein from micro-organisms (fungi, algae, protozoa).

The report states that this protein will be superior to animal proteins in every way: “more nutritious, healthier, better tasting, and more convenient, with almost unimaginable variety”. By 2030, the report predicts that these proteins will be five times cheaper than existing animal proteins, causing a drop in demand for beef and dairy by fifty percent, with other livestock markets following suit.

The technology known as precision fermentation will mean that “anywhere we can brew beer, we can make food” – independent of climate, geography and topography. Which means that cheap, high quality, local, nutritious food would be available to everyone.

Simply put, they are predicting the collapse of the livestock industry. The time to get out is NOW!