Almonds and avocados – the plight of the honeybee

Vegans don’t eat honey because it’s not ours to take, bees make it to feed themselves during the winter. While almonds and avocados are plant foods and are therefore considered vegan, there is an ethical issue linking these foods and bees.

In 2018, the host of the TV programme IQ, Sandy Toksvig, asked panellists which of the plant foods they were being shown – avocados, almonds, melon, kiwis and squash – were NOT vegan. She then told them that none of them were vegan because their cultivation depends on the unnatural use of commercially farmed honeybees. It fast became another argument to use against vegans, showing how apparently hypocritical and flawed we are, even though most almonds and avocados are eaten by non-vegans and not all almonds and avocados are grown using bees in this way – more on that later.

Even though a vegan diet is undisputedly the best diet for animals, the environment and our health, the anti-vegan rhetoric continues. It’s a classic case of propaganda, where there may be some truth in a story, but the wider and more important issues are completely ignored. Piers Morgan, for example, never misses the opportunity to drag this one up as he did in 2023 when he interviewed Viva!’s founder Juliet Gellatley, she wasn’t having any of his nonsense! So, if you too want to know how to counter this argument or are concerned about bees and want to know how best to protect them, read on…

While most staples we eat (eg maize, wheat, rice, potatoes, cassava, peas and lentils) don’t need pollination, three-quarters of global crops depend on pollinators such as bees, flies, beetles, butterflies and moths, as well as birds and small mammals. Lots of fruit and vegetables, oil crops, coffee, nuts and avocados rely on them to some extent and a few crops, such as Brazil nuts, kiwi fruit, melons and cocoa beans, are fully dependent on pollinators.

In the US, for example, honeybees are used to pollinate over 100 different crops (roughly $15 billion worth) each year from almonds to zucchini (courgette). Around one-third of the food eaten by Americans comes from crops pollinated by honeybees including apples, melons, cranberries, pumpkins, cucumbers, squash, broccoli, almonds and avocados to name just a few. Many of these crops are visited by a combination of wild bees and managed bees. Pumpkin, cherry and apple, for example, tend to be visited more by wild bees than managed bees, while almonds, especially those grown in large-scale Californian orchards, may receive few if any visits from wild bees. Smaller almond farms, surrounded by natural habitat, however, do receive visits from wild bees and this is seen in watermelon and blueberry too.

Some crops are now grown in such vast monocultures that natural pollination is difficult if not impossible, so honeybee colonies are transported across the country for ‘pollination services’. They have been bred, in much the same way as other farmed animals, to optimise their production of honey, but as vast extensive monocultures have grown, renting bees out to pollinate them has become a lucrative sideline. Not only is it harmful to the bees, but this destructive practice also disrupts biodiversity.

Dr Juan González-Varo, from The University of Cambridge’s Zoology Department, says: “Honeybees are artificially bred agricultural animals similar to livestock such as pigs and cows. Except this livestock can roam beyond any enclosures to disrupt local ecosystems through competition and disease.” In other words, commercially farmed bees used to pollinate large monocultures are destroying the surrounding natural ecosystems and contributing to the loss of native pollinators.

Almonds and bees

California produces more than 80 per cent of the world’s almonds with most being produced in intensive industrial systems, planted in huge monocultures, using large amounts of water for irrigation, as well as millions of litres of pesticides. These huge monocultures are simply too big for wild bees to pollinate naturally, so growers rely on ‘managed’ honeybees for pollination, renting out more than one million colonies of bees from commercial beekeepers from all over the US every season. This makes the pollination of California’s almonds the largest annual managed pollination event in the world according to the non-profit Bee Informed Partnership.

Since the early 2000s, almond production in the US has increased and it is now the largest specialty crop concentrated almost entirely in California’s arid Central Valley, the orchards cover a region more than four times the size of Greater London. During this time, the number of commercial hives in the US has remained at around three million colonies.

During the almond pollination season, more than 70 per cent of commercial honeybee colonies in the US are used to pollinate orchards, which now provide as much revenue for beekeepers as honey production. In early spring, bees are loaded onto trucks and transported from around the US cross-country to California’s almond farms increasing the risk of exposure to harmful viruses, fungi such as the gut fungus (Nosema ceranea) and parasites such as the Varroa mite (Varroa destructor). These mites latch onto honeybees and suck their ‘fat body’ tissue, stunting and weakening them and potentially causing entire colonies to collapse.

Pesticides

Honeybees that complete the long journey across US states to pollinate almond trees are often exposed to high levels of fungicides, pesticides and lethal combinations of them. Neonicotinoid pesticides (or neonics for short) are a group of systemic insecticides that threaten bees and general biodiversity. Unlike contact pesticides, which remain on the surface of plants (eg leaves), systemic pesticides are absorbed and transported throughout the plant to the leaves, flowers, roots and stems as well as pollen and nectar. They act by binding to specific receptors widely distributed in the central nervous system of some insects including bees, causing overstimulation, paralysis and death. The Wildlife Trusts say that a single teaspoon of neonicotinoid is enough to deliver a lethal dose to 1.25 billion bees. Honeybees exposed to sub-lethal levels may experience problems with flight and navigation, impaired taste and slower learning, which all impact foraging ability and hive productivity. They may not be able to find their way home!

To make matters, worse, when they eat a restricted diet, as bees are forced to do so on industrialised monocrops, they are 50 per cent more likely to die as a result of neonicotinoid exposure. This is likely due to their poor nutritional status given the complete lack of wild habitat.

A 2023 assessment by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) predicts that the three most commonly-used neonicotinoid insecticides are likely to jeopardise over 200 threatened and endangered species, including pollinators like the rusty patched bumble bee, Hine’s emerald dragonfly and the Karner blue butterfly. Research also suggests problems for human health, one study suggests that about half of the US general population will have recently been exposed to neonicotinoids. Recent studies suggest potential toxic effects to humans and other vertebrates could include cytotoxicity (cell death), genotoxicity (damaging genetic information in cells causing mutations that may lead to cancer), reproductive effects, neurotoxicity (nerve damage), immunotoxicity (leading to higher levels of infectious disease or cancer), hepatotoxicity (liver damage) and hepatocarcinogenicity (liver cancer). It’s a scary list!

Banned in the UK and EU

The UK and EU banned the outdoor use of several neonicotinoids in 2018 to protect pollinators. However, for the fourth year running, in 2024, the UK Government granted emergency authorisation for the use of a neonicotinoid pesticide called Thiamethoxam on sugar beet, disregarding evidence on the devastating impact on bees. This was welcomed by the sugar beet sector but criticised by environmental campaigners – emergency authorisation of this bee-killing pesticide is a “deathblow”, say The Wildlife Trusts. In the US these pesticides remain on the market, although some states restrict their use.

Undernourished

Forcing bees to collect pollen and nectar from vast monocrops deprives them of the nutritious and diverse pollen and nectar provided by wild habitats. Continually moving colonies around the country also forces them to experience feast and famine situations, whereby they arrive during a ‘boom time’ but when the particular crop has bloomed, there are no other foraging opportunities unless they scavenge from wild plants which deprives native pollinators.

After the almond season, the bees may be taken to cherry, plum and avocado orchards in California or apple and cherry orchards in Washington State. In summertime, they may be transported east to fields of alfalfa (largely used for animal feed), sunflowers and clover in North and South Dakota or to squashes in Texas, clementines and tangerines in Florida, cranberries in Wisconsin and blueberries in Michigan and Maine. Along the east coast they are used to pollinate apples, cherries, pumpkins, cranberries and various vegetables.

By November, beekeepers begin moving colonies to warmer places to wait out the winter. According to IFIS (previously the International Food Information Service), US beekeepers are splitting hives up to make up for lost numbers over winter, using mail-order queens for new hives and feeding bees on corn syrup or ‘pollen patties’ – a simulated pollen substance – to help repopulate hives in the dead of winter, when bees are supposed to be clustering around the queen and keeping her warm.

In 2019, a Guardian report estimated that 50 billion bees died in the US during the winter of 2018 to 2019 – more than one-third of commercial bee colonies. Taken together, research shows that honeybees are facing a lethal combination of stressors including parasites, mites, pathogens, disease, a lack of healthy and diverse pollen resources and exposure to bee-toxic pesticides. These commercial honeybees have little status and are considered ‘livestock’ by the US Department of Agriculture because of their use in food production and suffer the same mistreatment as other farmed animals.

It’s clear that in the US, bees are being exploited on a huge scale, in much the same way as chickens, pigs and cows – being farmed in ever-increasing numbers on mega-farms, to feed ever-rising demands, with no thought for the animals nor the environmental impacts of such intensive practices. “The bees in the almond groves are being exploited and disrespected,” says Patrick Pynes, an organic beekeeper who teaches environmental studies at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff. “They are in severe decline because our human relationship to them has become so destructive.” If you don’t want to be a part of this, don’t buy Californian almonds.

Spanish almonds

Spain is the world’s second largest producer of almonds, producing 365,210 tonnes of almonds (with shells) in 2020 compared to the US’s 2.2 million tonnes. A very different scenario to the Californian one is found whereby a large part of the almond crop is organic and rainfed (without irrigation).

That’s not to say honeybees aren’t used at all for pollination services in Spain, it does happen albeit on a much smaller scale. That said, people are looking for solutions and Professor María José Rubio-Cabetas, from the Centro de Investigación y Tecnología Agroalimentaria (CITA) in Aragón said that 50 years ago, CITA were already considering the problems of some almond varieties and the lack of bees to pollinate them. At that time, she said, they began finding late flowering self-fertilising varieties which were made available to producers as they did not require bees. Self-pollinating almond trees are also being developed in the US too and have produced significant amounts of almonds. However, they are not quite there yet as the presence of bees has been found to increase yields further.

The Spanish Almond Board-Almendrave (SAB-Almendrave), a group of almond and hazelnut exporters says, “In Spain, crops are more respectful of bees and the biodiversity of the environment, given the variety of crops that coexist combined with large areas of forest”. The Importaco Terra company, established in 2015, aims to promote sustainable almond agriculture in Spain and teaches farmers how to employ practices that respect the indigenous fauna, the responsible use of insecticides and the protection of habitats in cultivated land.

On a more general conservation note, “The European almond is the perfect example of low-impact agriculture,” says Pere Ferré, president of SAB-Almendrave. “It uses water responsibly, thanks to the fact that 85 per cent of the farms are dry land, and those that are irrigated increasingly opt for on-demand irrigation; and the almost 800,000 hectares of this tree planted on the Peninsula capture a huge amount of carbon, contributing decisively to combating climate change, in addition to acting as a natural firebreak and tool against soil erosion.”

A grower’s association called AlVelAl is building a movement in the Altiplano region in the Southeast of Spain where ninety-five per cent of crops only use rainwater. The project is led by regenerative agriculture and its producers hope to transform almond monocultures into biodiverse productive ecosystems. It is located in the largest area of almond cultivation in Spain that includes the Altiplano de Granada, Los Veléz, Alto Almanzora, Guadix and the Northeast of Murcia. These regenerative farms, they say, are creating a mosaic ecosystem with ecological corridors that serve as a natural barrier against desertification in southeastern Spain. Both honeybees and wild pollinators are integrated into this agroforestry system, which either indirectly, attracted by aromatic plants and flowers, or directly, installing hives between the tree lines, benefit pollination and live happily with an abundance of food. “A totally different scenario from that of bees in California,” they say, “severely punished and at risk due to industrial production.”

For vegans, this may still amount to exploitation as some of the bees are not naturally present and have been bought in to ‘work’ for humans. But as awareness of the plight of the honeybee grows, it seems likely that some producers may move over entirely to producing ‘bee-friendly’ almonds and avocados that do not use commercial honeybees at all.

IFIS says if you still want to buy almond milk, look for the brands which have a bee-friendly certificate and promote organic almond produce. In the EU, for example, Alpro say their almonds are sourced in the Mediterranean region, mainly rainfed and that they are collaborating with their suppliers to identify and promote pollinator-friendly products and production systems that will be applied to all their almonds by 2025. If you feel like almond milk is not for you, there are plenty of environmentally friendly plant-based alternatives such as oat or soya milk.

Avocados and bees

Mexico is the world’s biggest avocado producer accounting for around 28 per cent of global production, other major producers are Colombia, Peru, Indonesia and Dominican Republic. The US, produces less than two per cent of global production. Many different insects visit avocado flowers in these countries, from bees and wasps to flies and beetles. In fact, wild insects are the most abundant pollinators in many regions and it’s suggested that developing practices that make the most of their contribution would be the best approach. This means avoiding extensive monocultures and avoiding the use of pesticides (especially neonicotinoid pesticides which are associated with mass bee deaths).

In Mexico and Cuba numbers of wild pollinators are higher than in other countries and native species (eg stingless bees and flies) are as effective as honeybees at avocado pollination. However, land clearance and deforestation in what has become known as Michoacán’s ‘Avocado Belt’ in Mexico is a serious concern.

In the US, around 90 per cent of avocados are grown in California where some 60 species of insects are attracted to the flowers and about half of them are native bees; the rest are mostly flies and wasps. Native pollinators include the ultra-green sweat bee (Agapostemon texanus), especially common during the avocado flowering season, flying quickly from flower to flower. Another fan is the yellow-faced bumblebee (Bombus vosnesenskii), one of the most common bumblebees in California. Then there are small carpenter bees (Ceratina species), which along with hoverflies are some of the most common native pollinators of avocados (Syrphidae). However, with native bee populations declining, American avocado farmers have turned to migratory beekeeping to fill the gap. Sadly, honeybees don’t find avocado flowers so attractive but have little choice if their hives are placed in a large orchard with no other flowers to choose from.

Some avocado producers in Spain, which is not far behind the US in terms of production, say that in well-sustained, non-specialised rural areas, the naturally occurring population of wild bees and other pollinators are sufficient to pollinate crops. So, the picture appears very varied from country to country.

The situation in the UK

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) says paid contracts to bee farmers for pollination services to field and orchard crops are rare in the UK compared with the situation in the US where it is a large industry. In 2010, it was estimated that around two per cent of UK hives (around 5,700) were professionally managed for pollination services. In 2017, among both professional and amateur beekeepers, the majority said they primarily kept bees for honey production while five per cent kept hives for pollination services. Taken together, honeybees only pollinate between five to 15 per cent of the UK’s insect pollinated crops, with wild bees pollinating between 85 to 95 per cent of the rest.

Water use

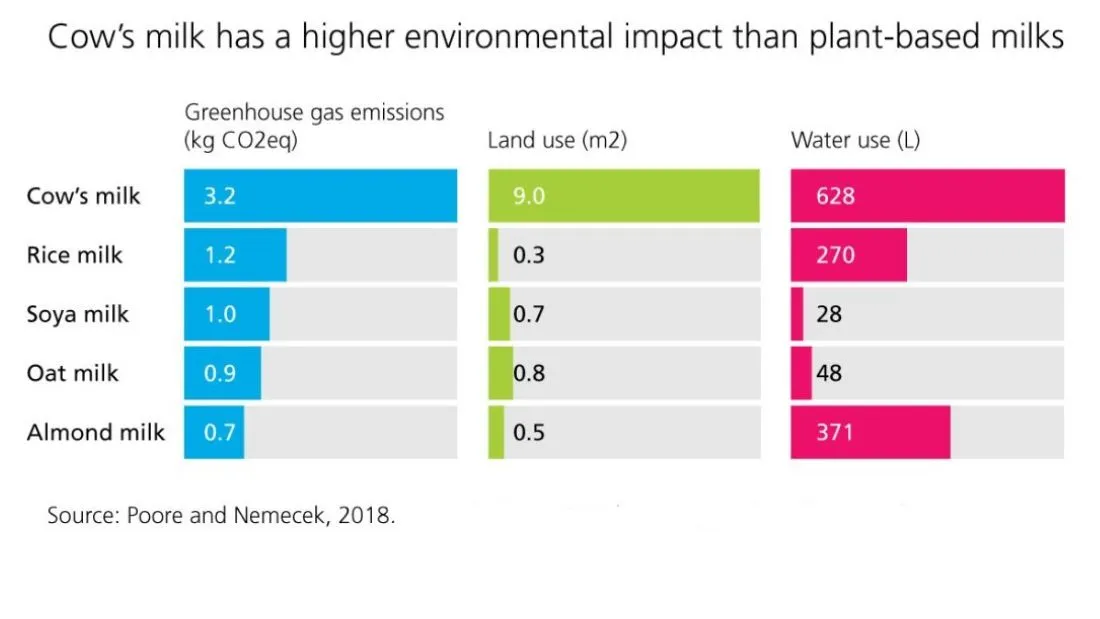

It’s often said that almond milk should be avoided because of the large amount of water required to produce almonds but as with other environmental issues, the cow in the room goes unnoticed. Almond milk requires 74 litres of water for a single 200-millilitre glass, while this is considerably more than oat or soya milk, filling that same glass with cow’s milk would require 126 litres of water.

The dairy and beef industries’ drain on water resources in California is frequently overlooked. “Almonds are made out to be the villain in our drought story, but blaming excessive water use on this crop is simply not true,” says local environmental activist Mohan Gurunathan in California’s Mercury News. “In fact, the water used to grow just animal feed – not including water to grow and slaughter them — uses more than double the water used to grow almonds and pistachios.”

Non-profit Food & Water Watch estimates that it takes 142 million gallons of water a day to maintain the 1.7 million cows living on mega-dairy farms in California. But the amount the animals drink is far exceeded by the billions of gallons a year required to irrigate pastureland and water-intensive feed crops such as alfalfa that are fed to animals in the US and exported to China and other countries. As Bloomberg columnist Justin Fox says, cows suck up more water than almonds!

Food miles

Avocados and almonds have been blamed not only for using up too much water but also for being transported across vast distances making them less environmentally friendly than locally sourced animal foods. This is simply not true, it’s much more important what you eat than where your food comes from. Many of the foods people assume to come by air are actually transported by boat – avocados and almonds are prime examples according to senior researcher at the University of Oxford, Dr Hannah Richie. Avocados, for example, are harvested unripe and transported in containers by ship and shipping one kilogram of avocados from Mexico to the UK generates just eight per cent of their total carbon footprint, according to Ritchie. Almonds have an even longer shelf life and don’t need to be flown either.

Insect apocalypse!

UK flying insect populations have declined by as much as 60 per cent in the last 20 years. The global picture is similar with over 40 per cent of the world’s insects in decline having lost their natural habitat to intensive agriculture. The main drivers of these catastrophic losses are; the expansion of industrial animal agriculture including growing animal feed, habitat loss, deforestation, increased pesticide use and climate change. In the UK, insects are moving north at an average rate of two kilometres a year due to increased temperatures from climate change and animal agriculture produces a fifth of all greenhouse gas emissions thus contributing substantially to global heating.

Animal feed

Many crops grown for animal feed need pollinating, including alfalfa (aka lucerne), for example, which is widely grown throughout the world as forage for cattle. In the US, large numbers of leafcutter bees (40,000 to 60,000 per acre) are used to pollinate alfalfa which is used for feed within the beef and dairy industries. It’s ironic that an argument used against vegans consuming almonds and almond milk often comes from someone who drinks cow’s milk produced by animals fed crops pollinated by, you guessed it, commercially farmed bees. Of course, for meat-eaters, the exploitation of bees may not be a concern – but it should be as a mass decline in bee populations, that has already begun, could cause a chain reaction that will become catastrophic as plants and the animals that eat them disappear.

Conclusion

Being vegan reduces animal suffering more than any other diet. It also reduces the environmental impacts of food production and offers many health benefits. Most vegans will have experienced some form of questioning or criticism; if you try to do the right thing, it seems you leave yourself open to criticism for not being perfect! We all make a personal choice when we shop and vegans try to choose foods that have the least impact. For avocados, consider having them just as an occasional treat and opt for organic, responsibly sourced ones if you can. If you live in Europe, you can source avocados from Spain, the only country in Europe to export them, meaning they will have a smaller carbon footprint and should be more regulated under EU law (eg for pesticide use). For almonds, you can buy Spanish almonds instead of Californian ones, opt for organic in order to look out for bees, and use only as an occasional treat.

Last word

Veganism is best understood as a philosophy and way of life which seeks to minimise animal exploitation – in a world consumed by it – as far as is possible and practicable. Remind yourself, as a vegan, you play no part in intensively farming animals, in slaughter, in the decimation of the oceans, or in the number one cause of wildlife extinctions – the consumption of meat, fish and dairy. Being vegan is the best way to create a more sustainable food system that offers wild pollinators the best chance too. It’s a win-win for us, the environment and the bees.