Deforestation

Forests are diverse and dynamic places, hosting a quarter of the world’s biodiversity. As well as being stunningly beautiful, they are vital for the health of our planet. Known as the ‘lungs of the world’, forests take carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and release oxygen back into it – we are losing forests at our peril! Animal agriculture is the biggest driver of deforestation as forests are cleared to make way for growing animal feed and grazing. We need to protect the world’s forests now more than ever and going vegan is the best way to stop this unnecessary destruction.

Forests cover almost a third (31%) of the global land area and are home to most of Earth’s terrestrial biodiversity.1FAO and UNEP. 2020. The State of the World’s Forests 2020. Forests, biodiversity and people. Rome. http://www.fao.org/state-of-forests/2020/en/ From fungi and insects, to tigers and elephants; more than half the world’s land-based plant and animal species, and three-quarters of all bird species, live in and around forests. They influence rainfall patterns, water and soil quality and help prevent floods.2WWF. 2020. Why forests matter. https://www.wwf.org.uk/learn/effects-of/deforestation

Trees, like all green plants, absorb and store carbon from the air. During photosynthesis they use energy from the sun to turn the carbon from carbon dioxide into building blocks for their trunks, branches and foliage and they release oxygen back into the atmosphere. When trees are cut down and burned or left to rot, their stored carbon is released into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. This is how deforestation and forest degradation contribute to the climate crisis. If we stand any chance of protecting the planet from global warming, we have to stop deforestation.

People have been converting forests into agricultural land for thousands of years as populations and the demand for food have grown. From 1750 until the late 19th century, most land use changes involved deforestation in temperate regions between the tropics and the Polar Regions. Temperate means moderate and in these regions, the average yearly temperatures are not extreme – neither really hot nor freezing cold. Here, forests and woodlands were cleared to make room for fields and pastures.

In more recent times, deforestation has been greatest in the tropics, where the temperature remains relatively hot throughout the year. For example, during the 1980s and 1990s, rainforests were the primary source for new agricultural land, with more than 80% of it coming from intact and disturbed forests.3Gibbs HK, Ruesch AS, Achard F et al. 2010. Tropical forests were the primary sources of new agricultural land in the 1980s and 1990s. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (38) 16732-16737. Forest disturbances occur when the structure or composition of a forest ecosystem has been disrupted.

Agricultural expansion remains the biggest driver of deforestation and forest degradation. The IPPC says that agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) is responsible for just under a quarter of all anthropogenic (caused by human activity) greenhouse emissions; this is mainly from deforestation and agricultural emissions from livestock, soil and nutrient management.4Smith P, Bustamante M, Ahammad H et al. 2014: Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use (AFOLU). In: Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Edenhofer O, Pichs-Madruga R, Sokona Y et al. (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ipcc_wg3_ar5_chapter11.pdf

Between 2015 and 2020, the rate of deforestation was estimated at 10 million hectares per year, down from 16 million in the 1990s. One hectare is about the size of a European football field or Trafalgar Square in London – imagine an area 10 million times that size! Large-scale commercial agriculture – mainly cattle ranching and cultivation of soya bean and oil palm – accounted for 40% of tropical deforestation between 2000 and 2010, and local subsistence agriculture for a further 33%.1FAO and UNEP. 2020. The State of the World’s Forests 2020. Forests, biodiversity and people. Rome. http://www.fao.org/state-of-forests/2020/en/

The global rate of deforestation may have slowed in the last decade, but it remains alarmingly high in many parts of the world. In Europe, North America and Northeast Asia, some gains in forest land have been achieved along with reductions in agricultural land. However, imports of animal foods have increased; so we have simply moved the problem elsewhere. This is known as ‘carbon leakage’ as it does not reduce global emissions.

Brazilian Beef

Brazil is the world’s second-largest beef producer, after the US, and the world’s largest exporter of beef, providing around 20% of total global beef exports.1USDA. 2019. Brazil once again becomes the world’s largest beef exporter. https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2019/july/brazil-once-again-becomes-the-world-s-largest-beef-exporter/

Before Jair Bolsonaro became Brazil’s president in 2019, previous governments had taken steps to reduce deforestation. But, during his 2019 to 2022 term, Bolsonaro’s administration weakened environmental agencies, cut enforcement, rolled back protections and undermined Indigenous land rights to expand agriculture.

Since taking office in January 2023, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has made strides in reversing the environmental policies of his predecessor and aims to end deforestation by 2030 but rising fires and political challenges make the situation uncertain.

Unlike boreal forests, where fires are a natural part of the ecosystem, fires in humid tropical forests such as the Amazon are very rare and almost entirely human-caused. Many of the fires there are caused by deforestation, through slash-and-burn techniques which involve setting fires to clear land for cattle ranches or to grow animal feed. These fires damage biodiversity, disrupt rainfall cycles and contribute to global climate change, creating a vicious cycle of degradation and warming.

The Amazon is being lost at a frightening pace, with fires, drought and illegal activity driving the damage. According to the World Resources Institute, in 2024, the Amazon biome experienced the most loss since 2016, jumping 110 per cent from 2023 to 2024. Huge areas of forest were destroyed, mostly because of massive fires made worse by extreme drought. For the first time, fire – not logging – was the main cause of forest loss.

Then in 2025, things got even worse; in the first half of the year, forest destruction jumped by more than a quarter compared to 2024 and in May alone it nearly doubled. Much of this is happening because of illegal land clearing for agricultural expansion and the fact that the forest, weakened by drought, is now even more vulnerable to burning.

Satellite images show that deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest has increased rapidly; the National Institute for Space Research (INPE), say deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon has surged above three football fields a minute, pushing the world’s biggest rainforest closer to a tipping point beyond which it cannot recover.2INPE. 2019. Area detection variation of DETER project with monthly granularity and PRODES Annual Seasonality (August to July). http://terrabrasilis.dpi.inpe.br/app/dashboard/alerts/legal/amazon/aggregated/ Brazil contains 60 per cent of the Amazon rainforest.

Dr Erika Berenguer, from the University of Oxford, says that clearing land for beef production is the biggest driver of deforestation; not producing timber or making space to produce palm oil or soya beans. Berenguer says: “Typically, gangs use a chain slung between two tractors to knock down trees quickly and at an industrial scale. Once the felled trees are dry enough, they are burned to leave the ground clear for cattle ranching.”3Vaughan A. 2019. Deforestation in Brazil has rocketed since Bolsonaro became president. www.newscientist.com/article/2210621-deforestation-in-brazil-has-rocketed-since-bolsonaro-became-president/#ixzz5vvN2WZay

The previous omission of land use change in estimates of greenhouse gas emissions and carbon footprints from food production, has led to serious underestimates; particularly for meat and especially for beef. For example, a study looking at the carbon footprint of beef produced on newly deforested land in the area of the Amazon Basin known as Amazônia Legal (Legal Amazon), where expansion of cattle ranching for beef production is a major cause of deforestation, estimated it at more than 700 kg carbon dioxide equivalents per kilogram of carcass weight. This is substantially higher, by several orders of magnitude in some cases, than figures for beef production on established pasture on non-deforested land.4Cederberg C, Persson UM, Neovius K et al. 2011. Including carbon emissions from deforestation in the carbon footprint of Brazilian beef. Environmental Science and Technology. 45 (5) 1773-1779.

Increased production for export has been the key driver of the pasture expansion and deforestation in the Amazônia Legal region during the past decade and this should be reflected in the carbon footprint attributed to beef exports. Carbon footprints must include the effects of land use changes to avoid giving misleading information to policy makers, retailers and consumers.4Cederberg C, Persson UM, Neovius K et al. 2011. Including carbon emissions from deforestation in the carbon footprint of Brazilian beef. Environmental Science and Technology. 45 (5) 1773-1779.

Slash-and-burn

In their natural state, tropical rainforests rarely burn, because of the moist conditions under the canopy and because dry lightning (without rain) is rare. Land-clearing methods, such as slash-and-burn, compound these effects by directly releasing greenhouse gases into the air. Slash-and-burn agriculture involves cutting and burning a forest to create a field. Widespread deforestation aided by fire has occurred in parts of the world where forests have been removed permanently for industrial-scale crop production. Fire-driven deforestation is the main source of carbon emissions in the Amazon.5van Marle MJE, Field RD, Werf GR et al. 2017. Fire and deforestation dynamics in Amazonia (1973-2014). Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 31 (1) 24-38.

There is widespread interest in better-understanding the greenhouse gas emissions and carbon footprint of different foods. The main purpose of estimating these is to provide information for policy-making, for supply chain management and to facilitate a shift by retailers and consumers toward low-carbon products.4Cederberg C, Persson UM, Neovius K et al. 2011. Including carbon emissions from deforestation in the carbon footprint of Brazilian beef. Environmental Science and Technology. 45 (5) 1773-1779.

“…deforestation is not a precondition for supplying the world with sufficient food in terms of quantity and quality in 2050.”6Erb KH, Lauk C, Kastner T et al. 2016. Exploring the biophysical option space for feeding the world without deforestation. Nature Communications. 7, 11382.

Around a fifth of global cropland was dedicated to export production in the 2000s. In some countries of South America and Southeast Asia, production for export markets makes up a substantial share of the total agricultural output. For example, Indonesia and Malaysia alone produce over 90% of all palm oil consumed in the world and Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil and Paraguay together account for nearly all the soya bean and over 80% of beef exports from Latin America.7Henders S, Persson UM and Kastner T. 2015. Trading forests: land-use change and carbon emissions embodied in production and exports of forest-risk commodities. Environmental Research Letters. 10 (12) 125012.

How environmentally friendly is your beef burger?

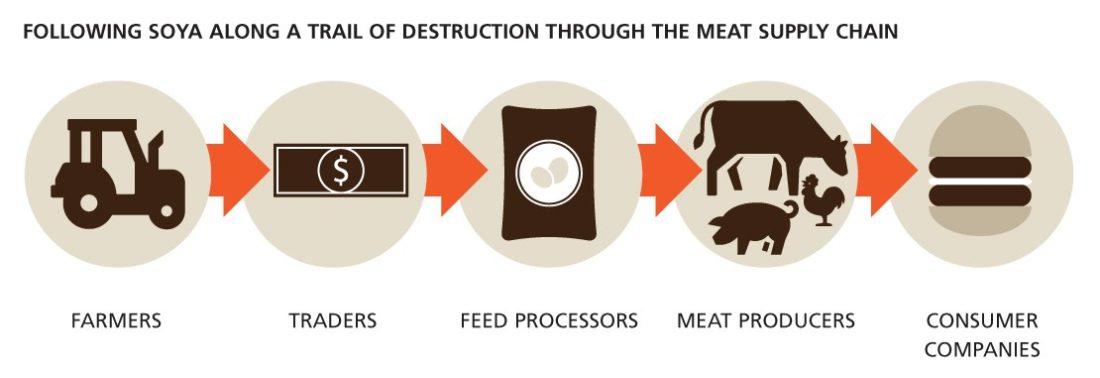

While many products are driving deforestation today, all of them take a back seat to beef – the biggest deforestation driver of tropical forests and also number one globally. Most of the soya grown on farms in Latin America is used for animal feed to fuel the supply of fast food consumed around the world. However, there is little traceability, so the strong links between a burger eaten in London or Manchester, for example, and Amazonian deforestation are lost.

Mystery meat

Early in 2017, the campaign groups Mighty Earth and Rainforest Foundation Norway released the Mystery Meat report showing how the hamburger chain, Burger King, was keeping the origins of its meat supply secret. Through remote sensing, supply chain investigation, drone videos and field visits to 29 plantations across 3,000 kilometres of jaguar and sloth habitat in Brazil and Bolivia, the report revealed Burger King and its suppliers’ massive contribution to rainforest destruction.8Bellantonio M, Hurowitz G, Leifsdatter et al. 2017. The Ultimate Mystery Meat, Exposing the Secrets behind Burger King and Global Meat Production. www.mightyearth.org/mysterymeat

In response to the very public campaign, in June 2017, Burger King released new environmental commitments, setting a goal of eliminating deforestation by 2030.9Restaurant Brands International. 2016. 2016 Sustainability Report. www.rbi.com/interactive/newlookandfeel/4591210/2016sustainabilityreport.pdf However, some environmental activists say this is nothing more than a marketing ploy – or ‘greenwashing’ – to build up an eco-friendly appearance.

Vegan for the forests

The more animal-based foods we eat, the more endangered our forests become. Changing our diets could have a phenomenal impact on reducing world hunger and deforestation. Researchers from the Institute of Social Ecology in Vienna published a study in Nature Communications revealing that it is possible to produce enough food for the world in 2050, while maintaining the current forests of the world – that means zero deforestation. They looked at a range of dietary scenarios including diets rich in meat, reduced meat, vegetarian, vegan and organic diets. They found that if the world went vegan, in 2050 we would require less cropland than we did in 2000. In other words, if the whole world becomes vegan, the projected global population in 2050 (over nine billion) could eat enough without another single tree being cut down.1Erb KH, Lauk C, Kastner T et al. 2016. Exploring the biophysical option space for feeding the world without deforestation. Nature Communications. 7, 11382.

A vegan diet, they said, is associated with only half the cropland demand, grazing intensity and overall biomass harvest of comparable meat-based diets. Furthermore, reducing the consumption of animal-based foods is also associated with major health benefits, particularly in the industrialised regions of the world.1Erb KH, Lauk C, Kastner T et al. 2016. Exploring the biophysical option space for feeding the world without deforestation. Nature Communications. 7, 11382.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is an intergovernmental economic organisation with 35 member countries. Most OECD members are high-income economies regarded as developed countries. Modelling in the WWF’s Living Forests Report suggests that meat consumption in OECD countries must be halved by 2050 if we are going to achieve zero deforestation and forest degradation.2WWF. 2014. The Growth of Soy: Impacts and Solutions. WWF International, Gland, Switzerland.

The greenhouse gas mitigation from dietary change increases substantially once the land-saving effects are taken into account. If we all went vegan and the land used previously for grazing animals was allowed to revert to forest, the resulting carbon sequestration in vegetation stocks (carbon being captured and held in plants and soil) could be large enough to cancel out 300 years of all food-related greenhouse gas emissions.3Bryngelsson D, Wirsenius S, Hedenus F et al. 2016. How can the EU climate targets be met? A combined analysis of technological and demand-side changes in food and agriculture. Food Policy. 59, 152-164.

The recent coronavirus pandemic adds another layer of concern to the loss of our forests. More than 28,000 different plant species are used in medicines and many of them come from forests. Yet, forests also pose health risks. Forest-associated diseases include malaria, Chagas disease, African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), leishmaniasis, Lyme disease, HIV and Ebola.4FAO and UNEP. 2020. The State of the World’s Forests 2020. Forests, biodiversity and people. Rome. http://www.fao.org/state-of-forests/2020/en/ The majority of new infectious diseases, including Covid-19, are zoonotic – they come from animals, and their emergence may be linked to habitat loss and increased human exposure to wildlife as human activity encroaches into forests.

Planting the seeds of change

We need to change our diets to halt deforestation and the loss of biodiversity. “We must move away from the current situation where the demand for food is resulting in inappropriate agricultural practices that drive large-scale conversion of forests to agricultural production and the loss of forest-related biodiversity” according to the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations. They say: “Adopting agroforestry and sustainable production practices, restoring the productivity of degraded agricultural lands, embracing healthier diets and reducing food loss and waste are all actions that urgently need to be scaled up.“4FAO and UNEP. 2020. The State of the World’s Forests 2020. Forests, biodiversity and people. Rome. http://www.fao.org/state-of-forests/2020/en/

There is no question that global demand for animal-based foods will continue to rise unless we actively promote changing our diet to move away from these products. There is a clear need for a strategic, integrated approach to agriculture, forestry and other policies linked to how we use the planet’s natural resources.5FAO. 2016. The State of the World’s Forests 2016. Forests and agriculture: land-use challenges and opportunities. Rome. http://www.fao.org/publications/sofo/2016/en/