Dairy – bad for animals and the planet

It still surprises many to hear that in order to produce milk an animal first needs to be pregnant – it’s one of the dairy industry’s biggest misconceptions and it’s a perpetual cycle of suffering!

To meet the demands of modern high yielding dairy farming we push Britain’s farmed animals to the limit.

There are many common questions about the dairy industry as we simply aren’t told the truth and are brought up with a false idea of what dairy farming is.

We have summarised the main ones:

Cows only produce milk when they have given birth to a calf and, in nature, they would only produce as much as the calf needs and when the calf is weaned, milk production stops. Even when they are milked at a farm every day, the amount of milk they produce gradually decreases so they are impregnated every year to keep the milk flowing.

For more information, click here.

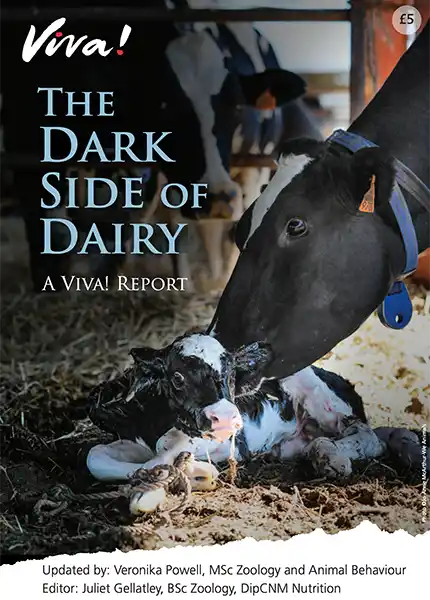

As stated above, cows only produce milk when they have given birth to a calf. In order for humans to have cow’s milk, her calf has to be taken from her shortly after birth so they don’t drink the milk the farmer can sell. Calves are placed in individual stalls or pens (hutches) at just a few hours old and fed an artificial milk replacer or surplus milk. Both mother and calf suffer immense stress as a result and call for each other for days. This is a far cry from what happens in nature.

For more information, click here.

Some people claim that most of the land used for grazing animals would not be suitable for growing crops and therefore it’s better to use it for animals to graze on. However, an increasing number of dairy cows are continuously housed in zero grazing systems and never go outside, so this argument is becoming weaker as farming methods intensify.

Land used for grazing animals can become damaged by their hooves compacting the soil, making it harder for plants to grow. However, it’s a reversible process and it would be entirely possible to cultivate such land. Land that can’t be used for crops would be suitable for growing trees that could provide fruit and nuts. This would bring many benefits to the environment (eg trees store carbon, prevent soil erosion, increase the water-retention capacity of land and improve air quality).

A 2019 Harvard Law School study found that if all UK cropland was used to grow crops for humans to eat, rather than feeding crops to animals, we could produce more than enough protein and calories for the entire population. This would mean that all UK grazing land could be repurposed and if restored to native forest, this would offset nine years’ worth of current UK emissions.

A cow would naturally suckle her calf for nine months to a year, but calves born on dairy farms are taken away from their mothers within a few days of birth – often after just a few hours. A strong mother-infant bond is formed between a cow and her calf immediately after birth and the separation is extremely traumatic for both.

The calves are then placed in individual pens or hutches and fed a commercial milk replacer, either from an artificial teat or a bucket. Occasionally, they get surplus milk or milk that would be refused from milk processing due to hygiene reasons.

Young calves are very susceptible to disease. Diarrhoea (known as scours in the farming sector), often caused by low-quality or incorrectly prepared milk replacer and subsequent malnutrition and dehydration, is the main cause of calf death. To reduce the risks, dairy calves are weaned on to solid food by five weeks of age – much sooner than is natural for them.

Under welfare regulations, calves may be housed in individual stalls or hutches (indoors or outdoors) until they are eight weeks old. Legally, calves must be removed from the hutches and group-housed by no later than eight weeks of age. Viva! have filmed calves up to 12 weeks old still isolated in violation of the law.

Individual housing denies calves vital exercise and social contact. Group housing allows more natural social behaviour but also increases the risk of airborne diseases such as pneumonia – the most common disease of weaned calves. Essentially, it is impossible to artificially rear calves, away from their mothers, in a way which fulfils their natural needs and behaviours without compromising their health.

Female calves will eventually enter the dairy herd, replacing worn-out cows, being forcibly impregnated for the first time when they’re only 13-20 months old.

Male calves are of little use to a dairy farmer. Like female calves, bull calves are removed from their mothers shortly after birth, housed in stalls or hutches and fed milk replacer. It used to be common practice for farmers to shoot bull calves at birth, but due to bad publicity major supermarkets and dairy processors have banned it. The use of sexed-semen is on the rise to reduce the number of male calves born, but others are sold on to beef farms through livestock markets or raised for veal. They spend most of their short lives – usually between six months and one year – confined in buildings and yards. High mortality rates in these systems are common as it is not financially worthwhile for farmers to treat illnesses.

In 2015, industry figures stated 95,000 newborn male calves were shot on-farm and was later deemed ‘dairy’s dirty secret’. More recently, in 2020, an AHDB report estimated around 60,000 male calves were killed on-farm every year – which is about 15 per cent of all bull calves born on dairy farms. Viva! filmed the shocking fate of the male calves at farms supplying milk for the confectionery giant Cadbury. For more information and footage, click here.

According to Red Tractor, by 2023 95 per cent of milk produced in the UK will come from dairies no longer shooting male calves. However, the ban doesn’t extend to onward trade and calves sold to dealers can find themselves at the slaughterhouse at less than one-month-old. A 2021 Freedom of Information request confirmed a staggering 65,000 calves were killed in this way during 2020.

For more information on the dairy industry, click here.

Although the UK has welfare standards prohibiting some cruel practices – eg veal crates or calf mutilations beyond a certain age – it doesn’t mean dairy cows live a happy life. Far from it!

Cows would naturally form herds with complex social structures, where daughters stay in the herd and bulls migrate. None of this is possible on a dairy farm and cows are permanently stressed by the unnatural conditions enforced on them.

Most dairy cows have their newborns taken away from them within a few hours or days and spend seven months of each year both pregnant and producing enough milk to feed eight calves. They have been genetically selected to produce huge volumes of milk and this takes a massive toll on their health. That’s why so many of them suffer from serious deficiencies, exhaustion and lameness. And because their udders work so hard, sooner or later most dairy cows develop mastitis – a painful udder infection.

The very basis of animal farming is about minimising costs and maximising profit. Minimising costs comes with minimising movement which means limited or zero grazing where cows spend most or all of their lives indoors. It also means minimising costs when it comes to treatment so as long as cows produce enough milk, they won’t necessarily get the veterinary treatment they need.

Cows simply can’t endure such high physical demands on their bodies for too long and most of them are slaughtered at just over five years of age because they stop being profitable due to infertility, low milk yield or disease.

For more information click here or take a look at what our investigations into the UK dairy industry revealed.

The vast majority of calves raised for veal worldwide are male calves that are by-products of the dairy industry. While banned in the EU, narrow veal crates are still used in the US and many other countries. These tiny wooden crates are so narrow that the calves cannot turn around for most of their lives, depriving them of exercise and preventing normal muscle development – to keep their flesh supple. They are also fed an iron-deficient diet to produce the anaemic ‘white’ veal prized by gourmets.

Veal crates were banned in the EU in 2007 but veal production (in any rearing system) still requires calves to be separated from their mothers within a day or two of birth. These calves are then placed in pens or hutches, alone or with several other calves, before they are sold to be reared mostly as ‘rose veal’.

Rose veal production differs from white veal in that calves may only legally be kept in individual stalls until eight weeks old after which they must be group housed. From birth, calves must be fed a diet that contains sufficient iron to avoid anaemia and from two weeks of age they must be provided with a daily ration of fibrous food to allow normal rumen development (rumen is one of cow’s stomachs). However, feeding the calves a bit better than what constitutes animal abuse is no sign of high welfare and veal calves suffer immensely as they are denied many social and physical needs and are often made to endure weather extremes in their tiny pens. Rose veal calves are slaughtered at around six to eight months of age.

“The best conditions for rearing young calves involve leaving the calf with the mother in a circumstance where the calf can suckle and can subsequently graze and interact with other calves.”

Scientific Veterinary Committee, Animal Welfare Section’s Report on the Welfare of Calves

No dairy calves are allowed to enjoy these conditions.

For more information, click here.

Over the last 40 years, milk yield has more than doubled due to selective breeding and the intensification of herd management. So, whilst the number of UK dairy cows has decreased, the yield per cow has increased by 100 per cent since 1975, up from 4,100 to 8,214 litres in 2021. That works out at 27 litres or 47 pints per day, given that cows generally have an eight-week drying-off period.

The figures above reflect only the average per cow, some cows may produce significantly more (up to 50 litres a day). Either way, it equates to six to ten times more than a cow would naturally produce to feed her calf (4-6 litres) and this takes a toll on her body. It’s the reason why dairy cows always look so skeletal – most of their energy goes into milk production – and they are physically wrecked by the age of five or six. Dairy cows can live for over 20 years, but they are killed at this young age when their productivity falls.

When a cow is suffering from mastitis (a painful bacterial infection of the udder), her body produces large numbers of white blood cells which fight the infection in the udder. Many of these cells, together with dead cells from the inner lining of the udder, then pass out in her milk. The greater the infection, the higher the number of these ‘somatic’ cells (which is another name for pus) in the milk. An increased number of somatic cells indicates infection, so whilst a certain level of somatic cells is considered normal, higher levels mean there’s an inflammation and the udder is shedding more cells than usual – white blood cells, dead cells and bacteria, in other words, the components of what we know as pus.

The average number of ‘somatic cells’ in one millilitre of milk (a fifth of a teaspoonful) in the UK is a little under 200,000. In the UK (and EU), milk with a somatic cell count of up to 400,000 cells per millitre may still be sold for human consumption. That’s two million pus cells in every teaspoonful! Some farmers feed milk that exceeds this threshold to calves.

Around 50 per cent of dairy cows suffer from clinical mastitis every year and 10 to 20 per cent of cows with mastitis are culled as a result. Clinical mastitis produces symptoms such as swollen, hard udders causing a lot of pain to the cow and discoloured or clotted milk.

Antibiotics are routinely used to treat mastitis and may be injected up the teat canal or administered orally. To help decrease the occurrence of mastitis in dairy herds, most farmers practice dry cow therapy. This involves injecting a long-acting antibiotic into all four teats of all cows, whether infected or not, as soon as they enter their dry period (a couple of months before giving birth). There are strict limits on antibiotic residues in milk and milk containing more than the permitted trace amounts is rejected – however, small amounts may be found in milk and the widespread antibiotic use in the dairy (and meat) industry is contributing to the global antibiotic resistance crisis.

For more information, click here.

Cows on organic farms are still impregnated every year to provide a continuous supply of milk and endure the trauma of having their calves taken away within two days of birth. They also carry the dual load of pregnancy and lactation just like cows on conventional farms and male calves suffer the same fate as calves born on non-organic farms.

Organic cows are allowed to graze but, on average, they still spend over five months indoors (in sheds) which severely restricts their movement and natural behaviours. The only way to help animals, protect the environment and your own health, is to avoid dairy. There are plenty of alternatives available.

There are tens of thousands of dairy goats in the UK and most of them are kept in large-scale, intensive, zero-grazing units. In the UK, most farmed goats are confined in massive zero grazing (never going outside) or very limited grazing units. It’s done for the ease of herd management and makes life easier for farmers but is certainly not good for the goats, who are naturally active and inquisitive animals that thrive on hilly or mountainous tough terrain.

The system is the same as for cows – kids are taken away almost immediately after birth, the females replenish the herd and the males are killed at birth or sold for meat.

For more information go to the page on dairy goat farming.

There are 1.9 million dairy cows in the UK. Most give birth to a calf every year and they all have to be fed and the farms need to be maintained using electricity and fuel and vast amounts of water for feed crops. Dairy farming also means continuous emissions of methane (a potent greenhouse gas).

The three main greenhouse gases are carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄) and nitrous oxide (N₂O). Methane is produced in the cow’s stomach as a result of enteric fermentation and from stored manures. Nitrous oxide is produced as a result of soil management and the application of fertiliser and manure. Methane is 27 times more potent than carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide is almost 300 times as potent.

Globally, dairy contributes around 20 per cent of livestock’s total emissions – more than pig meat, poultry and eggs. In the EU, it produces more emissions than beef and in a typical EU diet, accounts for just over a quarter of the carbon footprint, sometimes as much as a third. The dairy industry produces four per cent of global emissions. A significant amount when you consider that over 70 per cent of the world’s population are lactose intolerant and don’t consume dairy.

The carbon footprint of cow’s milk is generally three to four times bigger than that of plant-based milks. To produce one litre of cow’s milk, you need 22 times as much water than for a litre of soya milk and 18 times as much land than for almond milk. Most soya milk producers in Europe use Europe-grown soya – sustainable and good for the environment because soya plants enrich the soil and require less fertiliser than many other crops. Almonds need more water than other food-crops but still less than dairy cows.

Find out more about why plant-based milks are better for the planet here.

Many plant milks are made from crops grown in Europe – soya, oats, almonds or hempseed. As such, these plant milks are always more sustainable and environmentally friendly than animal milks.

A cow has to eat a lot of food to just maintain her body, even more when she’s pregnant and lactating. All dairy farms, even those where cows graze for at least half a year, supplement their diet with high-protein and energy feeds – it’s a must as these cows are made to produce so much milk that they simply have to have concentrated food to be productive. These feeds are often made with imported crops but even if the crops were local – it’s still more environmentally friendly to use them for plant milk rather than use them for animal feed, where only a fraction of the energy and calories for the animal feed is then turned into cow’s milk.

The rush to exploit animals for their milk has seen other species added to the ranks of milking machines. Camel milk was another fad to hit British stores with most coming from the Middle East, where animal welfare may not even meet basic UK standards. The camel dairy farming industry has since grown in Australia and the US and many are now using selective breeding methods to increase milk production and profits. This will only add to the suffering of these animals. Furthermore, camels can’t have babies as frequently as cows – the average gestation period for camels is 13 to 15 months. This means when yields drop, worn-out camels are even more likely to be killed and replaced in order to maintain profits.

Because of its higher fat content, buffalo milk is often used to make rich cheeses like mozzarella, ricotta, feta and halloumi. The situation with buffalo dairy farming is similar to the fate of other animals exploited for their milk. Buffaloes are intensively farmed, often without even their basic needs being met and, like males born to dairy cows, newborn males are deemed to be worthless. Even at what would be considered ‘higher welfare’ farms, they are still impregnated and give birth yearly, have their babies removed – which traumatises both mother and baby – and suffer a host of other welfare issues.

Whether the victims are cows, goats, sheep, camels, buffaloes or any other animal, the dairy industry is relentlessly cruel, tearing mothers and babies apart and causing them immense suffering.

How Dairy Cows Are Farmed and Killed

Cows are highly social and intelligent animals. Find out about their nature, how they are farmed and how they are killed.

How Goats Are Farmed and Killed

We may not associate goats with endurance, incredible agility and toughness but they are quite remarkable animals.