Diet and cancer

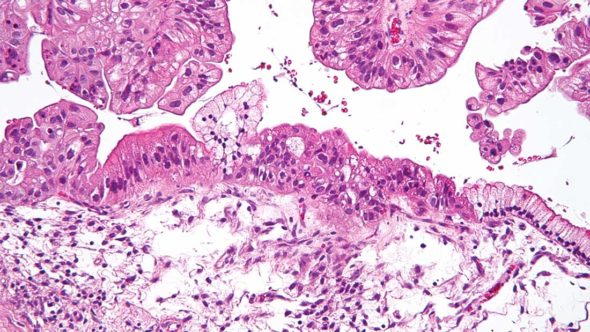

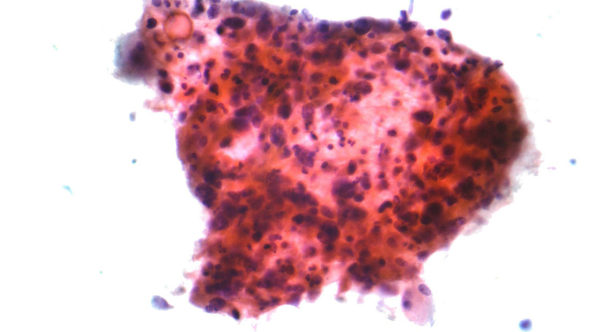

Cancer refers to a collection of diseases where abnormal cells divide in an uncontrolled way, which can lead to the formation of tumours. Sometimes cancer can spread to other parts of the body, and cause cancer there too.

Cancer is a major threat to our health today but diet and lifestyle can significantly reduce or increase the risk of cancer in general and even more so for some types of cancer. In the UK, the lifetime risk of cancer has been on the rise for decades. The lifetime risk of cancer in the UK increased from 38.5 per cent for men born in 1930 to 53.5 per cent for men born in 1960. For women it increased from 36.7 to 47.5 per cent (Ahmad et al. , 2015). For people born since 1960, the risk is 50 per cent. This means over half of people who are currently adults under the age of 65 years will be diagnosed with cancer at some point in their lifetime. Intimidating as this sounds, there are volumes of scientific studies showing a diet change can achieve a lot in terms of both prevention and treatment of cancer. There are thousands of studies linking diet to cancer so the below is a careful selection outlining the bigger picture. For latest news and updates, see our Nutrition News on cancer.

World Cancer Research Fund and The American Institute for Cancer Research (2009) outline the most important preventable causes of cancer as:

- Smoking

- Unhealthy diets

- Physical inactivity

- Excess body weight

The report states that “the prevention of cancer is now one of the most important, achievable and potentially rewarding global public health challenges”. It goes on to say that diets high in plant foods, and specifically non-starchy vegetables, fruits and other foods high in dietary fibre, vitamin C and carotenoids can protect against a number of cancers.

The report of World Cancer Research Fund and The American Institute for Cancer Research preceding the above document (2007) takes an in-depth look at diet, lifestyle and all relevant factors important in cancer prevention. One of the report’s main recommendations is for people to eat mostly foods of plant origin, non-starchy vegetables (green leafy vegetables, cucumbers, peppers) and fruit consumption to be at least 600 grams daily (at least five portions) and wholegrains and/or pulses to be a part of every meal.

Here is a selection of studies that have investigated the role of plant foods in preventing cancer:

- A recent study by Oxford University, looking at how diet affects cancer risk, revealed that vegans have a much lower risk of getting the disease (Key et al., 2014). The 15-year-long study followed 60,000 British men and women, of which over 18,000 were vegetarians and 2,246 vegan. They found that overall cancer incidence (compared to meat-eaters) was 11 per cent lower in vegetarians and 19 per cent lower in vegans. This result corresponds with a review by Huang et al. (2012) that reached the conclusion that vegetarians (all groups of vegetarians together) have 18 per cent lower cancer rates than meat-eaters.

- Another large study of almost 70,000 people, their dietary patterns and cancer incidence suggests that vegan diets are associated with a lower risk of all cancers combined and particularly with lower risk of female-specific cancers when compared with non-vegetarians (Tantamango-Bartley et al., 2013). Vegetarians as a combined group had lower risk of all cancers and gastrointestinal cancers in particular than meat-eaters.

- The well-known Cornell-Oxford-China Study, ‘The China Study’, conducted in 1970s and 1980s demonstrated important relationships between dietary patterns and cancer risk (Campbell and Junshi, 1994). The study involved 65 Chinese counties and focused on their diets and health. Campbell and Junshi reported that several major diseases such as brain, breast, colon and lung cancer, leukemia, cardiovascular disease and diabetes were all associated with affluent diets. In other words, these diseases were directly associated with the intake of milk, meat, eggs, animal fat and protein whilst diets high in fibre, antioxidants (mainly from fruit and vegetables) and pulses seemed to have a preventative effect.

- Authors of a comprehensive review of studies on cancer and diet (Lanou and Svenson, 2010) agree that diets rich in plant foods decrease the risk of many types of cancer. They point out that specific beneficial effects have been shown for fibre, fruits and vegetables, pulses including soya foods, seeds, spices and wholegrains.

- Abdull Razis and Noor (2013) decided to investigate more closely why broccoli and other cruciferous species appear to have a strong preventative effect against many types of cancer (mostly colorectal, lung, prostate and breast). Cruciferous vegetables contain substantial amounts of glucosinolates, a class of sulphur-containing glycosides, and their breakdown products such as the isothiocyanates are believed to be responsible for their health benefits. This study found that both glucosinolates and isothiocyanates can modulate the activity of enzymes that are crucial for cancer-prevention.

- Bosetti et al. (2012) analysed data from a series of studies from Italy and Switzerland and found that consumption of cruciferous vegetables at least once a week significantly reduced the risk of cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx, esophagus, colon and rectum, breast and kidney.

There are vast numbers of studies showing the association between animal products and cancer; here is a small selection:

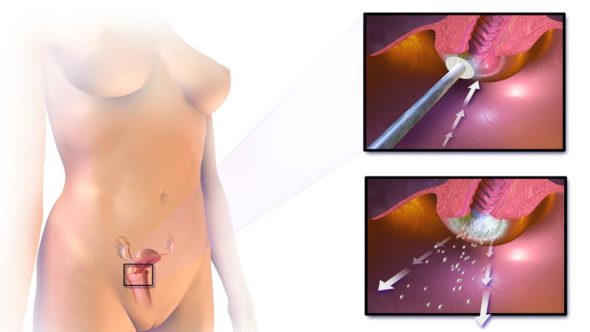

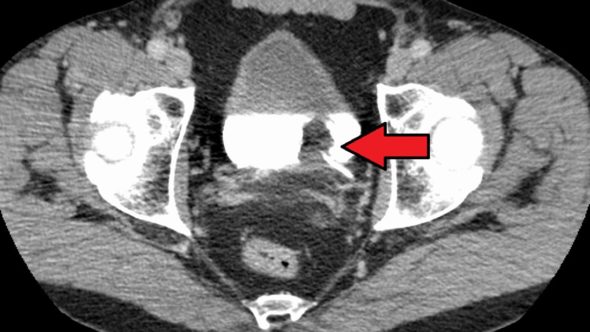

- Grant (2013) undertook a comprehensive study and analysed data from 87 countries to examine the relationship between lifestyle and cancer. The results showed that the main factor contributing to 12 types of cancer across the countries was animal product consumption (which included meat, milk, fish and eggs). The types of cancer that animal products were most strongly linked to were breast, uterus, kidney, ovarian, pancreatic, prostate, testicular and thyroid cancer and multiple myeloma. The study also documented how the rise of animal product consumption in some countries was followed by increased cancer rates. Examples of this include colon cancer rising after 15-27 years and breast cancer after 20-31 years in Japan, and mortality rates for some cancers in several Southeast Asian countries increased 10 years after meat and dairy consumption rose. The author explained that animal product consumption causes increased production of insulin, insulin-like growth factor 1 and sex hormones in the body which is probably why it’s so strongly linked to cancer. Higher levels of these hormones are known to increase the cancer risk for several organ systems. Grant also pointed out that haem-iron found only meat may be a risk factor for cancer through increased production of free radicals and DNA damage. Furthermore, higher protein intake has been shown to stimulate cancer promoting reactions in the body and it was suggested that the only diet that could avoid these is a wholesome vegan diet excluding protein isolates.

- The World Health Organisation (WHO), based on extensive research by its advisory body – The International Agency for Research on Cancer – recently classified processed meat as carcinogenic and red meat as probably carcinogenic (Bouvard et al., 2015).

- It’s been known for a long time that cooking meat at high temperatures produces carcinogenic compounds called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) and heterocyclic amines. A recent study revealed that these compounds increase their carcinogenic potential when they chemically interact with nitrogen (a basic element in protein) and become nitrated (Jariyasopit et al., 2014). The study showed nitrated PAHs have 6 to 432 times higher potential to cause mutations, that can lead to cancer, than the parent compounds. High-temperature cooking of meat therefore poses a much bigger health risk than previously thought.

- The most abundant of heterocyclic amines, a compound called PhiP, also has strong estrogenic effects and has been linked to hormone-sensitive cancers (Papaioannou et al., 2014). Some substances added to processed meat, such as nitrites used as preservatives, can also lead to the formation of carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds and these, together with an increased presence of PAHs (due to high temperature processing) and high content of haem-iron, might be the reason why processed meat has been shown to be more carcinogenic than red meat.

- Another factor increasing the potential of animal-based foods to contribute to cancer are environmental pollutants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). Although these industrial compounds were banned worldwide more than 30 years ago because of their high toxicity, they are very persistent and therefore still present in our environment. Once in the body, PCBs accumulate in the fat tissue and can cause long-term problems such as compromised immune response, mental and behavioural problems, decreased activity of the thyroid, reproductive problems, can induce cancer and severely damage the development of a baby. A review published in the journal Environmental Medicine revealed that in the food chain fish, dairy, hamburgers and poultry are the most contaminated foods (Crinnion, 2011).

For references and more information, see The Incredible Vegan Health report or visit Nutrition News for latest studies on diet and health.