Viva! launched its campaign against ostrich meat in 1996 and Tesco was our first target, being the nation’s largest supplier of this meat.

After a vigorous campaign with Days of Action outside hundreds of stores, on 26 September 1997, Tesco withdraw all ostrich and kangaroo meat.

Somerfield was next, cancelling a whole new range of prepared dishes containing exotic meats.

Booker, Morrisons and Asda gave up without a fight.

Sainsbury’s also conceded.

It just goes to show, exotic meat – just like any other meat – has no place on our supermarket shelves.

Waitrose Supermarkets have dropped the sale of ostrich meat from all its stores.

We planned a Day of Action outside Waitrose. As we were driving to the press call outside their flagship store, they had a dramatic change in policy which was faxed through to Viva! today, Friday 26 February.

Waitrose claim the decision was taken because of ‘supplier difficulties’ but the timing was clearly designed to pre-empt a national media photo call outside the company’s prestigious Finchley Road store. Members of Viva!, dressed in dull grey suits and with sand buckets over their heads, were to carry the slogan – ‘Waitrose management – hiding from ostrich cruelty’. It was to be followed by a national day of action against Waitrose by Viva! groups across Britain on Saturday 27 February. Waitrose conceded defeat just half-an-hour before the press call.

Juliet Gellatley, Viva! Director, says: “This is the final victory for wildlife against the big supermarkets. Tesco, Somerfield, Morrisons, Asda, Sainsbury, Booker Cash & Carry and now Waitrose – one by one they have all dropped ‘exotic’ meats as Viva! has focused public attention on their cruel trade in wild animals. We have no hesitation in claiming Waitrose’s decision as our final victory in this campaign, which has been fought at a local level all over Britain. The vast majority of the general public has been behind us – disgusted by the sale of kangaroo, alligator, crocodile and ostrich meat.”

Viva! launched its campaign against exotic meats three years ago and targeted individual supermarkets one at a time. Tesco was the first – and the biggest supplier. Only days after issuing a press release saying that kangaroo meat was ‘flying off the shelves’ it dropped all exotic meats because of ‘lack of public demand’. Somerfield were next, cancelling a whole new range of prepared dishes containing exotic meats. Booker, Morrisons and Asda gave up without a fight. A national day of action against Sainsbury’s in July 1998 pproved a public relations disaster for the company. A second one was planned for February 1999. Sainsbury’s reluctantly gave in and dropped the meat just days before – because of ‘lack of sales’.

“We have shown that these monolithic organisations are extremely vulnerable to public pressure and we have effectively stopped them from acting as Trojan horses for the exploitation of the world’s disappearing wildlife”. There are clear lessons here for the future and concerns over new possible threats such as genetic modification,” concludes Ms Gellatley.

“Come meet and feed these long legged birds at Winchfield Park Ostrich Farm. The tour will last an hour. Feathers, eggs and meat for sale,” declared the ad in the Hampshire Food Festival’s brochure. A guided tour round an ostrich farm seemed too good an opportunity to miss so we booked our place, turning down the offer of ostrich goulashe for lunch, and set off the next morning.

Viva!’s ‘exotic meat’ campaign covers ostriches, crocodiles and kangaroos – animals who are increasingly being carved up and served for dinner in ‘trendy’ restaurants across the UK. For each species we have produced a fully-referenced report detailing the cruelty involved in farming them, or in the case of kangaroos – ‘harvesting’, to use the industry’s term – and the way they are killed. I knew that a trip round an ostrich farm (even as an invited guest as opposed to undercover as our visits to farms tend to be!) would reveal typical examples of the suffering ostriches endure when kept in the unnatural conditions of a British farm. And sadly, I was proven right.

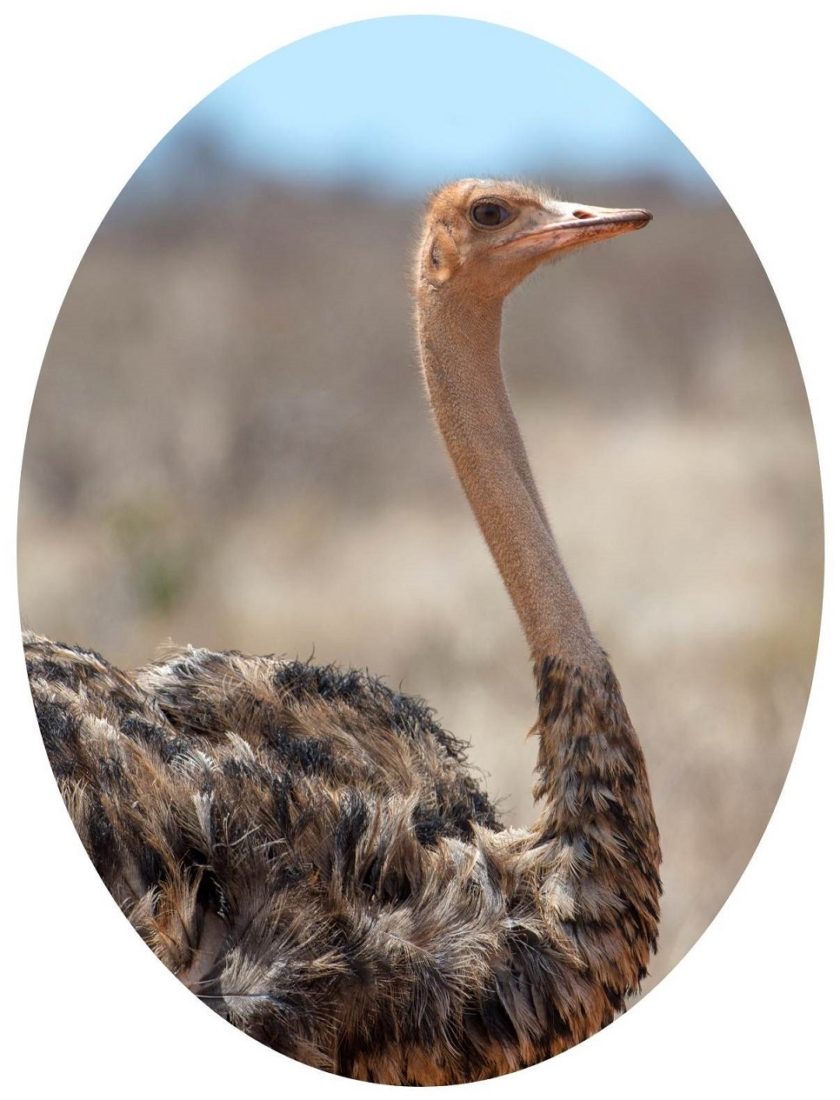

The first thing that struck me was how absurd it was to see these enormous wild birds, who belong on the hot, dry plains of Africa, cooped up in a paddock in Hampshire. They looked totally out of place. And then I noticed that each and every ostrich, without exception, had a huge, featherless patch on their back. I was not the only one to notice – one of the first questions another visitor asked was what cased the baldness.

My mouth dropped open in disbelief as I heard the farm owner’s explanation: “We have to keep them indoors during the winter months and they get a little bit bored, so to amuse themselves they pull each other’s feathers out.” You can just imagine it can’t you, the ostriches grouping together and saying “Come on guys, it’s not much fun in here, let’s pull each other’s feathers out! What a laugh!”

The flippant excuse really upset me – a quote from the trade magazine Ostrich News, and quoted in Viva!’s “Nowhere to Hide” report paints a truer picture: “Dr Judith Samson of the Ratite Management Centre, Canada, says that farmed ostriches show many examples of abnormal behaviour. Feather picking, where a bird aggressively pecks feathers from the back of a pen mate, is again brought about by “stress and boredom”. Dr Samson says: “…it is most severe in winter months because of prolonged confinement”.

The farm owner chatted away merrily, not realising that I worked for Viva!, and although I asked some awkward questions, I decided to keep quiet in order to learn as much about the farm as possible. We were told that each ostrich yields approximately 40kg of meat, and that they are killed between 12 and 18 months of age. In the wild ostriches can live to 70 so just as with other farmed animals, the birds are killed when only babies.

I decided to ask about their slaughter – how and where it was done. According to the American Ostrich Association: “Transportation is dangerous and stressful for both man and beast. Most injuries are related to activities of handling and transport.” DEFRA advice on ostrich slaughter is not specific and amounts to nothing more than ‘non-statutory guidance’, but makes clear that killing ostriches is both difficult and dangerous. I was interested to hear how these ostriches would end their days. I was told that they are killed in a licensed slaughterhouse ‘up North’ and are sent for slaughter five at a time, in a horsebox.

The owner admitted that the long journey was very stressful for the birds and that she would like to find somewhere closer to home, but nowhere was licensed. I asked how the long-legged birds would be able to stand up whilst careering along in a horsebox, but my question was dodged.

Ostriches with bald backs due to feather pecking

We continued our tour round the farm. I saw several birds with wounds on their legs and one ostrich with two huge gashes in her neck. We were told that the birds are sensitive by nature and very easily frightened and that the wounds had been caused by the ostrich running into the paddock fence whilst trying to escape. Because of their timidity, and the fact they are still officially classified as ‘dangerous wild animals’, the farm is not normally open to visitors. I took note of the sign at the entrance alerting us to the danger and who to call in the event of an emergency. Yet another perfect example of why ostrich farming is both cruel and crazy.

Winchfield Park farm does not breed ostriches so no eggs are laid there. The ‘stock’ is brought in from abroad – the owner wouldn’t say from which country – and the chicks live out their short, unhappy lives penned into a paddock or cooped up inside a barn. Chick mortality, we were told, is 50/50 – in other words half the baby birds die.

Come the end of the trip, I once again declined the offer of a bowl of ostrich stew and with no ‘good bye’ headed off back home. That was the Friday, and mid-morning the following Monday, my telephone rang at work. A gentleman had called in asking for the ‘ostrich campaigner’ and had been put through to me. He said he was interested in our ostrich campaign and wanted to know why we ran it, wondering ‘what our problem with ostrich farming was’. Politely, I explained: it’s totally unnatural to keep wild animals like ostriches in a muddy field in the UK, keeping them in captivity is riddled with problems causing the birds physical pain and psychological distress, and the transport and slaughter of the birds is particularly traumatising. I couldn’t prove it, but I was pretty certain it was someone from Winchfield Park ostrich farm on the phone. Perhaps my awkward questions had been noted.

Did you know that ostriches have extraordinary eyesight? Their eyes are 5cm across and have three sets of eyelids, helping them to spot predators from a long distance.